Bussey Bridge Disaster: Feature News Account

By the accident yesterday on the Boston & Providence Railroad thirty-eight souls were buried into eternity and some forty persons were more or less injured. It was by all odds the most serious of any accident of a like nature that has happened in this State for many years. Beside it the Wollaston disaster pales into insignificance.

In point of numbers killed and injured it rivals the White River Junction accident, although the terrible results from fire that followed that catastrophe were happily averted in this instance. And in this event the company is to be complimented for the precaution taken in having the doors of the stoves all locked. By this means the hot coals were kept from falling upon the victims when the terrible crash came. It seems, however, that one stove door – in the smoker, it is thought – was wrenched open and some upholstery ignited, but the incipient flames were quickly subdued.

The dead and the dying were speedily cared for, and very fortunately for the wounded, the police stations were so near that ambulances hastily summoned were soon on the spot and the suffering ones taken to the hospitals, where they were promptly cared for.

Now that the accident has occurred the natural question that arises is, “How did it happen?” Of course, everyone knows that “it was a bridge that gave way,” but no one yesterday seemed to be very clear as to just how and why it happened. Competent civil engineers and others who made investigations yesterday were very emphatic in saying that the material of which the bridge was composed was imperfect.

What these experts say, as well as a detailed list of the killed and wounded and a graphic story of the wreck is appended.

Roster of the dead – Full list of those who perished at “Pussy Willow Bridge”

Of those who were either killed at the accident, or who have since died from their injuries, the names of thirty-eight are known and given below, and this probably includes all up to date. There are two more victims of the accident lying at the point of death at the Massachusetts General Hospital and probably will not survive today. It is also likely that others are so seriously injured that they cannot live long. The following list is the death roll complete up to the time of going to press this morning. Among the names of those known to be killed are the following:

Assistant Conductor Myron Tilden, Dedham

Miss Lizzie Mandeville, Dedham

Miss Lizzie Walton, Dedham

Edward E. Norris, Dedham

Mrs. Kennard, Roslindale

Mrs. Harkins

Patrolman Waldo B. Lailer of Division 13

William S. Strong, Roslindale

William Edward Durham, Roslindale

Miss L.H. Price, Dedham

Miss Barry

Mrs. Hormisdas Cardinal, Roslindale

Alice Burnett, 16 years

Webster Clapp of Central Station

Mrs. Cornell of Washington St, Roslindale

Edgar M. Snow of West Roxbury

William Johnson, violinist, Roslindale

Brakeman Smith of West Roxbury

James Gates of Roslindale

S.S. Houghton, gasfitter, Roslindale

William Snow of West Roxbury

H.F. Johnston of Boston

O. Henry Gay of Centre St., Roxbury

Henry Stone of West Roxbury

Mrs. Sarah E. Ellis of Medfield

Miss Norris, West Roxbury

Webster Drake, Conductor, Dedham

Mr. Adams of Roslindale

- - - - Barrack, Corinth St, Roslindale

Miss Swallow, Roslindale

Miss Ida Adams, 16 years, Roslindale

Rose Walsh, Park St, West Roxbury

Albert S. Johnson, 40 years, Roslindale

Peter Swaben, tailor, 45, Roslindale

Emma O. Hill, Roslindale

Hattie J. Dudley, Roslindale

Mrs. M.L. Odiorne, Dover, N.H. employed on Summer St., Boston

What caused the accident? A Boston Civil Engineer says the material in the bridge was imperfect

Among the earliest arrivals of city people at the scene of the accident were a number of gentlemen who are highly thought of in the scientific world, and some who are well known among the leading civil engineers of Boston. The nearness of the accident to Boston, and its easy accessibility, drew these gentlemen to the spot in order to observe the peculiarities of the bridge and to examine it from a scientific point of view. The state of things they found caused considerable astonishment among them, and there were many things in the construction of the structure which at first seemed somewhat odd, but an explanation of the history of the bridge removed some of the adverse criticism, but it did not – to judge from some of the remarks that were heard – add much to the reputation of the engineers who constructed it.

The facts in regard to the history of the Bussey Bridge, better known as the “Tin Bridge” appear to be about as follows: The original wooden bridge was built a long time ago, and was made wide enough for a double track, but there never has been but one upon it. Very naturally the side on which the track in use was placed gave out first. When it was found that the truss on the northwest side required to be replaced the company took it out and put in an iron truss and left the other side wood as originally built. This was the condition of the bridge for a number of years according to the statement made by a well-known Boston engineer. Thus, one end of the floor beams rested on wood and one end on iron. After a while the company found that it would be necessary to remove the wooden truss, and it was done. The iron truss on the northwest side was moved over on to the position vacated by the wooden truss, and its place was supplied with a new iron one, which was supposed to be stronger than the first iron one. This new iron truss, up to the moment of the accident, carried the greater part of the load that passed over the bridge. This accounted in some degree for the reason of the mechanical experts finding what was very odd to them, that one of these trusses was so different from the other, something of an unusual occurrence.

The facts in regard to the history of the Bussey Bridge, better known as the “Tin Bridge” appear to be about as follows: The original wooden bridge was built a long time ago, and was made wide enough for a double track, but there never has been but one upon it. Very naturally the side on which the track in use was placed gave out first. When it was found that the truss on the northwest side required to be replaced the company took it out and put in an iron truss and left the other side wood as originally built. This was the condition of the bridge for a number of years according to the statement made by a well-known Boston engineer. Thus, one end of the floor beams rested on wood and one end on iron. After a while the company found that it would be necessary to remove the wooden truss, and it was done. The iron truss on the northwest side was moved over on to the position vacated by the wooden truss, and its place was supplied with a new iron one, which was supposed to be stronger than the first iron one. This new iron truss, up to the moment of the accident, carried the greater part of the load that passed over the bridge. This accounted in some degree for the reason of the mechanical experts finding what was very odd to them, that one of these trusses was so different from the other, something of an unusual occurrence.

Among the gentlemen who examined the bridge was Professor George F. Swain, instructor of civil engineering and hydraulics at the Institute of Technology, who succeeded Professor Vose, and who is also a specialist in bridge construction.

Professor Swain was interviewed at his residence on Brookline Street last night, and very courteously stated the result of his observations at the scene of the wreck.

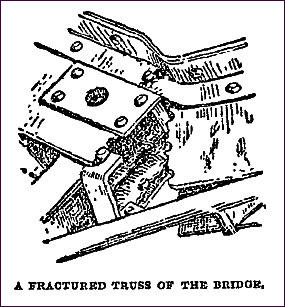

“The bridge,” said he, “was composed of two iron trusses of different patterns, built at different times and by different builders. The floor beams were hung from the top chord of one of the trusses and appeared to rest on the top of the other. The north truss, the one from which the floor beams were hung, had chords built by three ’ I ’ beams and three bent plates forming a closed column, and connected by castings against which these columns abutted. The floor beams, which were of two ’ I ’ beams, were hung from pins run through these castings and the hangers were inaccessible for accurate inspection.

“It is a principle in bridge designing that there should not be any part of the bridge which cannot be examined so that the inspector can satisfy himself that it is in proper condition. On the Erie Railroad their specifications for iron bridges required that the hangers for floor beams shall be easily accessible. The same is true of other important railroads in the country.

“In looking at one of these hangers, where one floor beam was hung at the end joint of the upper chord, I found that the hangers were defective and had been largely rusted off. These hangers were made with a weld, and the weld seemed to be in some places imperfect, and it seemed to me extremely probable that at this joint where the hangers were broken the original rupture might have occurred. The hangers were broken off, and in examining them you could see that one of them was entirely rusted off and the other partially so, the weld being moreover defective. I see by The Evening Globe that it is stated that there were defects of a similar kind in other parts of the bridge.”

“Did you notice any other defects?”

“There seems to be no doubt that the quality of the material was imperfect in some places. Several other portions of the wreck of the bridge showed evidence of faulty design in the trusses. At the time these bridges were built cast iron was used to a considerable extent in connecting parts of the bridges, but engineers have now entirely discarded that material in important structures. I should state, however, that I did not notice any place in the bridge where this material had failed in this case.

