A Holocaust Survivor Returns to Jamaica Plain

How a chance meeting on JP’s Boylston Street reveals a Holocaust survivor’s brief connection with Jamaica Plain 80 years ago.

By Peter O’Brien, December, 2009

Ed looks out the window of 257 Lamartine St. in 1931A member of the Jamaica Plain Historical Society happened to be on Boylston Street in early November 2009 and, by chance, met a couple from Hastings on Hudson, New York, who were looking for a certain house on Lamartine Street. The couple, Edward Lessing and his wife Carla, were looking for the house at 257 Lamartine where Ed had lived in the early 1930s. After a short residence there, Ed Lessing’s story took many turns with several unplanned surprises including life-threatening experiences with the Nazis and his mother’s internment in a notorious concentration camp during World War II. This amazing story about a Dutch family displaced by the Holocaust and happily reunited after the war, might never have happened if the patriarch, a cellist, could have found work and remained in Jamaica Plain during those pre-war depression years.

Ed looks out the window of 257 Lamartine St. in 1931A member of the Jamaica Plain Historical Society happened to be on Boylston Street in early November 2009 and, by chance, met a couple from Hastings on Hudson, New York, who were looking for a certain house on Lamartine Street. The couple, Edward Lessing and his wife Carla, were looking for the house at 257 Lamartine where Ed had lived in the early 1930s. After a short residence there, Ed Lessing’s story took many turns with several unplanned surprises including life-threatening experiences with the Nazis and his mother’s internment in a notorious concentration camp during World War II. This amazing story about a Dutch family displaced by the Holocaust and happily reunited after the war, might never have happened if the patriarch, a cellist, could have found work and remained in Jamaica Plain during those pre-war depression years.