“The angle of skew of the bridge was very large. The skew bridge is more difficult to design correctly than a straight one, but it is perfectly easy to make a skew bridge perfectly strong. The fact that it is a skew is no reason for any defect, as I have sometimes heard it stated.

“What I noticed particularly were these two hangers which held one floor beam at the upper end of the sloping end post. These hangers were entirely inaccessible, and inspection could not determine whether they were in proper condition or not. The hanging of the floor beams to the upper chord of a deck bridge is a fault in design and very easily avoided.”

“Do you know whether the Boston & Providence Railroad had this bridge inspected lately?”

“I do not know whether they have any inspector or not, but every railroad company should be obliged by law to have their bridges inspected once a year by a competent expert. The principle may be laid down that if a bridge is so constructed that it cannot be determined whether or not it is in a safe condition - aside from the structural defects in the iron, which may of course exist without our being able to discover – it should be considered as unsafe.”

“Would you say, Professor, that if this bridge had been examined by any competent expert within the past year, these defects would have been discovered and remedied and the accident averted?”

“I think the hangers in that bridge were so inaccessible that it would have been impossible to determine exactly their condition. They might have been unsafe without an inspector being able to detect it. At another joint of the bridge,” continued the Professor, “I noticed that the hangers had a defective weld. That joint was easy to see today, but in the ordinary condition of the bridge it would have been impossible to see the hangers.”

“Would a competent expert have condemned the faulty construction of the bridge that you have spoken of, even if he had not discovered the rusted hangers?”

“Any expert would have been obliged to state that there might have been faults in that bridge which he could not discover. He could not have sworn to the safety of the bridge independent, as I have stated, of the structural defects in iron. He could not have been able to state that the bridge was safe, but he might have discovered it was unsafe in some points, but those hangers he would not probably have been able to examine.”

“How did you come to make this examination?”

“Well, I am interested in any case of failure of a bridge, and I make it a rule to visit cases of this kind, when in reach. In this case I went out with a number of my students.”

“Do you know anything as to the inspection of the bridges by the Boston & Providence Railroad?”

“I will say this, that the railroad had always been well managed, and I know that they have of late years had their bridges built after the very best specifications, and by the very best companies, independent of price. They have evidently intended to put up sound structures, and not cheap ones. I suppose that they have had proper inspection, and, as I have said before, they ought to have had an inspection, and probably did, of this bridge as well as others. Unless a bridge can be proved safe it must be considered as unsafe.”

“Could any reputable engineer have reported that this bridge was safe unless he had been able to examine these hangers?”

“He could not have sworn that it was safe.”

“Would he have been obliged to report that the bridge was faulty in construction?”

“He should have reported that the bridge there is not constructed as bridges were built and that it violated the principle that all parts should be easily accessible.”

“Do you consider that these rusted hangers were the cause of the accident?”

“Well, I do not see how it could have been anything else so far as my investigations determined. I am surprised,” said Professor Swain, in conclusion, “that the Boston & Providence Railroad, which has been so particular in these matters, should have allowed a bridge like the South Street to remain in such a condition.”

Was the bridge inspected? Superintendent Folsom says it was, and was thought to be safe

Conflicting reports as to the safety of the bridge were made by the regular passengers as they came in from the wreck. Many declare that the bridge was known to be unsafe, and it was stated on the street that an engineer had recently made a report to that effect to the railroad.

This is denied at the depot. Colonel Folsom said: “We have a competent engineer in the employ of the company who examines the tracks and bridges several times a year. Bussey Bridge, along with the rest, has been examined recently and no adverse report has reached the officials. For aught the company knew, that bridge was perfectly sound. That it gave way is certain, and this was no doubt the cause of the accident.”

The statement was made last night from good authority that George Folsom, Master Carpenter of the Boston & Providence Railroad, had inspected the bridge within six weeks and reported it to be perfectly safe.

Clerk Crafts of the Board of Railroad Commissioners said yesterday morning that the board had lately recommended to the railroads of the State that inside guardrails be placed within the tracks crossing bridges. It is understood that this recommendation has not been complied with by the Boston & Providence Railroad. It certainly was not as regards this bridge. There were, however, guard timbers upon the bridge. In the case of this particular accident the omission made no difference, as the train did not topple over the side of the bridge, but fell bodily through it, owing to the collapse of the structure.

The commissioners went over the railroad last October when making their annual examination. Nothing amiss was observed at that time. The commissioners who made the trip were Messrs. Kinsley and Stevens. It is understood that the Boston & Providence Railroad has no regular civil engineer, but has a bridge-builder, roadmaster and superintendent, amongst whom are shared the duties which would devolve on a civil engineer.

Story of the smash-up – Pathetic scenes witnessed by those who were early on the scene – The dead and dying.

It is White River Junction over again with all its sickening details of horror and misery. This time, however, it was on the Boston & Providence Railroad. It was the 7 o’clock train from Dedham, with its living freight of workingmen, businessmen and store girls, all rushing along over the rails toward the city.

A train was made up at Dedham consisting of nine passenger coaches and a baggage car. At Roslindale many more got aboard, and the train started up toward the city. Conductor Tilden and Assistant Conductor Drake being busy gathering up the tickets, a great number of them being seasons.

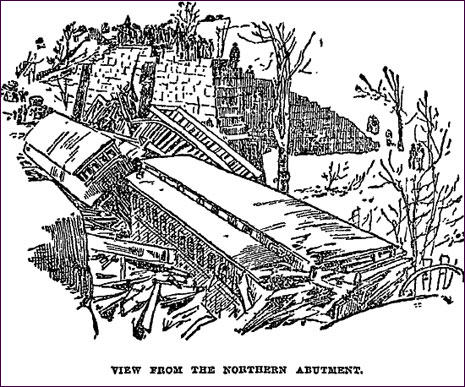

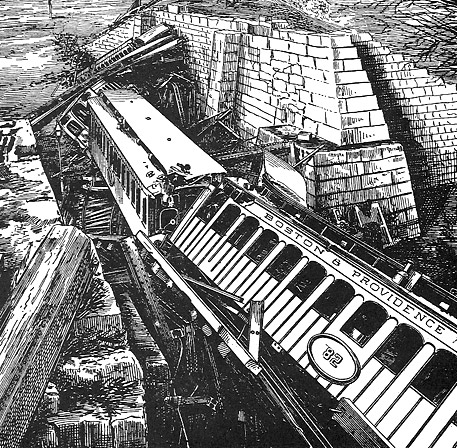

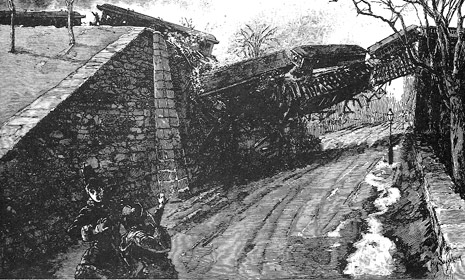

Just this side of the Forest Hills Station is the famous South Street Bridge, which runs obliquely with the track. On either side the track is built high up on an embankment, and meadows covered with snow and ice surround it on either side. The engine and three cars passed safely over the bridge, but when the next car touched the abutment there was a tremor felt, and in an instant the farther end of the bridge gave way and, the third car breaking through, it went down, down, dragging all the remaining cars with it.

The first car was turned completely over, and the one immediately following it broke through it and smashed it into a million splinters. Then came the other cars tumbling one after another into the street below, a distance of fifty feet at least.

Those in the forward car who went down never lived to know what had happened. They were mangled and squeezed up in horrible shape. The other cars were terribly mixed up with sleepers, rails, heaters, etc.

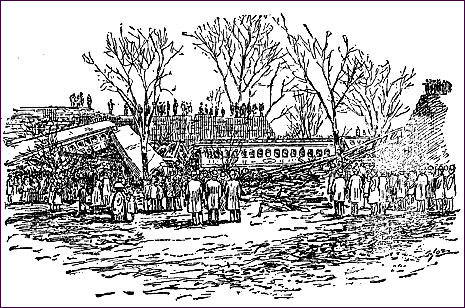

The distance from one abutment to the other is some 150 feet or more, and every particle of bridge was carried away. Immediately the rear cars broke away and fell through. The Engineer, with great presence of mind pulled out the throttle valve of his locomotive, and putting on full steam dashed to Forest Hills, and jumping from his engine rushed to the nearest fire-alarm box and pulled in an alarm. He had seen the cars go down, and knowing the awful history of accidents followed by fire, he was determined to save as many unfortunates as possible.

In a very few minutes after the alarm had been given the fire department was on the scene, but fortunately no fire had broken out.

As a matter of fact, the stoves were pitched about in all directions, and how fire was averted it is impossible to conjecture.

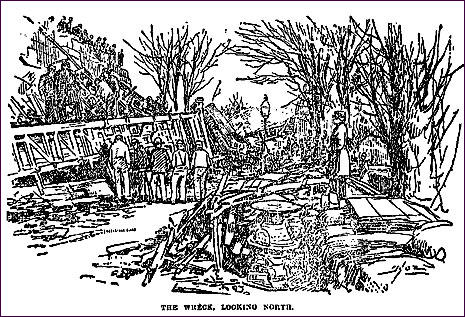

Such a sight as met the gaze of the first arrivals can better be imagined than described. Broken cars, broken rails, twisted bars of iron, and badly mangled dead and dying were all mixed up together.

The car that first went through of course fared worse than any of the others, because it fell with full force to the hard street beneath, and to add to the horror of the situation turned completely over. Imagine, if you can, what would be left of it intact after such a catastrophe. Many men were hurled out of the broken and mutilated windows before the next car was upon it. They have dislocated spines and broken limbs; their heads and faces are cut and bruised and lacerated, but they are yet alive, and may survive.

Although their fate was a terrible one, they still have cause to thank their lucky stars that it was not worse. Very few of those who were not disentangled from the debris by the shock lived to know what happened.

It is supposed that the greater number were killed by the cars falling into each other, rather than by the force of the fall itself.

The last three cars that went through remained fastened together, and with the railroad track, remained in an inclined position looking like a ladder and so wedged together that one could walk from the street below to the top of the stone wall that had served as an abutment to the bridge, along the sides and roofs of the cars.

When the accident took place, those who were in those suspended cars, and who had the strength to do so, crawled out through the windows, and amid the din of the crash and the breaking and creaking of timbers made still more intensified by the wail of the dying and the screeching of those more frightened than injured, they found their way on hands and knees to the street below or to the top of the high stone wall above.

In the two cars on the ground those who were wedged in between seats were taken out, and together with those who were already dead they were laid out on temporarily constructed cots. Those who were able to speak told their names, but many were there who could not articulate a syllable. These were the dead and dying.

Soon the news of the terrible fatality reached the surrounding country, and people, friends of those who were known to have been on the train came flying to the scene. Loving mothers bent over the prostrate forms of dear ones who had left them only a half hour before in perfect health.

Over the body of one young girl who was dead, the police were bending, endeavoring to ascertain her name or where she belonged. There was nothing about her to indicate who or what she was, except that she probably was a store girl, for in her hand she still held a bag that contained her lunch. Her head and body were terribly bruised, and it was evident that she had been killed instantly. A young man whose leg was completely crushed lay beside her, and while some were bending over him endeavoring to soothe his suffering until the arrival of the physicians, he opened his eyes, and, seeing the young girl, he begged those about him to turn their attention to her; that he was strong and could wait until she had been cared for. He was not, however, as strong as he supposed he was, and soon swooned away. He was, however, strong enough to know how to be brave.

The timely arrival of the police and fire department was instrumental in saving the lives of many who were wounded, and as rapidly as possible they were gathered up and taken in the police ambulance to the City Hospital and to the engine house at Jamaica Plain.

What the real cause of the accident was no one even now ventures to conjecture. Rumor has it that a weakened span about the center of the bridge succumbed to the immense strain of the 300 or more souls in the rushing train, and giving way, precipitated the living freight into the abyss below.

This is the only plausible reason that can be given for the calamity, which is particularly unfortunate now, since it was intended to build a double track at this point in the spring, which would do away practically with the bridge.

Another theory advanced by a passenger who was in a position to witness the first phase of the accident, who says that the rear truck of the first car that went down broke and ripped up the trestlework of the bridge, which precipitated the following cars.

This accident is the only one of any serious nature which has happened on the Boston & Providence Railroad, but it is one of the most cruelly fatal in the annals of steam railroading in the country.

When Engineer Walter White of Dedham sent a message of the calamity to the city, a wrecking train was dispatched to the bridge, under the charge of Master Mechanic George Richards, and within an hour Railroad Commissioner Crocker was on the scene examining the wreck and attempting to form an opinion on its cause. The duty was a hard one, and its success doubtful, for with a top of an entire car on the bank above, and its body wedged between two splintered cars below, the task of explaining those conditions was extremely difficult.

It was thought that there was no conflagration in the train at the time of the disaster, but it seems that the stove in the forward car, in tipping over, set fire to the seats and woodwork, though the timely arrival of the chemical engine rapidly subdued the flames, and thus prevented any further calamity.

When the shriek of the engine on the ill-fated train approached the Forest Hills Station on its way of warning, it heralded a horrible and terrifying cry for succor and assistance that will long ring in the ears of those who were destined to be within its reach. With the down-crashing of the train, went up cries that seemed as though of one voice, spontaneous and most heartrending. They were heard far above the din of smashing timbers, crashing cars and breaking glass, and then a silence almost as ominous as was the preceding terror succeeded, only to be again followed by the groans of the dying and wounded, which could be heard for a mile along the railroad. When the first intimation of disaster was received at Forest Hills, J.H. Lennon, a fish dealer living in the vicinity, was harnessing his team, and he immediately started for the wreck. He was the first man on the scene after the accident, and without a moment’s hesitation went to work to rescue the imprisoned passengers.

Shortly after, James McLaren, a florist, employed on Washington Street, also near the wreck, and J.H. Cronin arrived, and the three men did most humane work. In one of the forward cars, and among the first passengers to be taken out, was a young woman named Hattie Dudley, and whose death; for she was killed outright and terribly mutilated as well, was the most shocking of any of the passengers.

When ingress was obtained through the smashed car, and when the splintered timbers had been sufficiently removed to allow of any work upon the wreck, about the first body reached was that of this unfortunate woman, who was pinned down in the car with the face jammed between two sills and in a most shocking condition. That she was alive seemed doubtful, still, the body was moved, when, to the terror of her rescuers, it was found that the head and one arm were severed from the body as though done by a knife. Covered with the rubbish of the wreck, as she lay there, no possible identification of the remains could be made, and after fruitless attempts to remove her with their hands the rescuers obtained saws and jackscrews, and after much difficult work succeeded in extricating all that remained of the woman, who but a moment before was full of life and hope and ambition.

The body was first removed, then the mutilated and unrecognizable head, and finally the arm. Tenderly the remains were covered, and soon after removed to Forest Hills, and later taken to the city morgue.

It would seem from the position of the woman and the circumstances of her death, that the car in falling inward struck her down, the sharp knife like edge finding the neck and severing the head instantly, while some other portion, equally as sharp, did similar terrible work on the arm.

Then, near the stove and lying almost in each other’s arms were two other young women, both dead – evidently instantly killed, their heads crushed also beyond recognition. They also lay wedged in between the debris of the wreck, pinned down so tightly that action was impossible; and here again it required jackscrew, levers and saws to extricate the remains. One woman, who suffered only, and miraculously enough, from slight injury to her feet, was removed from this impromptu coffin and carried home.

Another woman lay cramped between two car seats, with life extinct. Not a mark appeared upon her body to indicate how death approached. Extended with arms pushed forward, as though endeavoring to ward off the crashing timbers which fell about but did not touch her, she lay there as calm-appearing as though in sleep. But the awful position in which the body lay, left no doubt but that in the upheaval of the overturning car, the woman became wedged between the seats and her young life slowly crushed from the frail body. It was an awful sight.

There was death visible in every form. The shapes it took might make a study for the thinker. For with the woman here, apparently so calmly meeting death, right at her elbow was another less fortunate who, while killed, must have suffered terrible agony before death relieved her.