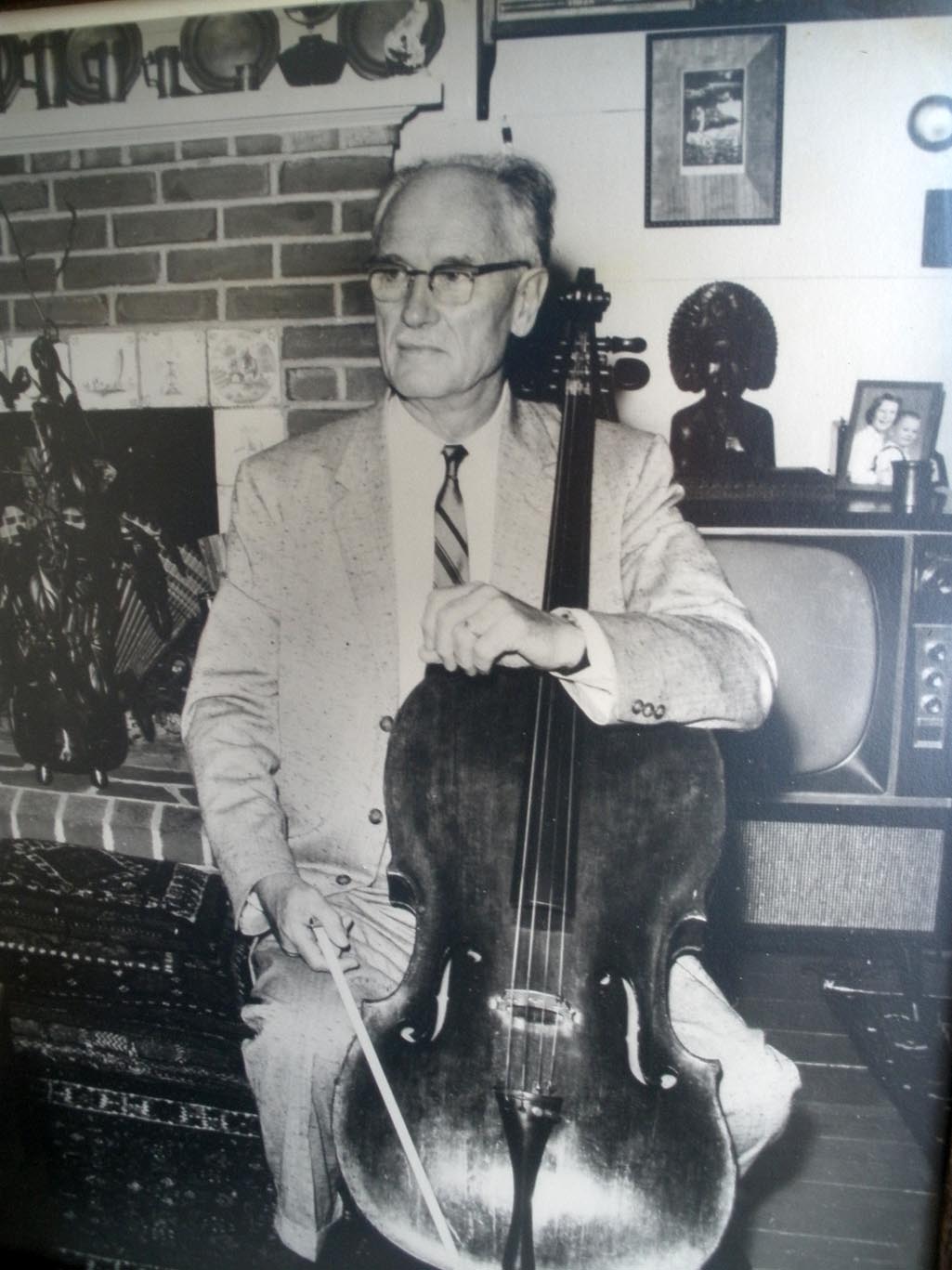

The Lessings Leave Holland Ed with his father in BostonThe story starts in 1929 when a Dutch Jewish couple, Nathan ‘Nardus’ Lessing, his wife Engeline ‘Lien’ Elizabeth, (nee van Leer,) and their three-year old son Eddie arrived in America. They were greeted by Lien’s sister, Suze and her husband David (Cohen) van Leer who had emigrated to the United States earlier and had settled in what was then the most Catholic (97%) city in the USA; Holyoke, Massachusetts. They tried fruitlessly to rent an apartment there until a friend told them that with a name like Cohen, they would never succeed. David and Suze then changed their name, legally, to van Leer and never thereafter told anyone that they were Jewish. David van Leer worked in a typography company while Suze worked as a bookkeeper. The van Leers never left Holyoke.

Ed with his father in BostonThe story starts in 1929 when a Dutch Jewish couple, Nathan ‘Nardus’ Lessing, his wife Engeline ‘Lien’ Elizabeth, (nee van Leer,) and their three-year old son Eddie arrived in America. They were greeted by Lien’s sister, Suze and her husband David (Cohen) van Leer who had emigrated to the United States earlier and had settled in what was then the most Catholic (97%) city in the USA; Holyoke, Massachusetts. They tried fruitlessly to rent an apartment there until a friend told them that with a name like Cohen, they would never succeed. David and Suze then changed their name, legally, to van Leer and never thereafter told anyone that they were Jewish. David van Leer worked in a typography company while Suze worked as a bookkeeper. The van Leers never left Holyoke.