The majority of the passengers in the cars which plunged to death were women. All young, happy, hopeful creatures, whose tiny satchels with carefully prepared lunches, told pathetically, as no words possibly can the circumstances of their daily lives.

Ben Goldsmith, a resident of West Roxbury, was one of the fortunate passengers. He was in the last car to land safely on the further side of the bridge, and, as the car which followed his plunged backward and down into eternity, he jumped through the rear of the car and landed upon the embankment, safe, as the dying cries were sent up from the commingled and indistinguishable mass below.

That the disaster was not even more frightful – that the entire train was not pulled down by the rear cars – is considered due to the fact that directly where the three cars stopped a lot of rails caught them, strangely enough, and holding them, prevented their slipping back.

It was indeed miraculous, for with the first cars sinking, the engine and tender must have followed and the mass of wreckage must have been transferred into a charnel house, where the dead would have been incinerated before they could be removed, and where the terror of fire would add to the torture of the suffering and dying passengers.

Among the many pathetic scenes was that occasioned by the removal of E.J. Norris, a passenger who was among the most seriously injured. He was removed from the wreckage of the train, and taken to a shoe store in Roslindale where he died shortly after. He was carefully removed from the settee on which he lay and borne by his aged father and friends to a common grocery wagon in which he was taken home to Dedham. The deceased was a young man, and highly respected.

Then surrounding the wreck and forcing the lines as much as the numerous lines of police would admit, were men and women, fathers and mothers, brothers and sisters, eagerly seeking news of relatives or friends, and the heart-rending cries that followed the identification of some mutilated body made more than one hardy man weep.

Many young ladies, friends of Miss Mandeville of Dedham, were early at the wreck, doing what little they could to relieve the sufferings of the injured. Their friend was killed.

Among the effects found in the debris was a letter which J.F. Emmons of The Globe picked up in one of the wrecked cars, wedged between broken timbers, and addressed in a bold, masculine hand to “Frank E. Alden, 16 Stevenson’s Building, Pittsburgh, Penn.” It lay beside a little black hand satchel, such as young girls carry their noonday meal, but to whom it belonged has not yet been ascertained.

With the news of the wreck, there was one grand exodus from the city. Every train brought car after carload of the curious. Each train was doubled in length and even then there was hardly room for the travelers; while from Forest Hills to the wreck there was one continuous stream of pedestrians coming and going.

At the wreck the relic-seekers were in force, and the stream of people that turned homeward must have carried with it the major portion of one of the cars. About the ground in the neighborhood of the disaster there were great tracts of land cleared away, and here were piled such railroad effects as had not been materially damaged.

Frank A. Hewins of Lagrange Street, West Roxbury, who was reported killed, has turned up safe. He was not a passenger on the fated train, another man having been identified for him.

Immediately upon receipt of the news of the accident a number of physicians who reside in Park Square, directly opposite the Providence Depot, took the train for the scene of the disaster, and rendered all the assistance in their power.

At the morgue – Description of the bodies found at the dreary abode of the dead

The North and South End Morgues and the City and Massachusetts General hospitals, to which a number of the dead and wounded were taken, were visited by thousands of men and women yesterday. Some were in search of relatives and friends, while the others were endeavoring to learn something about the awful disaster. Among the first of the passengers on the ill-fated train brought to the City Hospital was William Strong. He was unconscious and suffering from a fractured skull and thigh, and severe internal injuries. When laid on the table of the accident room several of the hospital surgeons did all in their power to alleviate his sufferings, but he died within ten minutes after reaching the institution. His body was being removed to the morgue, when another ambulance, in which was Edward F. Durham, drove up to the door. He was also unconscious, his skull fractured, arm badly crushed, and his face was considerably bruised. He was quickly taken into the accident room, where he died in five minutes after his arrival. His body was then taken to the morgue and laid on the marble table beside that of Strong.

The keeper of the morgue had hardly locked the door of that dreary apartment, when the bodies of four men and two women arrived. One of the women was later identified by a gold ring that was on her finger as that of Emma Hill. Her skull was fractured and her face was crushed beyond recognition. The other woman, who was identified as Hattie J. Dudley, had both arms and the left leg below the ankle cut off. Her head was also badly crushed. The bodies of the men were identified as that of Conductor Tilden, Harry Gay, Albert Johnson and Peter Swaben. Their skulls were fractured and Tilden’s ankle and knee were broken and his right thigh badly lacerated. All the bodies have been removed by relatives and friends.

At the North Grove Street Morgue there were four bodies (all women) received. Soon after their arrival an elderly gentleman forced his way through the crowd that stood in front of the place, and on reaching the front door he informed the officer on duty that he was looking for his daughter whom he was sure had been aboard the ill-fated train. On being admitted he looked at each body intently for a minute or two, and on reaching the slab on which the last body laid he took one look at the badly disfigured form, then turned to Superintendent Briggs and said, “That is my daughter Lizzie.”

Her name was Price and she lived in Brookline with her parents. She was crushed about the body, her skull and lower jaw were fractured, and her face was badly cut and covered with blood and mud. Her body was removed to her late home an hour after identification.

Another one of the bodies was identified as that of Lizzie Walton by means of a railroad ticket found in her dress pocket. Her body was considerably crushed, skull and lower jaw were fractured, and her face was badly cut. The next identified was that of Mrs. Sarah E. Ellis of Medfield. She had been spending the winter with relatives at Dedham, and was returning home when she met her death. Like the last two, her skull and lower jaw were fractured, her body was badly crushed and her face was cut in several places. The other body was identified last evening as that of Mrs. Rose Walsh of Park Street, West Roxbury. Her skull and lower jaw were broken, and her head and face badly cut. All the bodies were removed by relatives and friends.

At the hospitals – Webster Drake and George A. Lord in a very critical condition

All the patients at the City and Massachusetts General Hospitals, with the exception of Webster Drake and George A. Lord, who are at the latter institution, were reported to be in comfortable condition last night. Drake, who was the Assistant Conductor of the wrecked train, has a probable fracture of the skull, and is suffering from severe internal injuries. The physicians have but little hope of his recovery.

Lord received internal injuries and his collarbone and right ankle are fractured. He was reported to be in critical condition late last night, and the doctors think there is a slight hope for his recovery.

Late yesterday afternoon, Augustine Drisko, 40 years old, a carpenter, living on Tremont Avenue, West Roxbury, was brought to the Massachusetts General. His thigh was fractured, and he received injuries to his head.

W.S. Jordan, O.S. Hammond, Edward Chapin and Charles N. Schrano, who were taken to the Massachusetts General yesterday morning, returned to their homes when their wounds, which were slight, were dressed. John H. Drayton, Augustine Drisko, Webster Drake, W.F. Bowman and George Lord are still at this institution.

Of the five wounded at the City Hospital, George May and Winfield S. Smith are worst injured. The former has a crushed arm and the latter’s thigh is fractured. They, as well as the other three, will recover.

James H. Noon, who was brought to the institution suffering from a scalp wound, went home after having his injury attended to.

Stories of the survivors – What Engineer White says of the terrible calamity – The other survivors

Many stories, graphic and pathetic, have been told by the survivors of the terrible accident, and among them none are more thrilling than that told by Engineer White, which is appended: Walter Earle White, the Engineer on the fated train, to whose cool head and thoughtful action the safety of many a life may be attributed, is one of the oldest and most reliable employees of the Providence Railroad. When less than 18 years old he obtained employment with the corporation, and with the exception of two years when he acted as fireman, he has been an active engineer and constantly employed on the branch railroads of the Dedham Division.

Mr. White is about 52 years old, though looking much younger. He is somewhat tall, of robust figure, and a whiteness of hair that seems to belie his age. Sparsely as his hair grows upon the crown of the head, it is thick and luxuriant in the “mutton chops” which adorn his face, and while both are white almost to veneration, there is a tinge of black in the beard, which gives to his countenance at least some resemblance to youthfulness. A florid complexion sets off the white hair and beard, and the robust and active figure give but little indication of the almost threescore years through which his life has passed. When seen last night in his cozy home in Dedham he was just recovering from the effects of the direful calamity which will forever mark the history of that little town.

Directly across the road – not a dozen yards from Mr. White’s home – was the Mandeville cottage, where poor Lizzie C. Mandeville lay cold and still in death; while barely more than three blocks away, lay Lizzie Walton, an employee of Jordan Marsh & Co., the only two Dedham girls who were killed. Both were young girls, the oldest certainly not over 18 years of age, and both were loved and respected by the large circle of acquaintances to whom they had endeared themselves by their good nature and geniality.

Engineer White was most willing to tell his experience during the terrible moments which elapsed between the passage of his engine over the rotten bridge and the time of succor and relief, and according to his statements the cause of the accident is still as remote as ever. “It may have been a broken rail,” he said, “perhaps a broken journal or a broken car wheel,” but even these would not account satisfactorily for the sudden breaking of the iron girders, which, as they lay there in the middle of the road, broken and twisted, showed the worn and rusted interior which nothing but the frequent coatings of paint kept hidden from external view.

“We were the 7 o’clock inward train from Dedham,” said Engineer White, “due to leave Dedham on the hour of 7. Monday is always a heavy day, and our freight being principally young women employees, the company a short while ago added another car to the train, making this early train one of nine cars instead of eight as it is on the remaining days in the year. However, we started on time from Dedham, though owing to the length of the train, we may have been some minutes late at the subsequent stations.

“At Roslindale we received a large fare as well as at the intermediate stations, and from here we started for Forest Hills. As we approached Tin Bridge there was no appearance whatever of danger. The bridge lay as solid and safe as ever, the span across showing no weakness, and gradually the train approached. The engine and tender had passed when I looked backward at the cars behind me. What the cause of the glance was I can never explain.

“I was urged to from some unseen source, and then again I was not. One looks more naturally forward than behind, and at this juncture particularly the look may have been suggestive. However, as I cast a glance at the train behind, I saw the first car swing inward and topple over as though about to fall, and while I still looked, amazed and bewildered, the second and the third cars tipped over in similar positions and all finally jumped the track. The engine kept to the rails, however, and I turned for a moment to slack my engine. When I looked back, and the time consumed was a very brief minute, of the nine cars but three remained in sight, and the cloud of dust which rose prophetic over the bridge told to a certainty the fate of the remainder.

“No, I heard no shriek, I waited for none, for when I saw what fatality had befallen us, I made instant start for relief. With the concussion of the shock, or of the cars leaving the track, the coupling pin attaching the engine to the first car snapped and we were free. With all the steam on and with the throttle wide open we started for relief.

“Forest Hills was the nearest station, and to this point we started. Our whistle was screaming the most terrifying of screeches, seemingly conveying to the listeners the direfulness of the calamity which had befallen us, and all the while the fireman was signaling with his hand to the people in the vicinity of the wreck, and endeavoring to thus explain the casualty. Explanation was not needed. What could the inference possibly be, from a single engine rushing madly along the track shrieking, as though trying to tell in words the danger its freight had met? There were no cars, not even a baggage car, and where was once a bridge there still arose a dense, horrible dust, which enveloped the surroundings and forbade all sight of the disastrous spot.

“We kept on, and immediately the neighbors divined our signals and rushed to the bridge.

“This was about 7:19 o’clock, the time we were due at this point, and the time consumed in making the trip from the bridge to the Hills was briefer than the time it takes in telling it.

“Still on we went. We passed Switchman William Wordley, ‘For God’s Sake,’ I cried, ‘shift the switches and let him go,’ and onward we rushed until at length we reached Forest Hills.

“There Jim Prince was waiting for me. Jim goes out of Dedham about an hour ahead of me, and meets me ordinarily between Jamaica Plain and the Hills. This morning, however, being a trifle late, he reached the Hills without meeting me, and as briefly as possible I told him the circumstances of the disaster, and begged him to give the passengers what succor he could.

“Prince’s train comprised but three cars, the majority of his passengers being laboring men, sturdy, stout fellows, who would work nobly for the lives of the imprisoned ones.

“Jim at once put on steam and started up the branch track. In the meantime there were scores of workers on the spot to help us. Woodcutters, way off in the distance, hearing our whistle screaming started for us. Willing hands in the vicinity added their strength to the combined energy, and the work of relief began at once. Physicians came to give relief, and succor seemed to pour in upon us from all sides, yet I knew nothing of it. Reaching Forest Hills I went directly to the Station Agent, and told him to telephone for doctors and ambulances, and this matter settled, I steamed back behind Jim Prince’s train and here we banked the engines, made the valves safe and set to work to rescue the passengers. All this work consumed perhaps ten minutes, and when we left our engine a hundred willing hands were ahead of us. I could do no work whatever. What little strength I had deserted me, and all I could do was to look upon that mass of crushed timbers below, and in a dazed way picture what might have happened had the engine, with its roaring fires, tumbled upon that pile of debris.

“My fireman, however, Albert Billings, did noble work. Billings has been with me some four years, and I knew him to be a worthy helper, one to be depended on, and down into that indistinguishable mass he went, and worked as though he were the least disinterested man in that entire party.

“The work these men did was marvelous and in less than forty minutes at the farthest from the time the bridge gave way, every dead and injured body had been removed, the last ones perhaps being Miss Mandeville and Miss Walton.

“I could no more have run an engine today than I could have accomplished any impossibility. Weak as a child and practically useless still with the strain, who could wonder?

“What was the cause of the disaster? I don’t know a thing about it more than you, save what I have told you – perhaps a broken journal, a rail or a wheel. The Providence Railroad takes excellent care of its tracks, and branches and main lines alike receive strict attention.

“How long before travel will be resumed? Perhaps in two days. Yes, by Wednesday, I have no doubt, girders will be placed across the embankments and trains will be again running.”

Mr. Pike’s experience – He was a passenger on the smoking car – How the accident occurred

About 10 o’clock a Globe reporter met Mr. Pike of Roslindale on Boylston Street, and from him learned the following particulars of the mishap.

“I live at Roslindale,” said he, “and make a practice of taking the early train for Boston every morning. This morning the train, consisting of seven passenger cars, a smoker and baggage car combined, and an engine, left the little station at Roslindale at 7:15 o’clock.

“As is my custom when going into Boston, I jumped into the smoking car and was fortunate in getting a seat among the baggage. I think there were probably thirty men in the compartment where I was sitting. Several of them were baggage handlers and employees.

“About half were sitting down, and the remainder were standing or leaning against the sides of the car. Nearly all of us were smoking, and talking about the news of the day, or wondering what the coming week had in store for us.

“I knew that not one of us was dreaming of the news that we were to make before the end of ten minutes.

“The old Tin Bridge, or ‘Pussy Willow Bridge,’ as it is sometimes called, is about half way between Roslindale and Forest Hills. It spans a stream which runs between the two banks and crosses from shore to shore at a height of, I should say, about forty feet. I have crossed it hundreds of times, and had no more apprehensions as to its safety than I do of the stairway which takes me up to my bedchamber every night.

“My pipe was going in good shape. The morning air was clear and cool, and I was enjoying myself as best I knew how. I don’t know as I ever felt better in my life, or more secure from harm.

“Just as we reached the bridge I felt a rocking, grating sound, as if someone was suddenly putting on brakes. It was not only a sound, but a tremor, which swayed the car in which I was sitting from side to side; the way a train will swing when it is going around a sharp curve at a rapid rate. Please remember that I was about midway in the last eight cars, so I could feel and hear those ahead of me crack and grind for a second or more before I suspected that anything unusual had occurred.

“All at once I was aware that the car in which I was sitting was tipping over to the left; actually going over in that great deep hole below. At first, I imagined that I was fainting away, and the tipping sensation was due to giddiness. I had presence of mind enough to catch hold of the wooden cleats which are nailed to the studding of the baggage car, and then over she went.

“Baggage was rolling and skipping around the car; men were jumping and holding on trying to keep their feet; some throwing their pipes away, others making for the door, and still others rolling and jumping around as best they could to keep away from the trunks and boxes which were everywhere at once.