A New Friend Tries To Help

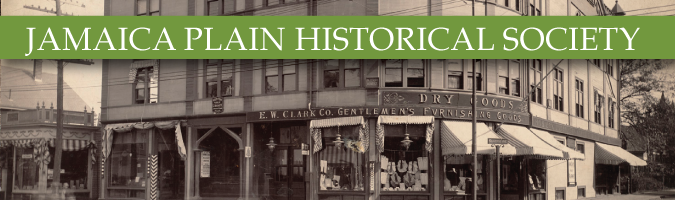

Nardus Lessing, an accomplished cellist, had studied at the Music Conservatory in The Hague, Netherlands, until his father told him that he had had enough education and he should now find a job in music somewhere. He was soon hired as a member of a musical trio on a ship that sailed for Cuba. He also made several working trips to New York on ships of the Holland-America Line. A few times he visited his sister-in-law Suze and husband David van Leer in Holyoke during his New York layovers. Jacobus Langendoen with celloWhen the family emigrated, Nardus had hoped to find steady work in America through Jacobus ‘Jaap’ Langendoen, a Dutch cellist with the Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO), which was then under the direction of Serge Koussevitzky (1924-1949). The family tradition is that Nardus may have met Jaap through his sister-in-law, Suze van Leer, of Holyoke. Langendoen at that time lived at 17 Pearl Street in Dorchester. Jaap’s granddaughter, Heidi Langendoen, of Wakefield, Massachusetts, fondly recalls her grandfather as someone who would try very hard to help another musician and that he mentored many young musicians over his long career. She remembers hearing about his summer work playing at the Wentworth Hotel in the town of New Castle, New Hampshire. Later, the Langendoen’s bought a house and resided there for many years.

Jacobus Langendoen with celloWhen the family emigrated, Nardus had hoped to find steady work in America through Jacobus ‘Jaap’ Langendoen, a Dutch cellist with the Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO), which was then under the direction of Serge Koussevitzky (1924-1949). The family tradition is that Nardus may have met Jaap through his sister-in-law, Suze van Leer, of Holyoke. Langendoen at that time lived at 17 Pearl Street in Dorchester. Jaap’s granddaughter, Heidi Langendoen, of Wakefield, Massachusetts, fondly recalls her grandfather as someone who would try very hard to help another musician and that he mentored many young musicians over his long career. She remembers hearing about his summer work playing at the Wentworth Hotel in the town of New Castle, New Hampshire. Later, the Langendoen’s bought a house and resided there for many years.

The kindly Jaap Langendoen will appear again after the war to help another member of the Lessing family.

Untimely Illness

Unfortunately, Jaap Langendoen’s helping hand could not be accepted because Nardus contracted tuberculosis and was hospitalized in Holyoke. There was a small 50-bed Holyoke City Sanatorium on Cherry Street, Holyoke, which had been under the direction of Dr. Carl Rosenbloom. The 1930 census lists Nathan Lessing and several other patients and staff as residents at the Holyoke City Sanatorium. In those days before effective TB drug therapy was developed in the early 50’s, patients’ recovery rates were not good.

Following this health disaster, Nardus’ wife, Lien, and their son Eddie, found themselves living in a two-family house at 257 Lamartine Street, Jamaica Plain.

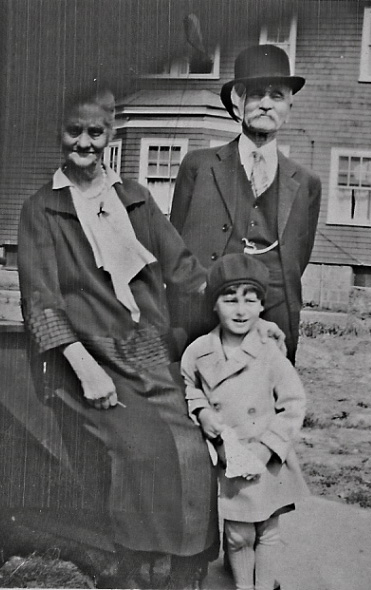

Only in America Ed’s ‘adopted’ grandparentsLien, a very enterprising former telegraph operator, first of all searched for and found an elderly couple to take care of Eddie during the daytime. Eddie fondly remembers them only as Grandma and Grandpa, a kindly couple whose surname cannot be recalled.

Ed’s ‘adopted’ grandparentsLien, a very enterprising former telegraph operator, first of all searched for and found an elderly couple to take care of Eddie during the daytime. Eddie fondly remembers them only as Grandma and Grandpa, a kindly couple whose surname cannot be recalled.