“There was no jar when the car fell. The car tipped over to the left; fell without meeting any obstruction, and brought up with a crash, bottom side up. It jarred me terribly, but I managed to keep my grip, and still held my balance until the car ceased to crash and sway.

“Then I let go my hold, got on my feet, and limped out through the big baggage door to look around and see what had happened. It was not a pleasant sight that met my eyes.

“The engine and the three head cars were still on the track. In the deep ditch, some on their ends, some on their sides, some bottom up, most of them smashed and broken, and all more or less injured were the five rear cars, strung along in the order in which they had come from Roslindale. The car I was in was bottom side up. Its roof was broken in, and all the glass was smashed.

“I heard the people in the cars crying and yelling for help. I saw a black line of people with torn clothing, and here and there a broken arm or bleeding face, come pouring out from doors and windows; in short, I saw all the attendants of a big railroad disaster, save the fire.

“Then I went to work. I got a stick and broke out the sash in our car and began to help the people escape. They acted very gallantly. Many were badly scratched and hurt, and some had broken limbs, but except when some unfortunate was pinned down there was very little loud crying. There were many women in the cars, shop girls, milliners and clerks, and they were fully as brave as the men. I did not think people could act as well as they did.

“I worked there for perhaps an hour, and in that time I saw fifteen dead bodies taken from the cars, while ten or a dozen were carried away badly injured. Of those who were hurt, I can give no estimate. There were probably 300 on the train, and I doubt if fifty of those in the five rear cars escaped without injury. I think I was as lucky as anybody, and I am not yet over the effects of the jar. My legs are both sore, and my arms are lame. I was very lucky to get off as well as I did.

“Before we had been at work fifteen minutes the police had been notified, and in a very short time ambulances arrived. There were also many private carriages furnished, so that as fast as the injured were taken out they were carried away for treatment. Everybody was as kind as possible.”

Albert H. Chapman’s story – He saw thirteen bodies taken from the wreck – Work of the Police Department

Mr. Albert H. Chapman of Jamaica Plain, Superintendent of the New England Telephone and Telegraph Company, first heard of the accident as he was leaving his town to take the train for Boston at 7:30 o’clock. He went immediately to the scene of the accident, at the overhead bridge on South Street, about 100 rods beyond Forest Hills Station. He spoke as follows concerning the accident: “Three cars remained over the track that went over the bridge, from two of which the trucks had broken off and rolled down the embankment. The engine had been detached and had gone to Boston for assistance. On approaching nearer I found that five cars were lying in the roadway under the bridge. The rear car, the smoker, had turned completely over, and was lying on its top. Two of the cars were destroyed and fit only for kindling wood. The other two were piled up in a heap, one on top of the other. The bridge itself was completely gone, not a vestige of it being visible but the abutments.

“One of the railroad tracks that went over the bridge was bent over like an ox-bow, and lay at the side of the embankment. The iron trestlework of the bridge was mixed up with the wreck of the cars. I should judge that I arrived about fifteen minutes after the accident had happened. I found the members of Engine 28, Jamaica Plain, at work when I arrived. They were clearing away the wreck and taking out bodies. Captain Vinal of Station 13 was at hand with a force of police, rendering all necessary assistance. There were very few cries heard emanating from the wreck. All that were audible were the moans of the wounded and dying.

“I saw in all thirteen bodies taken out, seven women and six men, and they were all dead. I saw several wounded carried away. Some got out of the wreck themselves, and some were helped out. Drs. Stedman, Gerry and Tompkins of Jamaica Plain and Dr. Goddard of Boston were on the spot at 9 o’clock, when I left for the city, caring for the sufferers.”

The police ambulance from Station 4 was telephoned for. Before it arrived the bodies were taken away in carriages and wagons, and mattresses were provided without stint. The residents did everything in their power to alleviate the sufferings. The Sturtevant Blower people furnished all their teams.

Miraculous escape – Mr. Whittemore’s fearful experience in the accident

W.E. Whittemore was seen by a Globe representative at his residence on Florence Street last evening. He said: “I took the early train for Boston and occupied the fourth seat in the fourth car from the engine, the car that was literally smashed to pieces. The first sensation I experienced was that of suffocation, and it appeared to me that the sides of the car were coming together, while the top of the car was sinking. Almost the next instant I found myself lying on my right side with my right hand pinioned between the side of the car and the stonework on which one end of the bridge had rested. My feet were also tightly fastened but I succeeded in extricating them by removing my rubbers. In doing so I badly lacerated my right hand.

“Joseph Metcalf occupied the seat with me and he came out of the accident with two ribs broken and a bad cut over one of his eyes. On the seat opposite the one that I occupied were Mr. and Mrs. H. Cardinal, who live on Washington Street. Mrs. Cardinal met almost an instant death, and Mr. Cardinal was seriously injured about the head. I think I must have been either the fourth or fifth person to get out of the debris, and for at least two minutes could scarcely see anything because of the dust and soot that arose from the wreck. My first impression was that fire had broken out and that the terrible accident that occurred at Hartford, Vermont, was to be repeated.

Although I heard no cries for help, there was crying and moaning by what seemed to me to be nearly a hundred people. I was too badly injured and confused to be of much assistance, but I succeeded, by considerable exertion, in walking home, nearly half a mile distant.”

Statement of Charles Schiano – He got out of the car by crawling through an opening in the bottom

Charles M. Schiano, a barber, who lives in Roslindale, but is employed at the shop of Gottlieb Sessler, at No. 16 Water Street, in this city, was in the rear car, which was a baggage and smoking car. He took the train at Roslindale at 7:15, and the accident happened three or four minutes later. He was aware, from the motion of the car, that something was wrong, and had risen from his seat to make his way out when the car went over and struck bottom side up. He found himself shut in behind the door, and tried to break a window, but failed. He made his way out, however, through an opening which had been made in the bottom of the car when it struck. As he got out he saw a policeman who lay by the car, dying, and whose body was covered a moment later by a brakeman.

Mr. Schiano was badly hurt about the forehead and top of the head by the fall, and was a good deal shaken up besides. He had his wounds dressed at the Massachusetts General Hospital, when he was ordered to go home and keep quiet until tomorrow, and then report at the hospital for further treatment. There were three passengers and a brakeman in the car in which he went down, all of whom, he thinks, were saved.

He says that two of the cars, probably the third and fourth in the train, were crushed to splinters in the shock of the collision, and thinks that few of those in them could have escaped alive. He saw about twelve persons taken out, some dead and some injured. He did not remain long about the wreck, being anxious to get home and inform his wife of his safety.

Gottlieb Sessler, his employer, also resident at Roslindale, was also on the train. He was bruised about the head and stunned, but soon recovered consciousness. Mr. Schiano does not know how serious his injuries were.

Earnshaw’s experience – Helping the wounded after his most miraculous escape

Mr. C.W. Earnshaw, who is Superintendent of Jordan Marsh & Co.’s clerks, was found in his office by a Globe reporter yesterday afternoon, surrounded by a host of friends eager to extend their congratulations for his providential escape from the railroad disaster. His escape was certainly most miraculous. He was one of the few in that fated last car of the train who escaped uninjured.

In relating the details of his narrow escape, he said: “I was seated in the rear car pleasantly conversing with a friend. The first intimation that I had of anything being wrong was a sudden check in the forward motion of the car. It was not a shock but rather as though the wheels were suddenly reversed. This sudden check almost threw me from my seat, and before I could recover myself there came a second jar of the same nature, followed by a third.

“For a moment the car was motionless. I immediately arose and started to walk to the door and out upon the platform, thinking that something must have happened, but never dreaming of the horror which was to come. I had scarcely advanced a foot towards the door when there came an awful crash. Just what had happened I knew not, nor, indeed, did I have reason to speculate upon the state of affairs, for so sudden was the crash that I was dazed and scarcely knew what followed. My head seemed to whirl around, and I felt fearfully dizzy, but I do not think I lost my senses, even though I had such a faint idea of what was happening. I had no idea that the car had turned over, and how it could have done so and that I still remain alive is a mystery.