Lien then found employment with Mr. Ben Franklin Allen who owned a small travel bureau called “Allen Tours” on the second floor at 154-156 Boylston Street, Boston, a six-story building located across from Boston Common between Tremont and Charles Streets, in what is now the Piano Row Historic District. The first floor at 156 Boylston Street was occupied by the New England Piano Company. Ben Franklin Allen lived at 12 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston.

Ed Lessing clearly remembers Allen’s name because of an incident his mother related much later. It seems a former travel client sent a letter addressed to Mr. Allen at “Allen Tours.” Lien opened it and it read: “Dear Mr. Allen, - I do not know anyone whom I hate enough to let him suffer one of your tours! Sincerely etc.” Lien, torn between duty and fear of an executive outburst finally got up the courage to hand the offending letter to Mr. Allen. As she said years later, “I could not believe what happened. Mr. Allen read the letter twice, then burst out in uncontrollable laughter and shouted, ‘The best letter I ever received. Let’s frame it!’ And so it was done, and Mr. Allen proudly hung it over his own desk.” Eddie always remembered this story as proof that there was no country in the world like America where such a thing could happen!

Health Restored

In 1931, in what was a very lucky outcome for the period, Nardus recovered. He then found summer work through Jaap Langendoen, as a cellist with 11 other members of the BSO, at the grand Wentworth Hotel in New Castle, New Hampshire.  BSO group at Wentworth in 1931The family moved to New Hampshire and enjoyed a happy summer there while that music engagement lasted, remaining hopeful that a more permanent job in music could be found. Ed Lessing’s photographs from that memorable summer show him playing in the water with his mom. Nearly 80 years later, on their way to a conference in Boston, Ed and Carla Lessing stayed at the same Wentworth Hotel and presented them with a picture of those summer of ‘31 musicians, which included Ed’s dad, Nardus Lessing.

BSO group at Wentworth in 1931The family moved to New Hampshire and enjoyed a happy summer there while that music engagement lasted, remaining hopeful that a more permanent job in music could be found. Ed Lessing’s photographs from that memorable summer show him playing in the water with his mom. Nearly 80 years later, on their way to a conference in Boston, Ed and Carla Lessing stayed at the same Wentworth Hotel and presented them with a picture of those summer of ‘31 musicians, which included Ed’s dad, Nardus Lessing.

As the depression deepened permanent work could not be found, and in 1932, three years after their arrival, and with only the summer work at Wentworth Hotel and Lien’s job at Allen Tours having sustained them, the Lessings had to return to the Netherlands.

Back Home in Holland

After their return, the Lessings finally settled in the small historical town of Delft, located near Rotterdam. Delft is noted as a most typical Dutch town with a canal passing right through the town center. It was the home of the noted painter, Johannes Vermeer and the world-famous Delft pottery.

The Lessings, struggling through the depression at whatever work that could be found, had three more sons, one of whom died at nine months.

World War II Arrives in Holland

By May 1940, the Lessing family of Nardus, Lien, Eddie (14), Arthur ‘At’ (6) and Alfred ‘Fred’ (4) had become part of the community living on the canal in Delft. At that time Hitler’s troops overran Holland’s little democracy and installed a Nazi government there led by a friend of the Führer, The Reichskommissar for the Occupied Dutch Territories, Dr. Seyss Inquart, who was hanged after the war as a war criminal.

As a non-religious, though, nevertheless, a Jewish family, the Lessings found themselves in immediate danger. It took the Nazis just three years in Holland to accomplish what they did in their own country in six years, i.e. to destroy the age-old Jewish communities by murdering its members, irrespective of age or gender, in death camps located in Nazi-occupied Poland.

Nardus and Lien saw that the only way to survive with their three boys was to go into hiding from the Gestapo, the Secret German Police. Thus, on October 22, 1942, the Lessings dispersed and disappeared.  Ed with his mother in New Hampshire in 1931At that point, Eddie’s mother, Engeline Elizabeth Lessing/van Leer changed from housewife to heroine, fighting to save the lives of her entire family. First, she secured a false ID card with a new name from the Dutch Resistance. She then began to travel through Holland with the false ID on the extremely dangerous, constantly Gestapo-patrolled trains to find hiding places for her sons, her husband and herself.