“My head was bruised, but beyond that I think that I was hurt but little. I was conscious all the time of the crashing of timbers and the most fearful shrieks all about me. After the car had fallen to the road beneath the bridge it was, of course, motionless. As soon as I understood that the worst was over I tried to move myself about, and after a time managed to crawl across the roof of the car, which was now the floor, to a window which was providentially close at hand. All the glass was broken out of the window and with little difficulty I managed to crawl through it onto the road outside. Then for the first time I appreciated the full horror of the catastrophe. I never saw such a terrible sight in all my life, and I trust that I shall never again.

“People were being hauled out by scores from beneath the crushed timbers of the cars; some silent in death, and others shrieking in their agony. I tried to do what I could in assisting those more unfortunate than myself, but soon found that I was so badly shaken up and bruised as to be of little assistance.

“J.H.C. Kendall of Bliss, Fabyan & Co., was seated beside me in the car before the accident. I understand that it is reported that he was killed, but this can scarcely be so, because I saw him after I got out of the car. I know not how badly he was hurt.”

William Young’s explanation – Jammed in between the cars – Women in his car who were killed.

William Young of Roslindale was in the third car from the last of the train that fell through the bridge on the Boston & Providence Railroad. He said that he was seated on the rear seat, and felt the car lunge sideways; then it went down with a crash, the next car following. I stooped down as the roof of my car came down with a crash, just clearing my head as it struck the seat. I was pinned down between the seats and injured my hip. There were a great many ladies in my car, most of them being killed.

“It was a bad sight. I saw many women with their heads and necks cut and breasts badly mutilated. I worked trying to save what few I could, until the railroad men came. I was very lucky, as most all in that car were killed.”

Mr. Bowthorp’s experience – His account and theory of the disaster – Was the bridge defective?

Last night was a night of mourning in Roslindale. It seemed as if every second house contained a victim of the accident, while in some cases as many as four sufferers were collected under a single roof. If there were no victims of the disaster in a house, there were so many friends of the family injured, some in the next house, across the street or just around the corner, that every one felt as if he had received a personal affliction.

This beautiful little village witnessed scenes of horror all day long. From the time of the accident till late into the day victims were being brought to the village in carriages and wagons of every description. They were taken to the station-house first, and from thence were removed to their homes.

Elias T. Bowthorp, who lives on Poplar Street, Roslindale, was in the third car that went over the bridge. He was shaken up a little, but otherwise is all right. He said last night: “We left Roslindale as usual, and were going at a pretty fair rate of speed when we reached the bridge. It is about half a mile and is a downgrade. The first thing I felt was a thumping and bumping, as if we were off the track, and running on the sleepers.

“Then the car began to sway, windows began to break, women screamed and everything was confusion. The car filled with smoke and dust, and we could see nothing.

“I first went to the stove and saw that that was all right. Then I smashed a window and got out. I heard the groans of the people below, and crawled over the banking to help all I could.

“I am usually apt to be made faint at the sight of the least bit of blood, but it wasn’t so today. But it was a sight that I shall never forget. Yet I worked steadily, assisting all I could in getting out the people.

“It seemed to me as if the fourth car fell right down into the street, and the other cars fell on top of it.

“It seemed to me as if the accident was about this way: I think that some part of the running gear on one of the cars broke, and let the cars down onto the bridge. Then, by their momentum dragging along the bridge they broke it down. This seems the natural case, because the engine went over safely.

“That bridge was called the ‘Tin Bridge,’ because there used to be a an old wooden bridge there, which was covered with tin to keep from wearing out. A number of years ago this iron bridge was built, but the name of ‘Tin Bridge’ was still retained.

“This was a worse accident than that at White River Junction, because here all the people knew each other. They all came from right along this district, and where anyone escaped, many of his friends were killed or wounded.”

Mr. Dunham’s story – Heartrending scenes – Helping victims from the ruins

Benjamin W. Dunham, 18 years old, resides with his father, Thomas H. Dunham Jr., and works for Hussey, Howe & Co., dealers in steel, 127 Oliver Street, Boston. When asked about the accident he said: “I occupied the third car from the rear, but it appears that Providence favored the occupants of our coach, for it remained upright, although the trucks were torn from it in the descent and left hanging over the abutment of the bridge. The car struck on end, but settled back and lay directly across the roadway. It looked, from its position, as though the car had dropped directly down from the track. I was thrown from my seat and struck against Miss Minnie Becker of this place. Both of my legs are considerably bruised, and my neck is slightly sprained, but I consider myself exceedingly fortunate to get out as well as I did. The first thought that came to me was of fire, and I hastily closed the stove door. I had no sooner done this and turned around than I saw an old gentleman falling backward, and reaching out my arms I prevented him from striking the floor. I discovered that the man had fainted, and with the assistance of another man succeeded in getting the prostrate man through a window. I was the last person to leave the car. The number in the car, I should say, was about fifteen, and although all were more or less injured, none, I think, were seriously. A more sorrowful scene than met my gaze when I got outside of the car I do not care to see. I assisted in getting Joseph Metcalf out of the wreck, and the condition of the man was perfectly awful. His right eye had literally been torn from the socket, the right ear was terribly mangled and his face was covered with blood from wounds in both head and face. He was also injured about the chest. In this condition he managed to crawl part way through a window, and with the assistance of another man we got him to the ground. When asked if he wished to be sent to the hospital he replied very emphatically, “No.” Mr. Metcalf is an employee of William Jessop & Son, dealers in steel, Fort Hill Square, Boston.

Rescuing the injured – Henry A. Wood narrates the scenes he witnessed

Henry A. Wood lives on South Street and started for Boston on the ill-fated train. He was found in bed. He said: “I occupied a seat in the car next to the smoker. I heard a noise as the engine and first car got onto the bridge, and looking out of a window saw what appeared to me to be the truss of the bridge swaying to the right and the cars immediately dropped with a terrible crash. I was thrown from my seat against the door, and when I regained my feet I looked around for a way to get out. Taking hold of the door I was fortunate enough to tear it from its hinges. Having found an exit for myself, I looked around to see if I could be of assistance to others. I saw Conductor Drake lying in the aisle of the car. I went to him, but he was unable to arise. With the help of a brakeman I managed to get him upon his feet and out of the car. I then turned my attention toward rescuing others. The smoker I found completely turned over. I entered this car through a window, and assisted in getting out six or seven people who were more or less injured, and I think one or two were dead. The first three that were removed were taken directly from under the stove that hung from the floor. I went to the other end of the wrecked train, and the scene there was even more appalling. I saw the mutilated remains of three women lying on broken car seats, where they had been placed after removal from the debris. Retracing my steps, I saw what appeared to be sparks of fire in the car that was at the bottom of the wreck. I called the attention of the driver of the chemical engine to the fire, and a stream of water was turned on.”

Heroic work of rescue – Sherman Bearse’s part in caring for the dead and wounded

Sherman Bearse of Chemical Engine 4 was one of the rescuing parties in the first stage of yesterday’s awful horror at the “Tin Bridge,” and he worked hard among those who worked hardest, and all the chemical men did the same.

Bearse got Mr. Clapp out of the ruins, and took him in a team and started for Forest Hills Station. He received a live man and delivered a dead one, the unhappy man expiring on the way to the station.

Bearse says that a large proportion of the injured were in the third and fourth cars from the engine, and his description of the sufferings of some of the victims is harrowing. Some of them, he says, had to bear excruciating agony. Bearse assisted in removing many of the bodies. That of Alice Burnett of Roslindale was, as far as the face went, unrecognizable, her face being smashed into a jelly. He identified her by some very peculiar buttons on her dress which he had often noticed as she passed the engine house.

Fireman Pickard’s story – How the wreck appeared to him this morning – The alarm from Box 258

Fireman P.W.A. Pickard of Engine 18 was one of the first in the department to arrive on the scene. Said he: “When the alarm from Box 258 came in we started out in quick order, never mistrusting of the fearful picture we were to gaze upon when we arrived at our destination.

“The wreck appeared very much as it does now, except that the dead and injured were still in the debris. Groans and cries greeted our ears as we arrived upon the scene; but it was comparatively quiet considering the magnitude of the accident, and large number injured. There was, by some miraculous dispensation, no sign of fire, except in one corner and this was quickly extinguished by Chemical 4, which was the only one to put on a stream.

“The whole scene looked like a gigantic kindling-wood factory that had been blown up by dynamite. That’s the best description I can give of it. When we arrived on the scene, the work of bringing out the bodies of the dead and rescuing the multitude of injured had already begun, and we at once set to work to assist. Assistant Engineer J.F. Hewins, who was on the spot, helped to get out two of the dead bodies, and I myself assisted in getting out the body of a woman whose face was fearfully mangled. It was a terrible sight all round, and I for one shall never forget it.”

Engineer Bowman’s statement

William F. Bowman, who is at the Massachusetts General Hospital, when seen last evening, said he has been an engineer on the Boston & Providence Railroad for upwards of 30 years. “I live,” he said, “in Dedham, and was coming to Boston to take the 10:30 o’clock train out. I was seated in one of the rear seats of the smoker, when I felt a jar, and the next moment I saw a man who had occupied one of the front seats, and who had stepped into the aisle, thrown to the floor. I saw at once there was some trouble and started to leave the car, and had just opened the door when I heard a crash and was thrown back into the aisle. I don’t remember how I got out, but when I came to I was on the embankment. I tried to move but my back and thigh pained me so that two men had to carry me to a safe place.”

More stories told in sorrow

George C. Barnes of Roslindale, employed at Sturtevant’s factory, was also one of the men who took part in the rescue and relief of the victims. Mr. Barnes says that as soon as the news came every man in the factory dropped his work and made haste to the scene of death and suffering, and did all they could to assist the unfortunates. “I found a woman in the fourth car” said he, whose head and arm were cut off clean as a whistle. It was about the most horrible sight I ever saw. She was a medium sized woman, and although her face was terribly mutilated, it was evident that she must have been pretty. Officer McCausland helped me get her out.”

George Davidson of Roslin Avenue, Roslindale, was on the train, but escaped uninjured. He adds his evidence as to the horrible nature of the calamity, and the struggles and agony of the victims. He was in the first car behind the engine, and was so dazed that he was the last man to leave it.

J.B. Dunn of The Globe counting room is blessing his luck that he was afflicted with a sore foot yesterday. The ill-fated train was the one which usually brings him to his daily avocation in the city. Yesterday morning he sent in word that he was detained at home by his troublesome foot. Last night he was inclined to consider that visitation as the light of Providence, for it may have saved his life.

Looked like a corpse – Mary Murphy picked up lifeless – Other remarkable cases

The case of Mary Murphy of Roslindale was a most remarkable one. When she was taken from the wreck, it was supposed that she was dead. She was taken to her home. Mrs. Dame, who attended her, said that she looked so much like a dead person that they had begun to prepare for her burial, when she came out of her state of unconsciousness. Miss Murphy was very low last night, and was not expected to live.

Another remarkable case was that of an unknown man, who assured people about him that “he was all right.” His cap had fallen off, and he raised his jacket to throw it over his head, and fell back dead.

Webster Clapp of Central Station was carried to Forest Hills Station terribly mangled, but still alive. An attempt was made to pour some brandy down his throat, but he choked and died. He was identified by his season ticket and was taken home, but his own mother could not identify him except by his clothing and season ticket.

Dismay in Dedham – Mourning for the dead and trying to help the injured

All day long the rumors came and went – rumors that threw the little town of Dedham into a state of unprecedented excitement, and that, horrible as they were, but feebly presaged the awful reality. These stories came from time to time by messengers from the scene of the frightful wreck.

Scarcely an hour elapsed before the dread news of the accident reached the town and spread like wildfire from its one extremity to the other. Yet another hour and an impenetrable crowd surrounded the central depot, thousands anxiously, with beating hearts and tear-stained faces, awaiting the coming of tidings that should feed their flickering hopes or confirm their fears in regards to the loved one, who had gathered with them but a short time before around the family breakfast table. Hundreds of others, too impatient to tolerate any delay, jumped into private or hired carriages, and hastened to the fatal spot. There they saw a sight they will never forget. As one strong man – it was Mr. Hayden of Central Station – expressed it: “I would give $5,000 this minute to have that awful sickening scene taken from my mind.”

As the day wore on the details of the disaster became more definite, and, when the gathering darkness had settled down upon the town, it enveloped in its blackness many a desolate fireside with many a sorrowing soul and many a sad, sad, heart. The gloom of that night without was not deeper than that of the stricken homes within.

Lizzie Walton and Lizzie Mandeville

Among the cases of death in Dedham Centre, none are more touching than those of the two young girls, Lizzie Walton and Lizzie Mandeville. The family of the former lives on East Street. The father, a man of middle age, is an engineer on the Providence Railroad, as also is an uncle of the unfortunate girl. She was tall and slender in figure, with long dark hair and radiant in the beauty of her 16 years. By her side in the car sat the Mandeville girl. Her family lives on Harvard Street, her father being a night watchman on the Providence Railroad. He was seen during the afternoon by some of his townsmen, wandering around the streets, frenzied with grief. He turned neither to the right nor to the left and spoke to no one, even when addressed. When last seen he was going toward home in company with Rev. Father Hurley of the Catholic Church.

“Yes,” said Mr. Walton to the writer, “God knows it’s a sad blow to my dear wife and me. We’ve six of them left yet, three boys and three girls, but it does seem that now she’s gone she was the dearest to us of all. We are looking for her poor mangled body to be brought home to us at any moment. It is in charge of Undertaker Waterman.”

Walter J. Dudley

It was reported in the afternoon papers that Walter J. Dudley was on the train and was missing. A call at his house, however, revealed the fact that he was safe and sound.

Winfield W. Smith

Winfield W. Smith, a brakeman, 27 years old, living with his sister, had his hip broken and his back hurt. He was taken to City Hospital, where he was seen by his sister during the afternoon. She stated last evening to a Globe reporter: “My brother, so the doctors tell me, will get well. We belong in Maine. He has been on the railroad about three years. I feel thankful that his injuries are no worse.”

Webster Drake

Webster Drake, who is a Conductor on the railroad, boards with Mrs. E.G. Spaulding on Spruce Street. He was considerably injured and taken to the hospital. He is about 30 years of age, had been on the railroad about ten years, and, as one of the officials at the depot said: “He was a mighty nice fellow.”

Hattie Hill

Of all the heartrending scenes witnessed by the reporters on their dismal tour of the stricken town perhaps the most pathetic was at the home of Mrs. Sarah W. Hill on Anawan Avenue, Central Station. In a modest, two-story cottage lived the old lady with her two daughters. One is Hattie, from whose mind the light of reason long ago departed: the other, Emma, a sweet-faced girl of 23, whose daily work at R.H. White’s was the sole support of the little family. As the reporter’s carriage drew up to the gate a number of neighbors, who had heard of the woman’s affliction, were about entering the house, while, at the very next door, through the gloom of the night could be seen the dim outline of an undertaker’s wagon. The undertaker had brought to the Swaben family its beloved and mangled dead. Across the kitchen floor feebly tottered the old lady, her snowy hair disheveled. Her voice was broken by sobs: “I’m glad to see you – all of you – but I don’t see the dear face of my angel daughter.”

A sob choked her utterance, and a hush fell upon all in the room. Then continuing, she cried wildly: “Oh, God! Can it be true! To think that there in that room lays all that remains of her! You can look upon her, if you will – but not her head, not her head! It is too cruelly mangled.

She was such a good girl! She never gave me an hour’s trouble, and never told me a single falsehood. God help me! Oh! God help me to bear this! Am now I am left alone – alone! How can I bear it? Hattie, dear, would talk with me, but alas she cannot. But God will loose her tongue someday, and we shall all talk together in heaven. It won’t be long. It won’t be long.”

The old lady leaned her head feebly back upon the chair, while one of those who stood by in silence bathed her feverish forehead.

“That’s a sad case,” said Mr. Hayden, afterward. The dead girl’s father was the late Jonathan Hill, and since his death the family has been in very straitened circumstances. I know there isn’t a particle of coal in the house today, and that Mrs. Hill owes a large bill at the store.”

Edward E. Norris