Ed with his mother in New Hampshire in 1931At that point, Eddie’s mother, Engeline Elizabeth Lessing/van Leer changed from housewife to heroine, fighting to save the lives of her entire family. First, she secured a false ID card with a new name from the Dutch Resistance. She then began to travel through Holland with the false ID on the extremely dangerous, constantly Gestapo-patrolled trains to find hiding places for her sons, her husband and herself.

At great personal risk, she succeeded in placing all in fairly secure locations with trusted Dutch families. Lien and Nardus were taken in by a brave gentile family who hid them for two years. As the war wore on, however, Lien had to find new safe houses for her younger sons Fred, aged six, and At, aged eight.

Rescued From the Nazis

Her eldest son, Eddie, 17, wound up with a group of Dutch Resistance men in their headquarters hut in the woods in the center of Holland, near the tiny village of De Lage Vuursche, in the Dutch province of Utrecht. At dawn on December 29, 1943, German forces arrived to arrest and/or kill the Resistance group. Eddie was standing watch at the time and he and his partner barely had time to warn the six men sleeping in the hut and save themselves. The men quickly dressed and scattered into the forest.

As part of a contingency plan in the event of such a raid, at eight o’clock that evening, Eddie and his partner went to a designated meeting place in the woods, about seven miles from the hut, where they hoped to meet any survivors of that morning’s raid. At the meeting place they were armed with 9mm Mauser pistols in case of a surprise German attack. Soon, in the pitch-black darkness, someone arrived on a bicycle. Fearing that it was a German trap, Eddie and his friend held their fire. And they were thankful they didn’t shoot when they discovered that it was neither the survivors of the raid on the hut nor German troops that had arrived, but to their astonishment, the bicyclist was found to be Eddie’s mother, Lien!

Lien explained to Eddie that as soon as she heard about the raid on the hut, she “immediately decided to try and rescue you.” She then explained that they were completely surrounded by a large circle of Wehrmacht and SS troops looking for them and that they should immediately bury their weapons to avoid being killed when arrested.

When the weapons were buried, Eddie’s partner accepted Lien’s bicycle and flashlight and left to find a hiding place leaving Eddie and Lien standing in the dark, surrounded by Germans. At this moment, Lien conceived a desperate plan to survive as they walked towards the encircling German troops waiting to capture them. They soon came to a German soldier pacing with a shouldered rifle and immediately executed Lien’s plan. Tightly hugging each other in an embrace with heads close together they began talking and laughing loudly, while making kissing sounds. As they approached the German soldier, they waved to him with a wide smile on their faces and ice-cold fear in their hearts. He stopped them with a loud HALT! - - - and they kept the grins on their faces as he made up his mind. It was at that moment a life or death decision for the two of them. Suddenly he shouted, “Nah also, gehen sie!” (Now then, get going) as he waved them on. They thanked him profusely with many loud “Danke schons” (thank you’s) and thus they walked out of that circle of death to live another day.

Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp Ed (standing right) with Leni Langendoen (in the background)In May 1944, Lien was on her way to find a new hiding place for her youngest child, Fred, when she ran into a Gestapo specialist on a Dutch train. He immediately recognized her false ID card and she was arrested. She was put in a separate train compartment with a civilian Dutch police officer to guard her on her way to Gestapo Headquarters in Amsterdam. Realizing that she had all the family members’ hiding-place addresses in her handbag, she surreptitiously tore each piece of paper in shreds, chewed it up and swallowed it, to arrive in front of the Gestapo interrogators with only her false ID card.

Ed (standing right) with Leni Langendoen (in the background)In May 1944, Lien was on her way to find a new hiding place for her youngest child, Fred, when she ran into a Gestapo specialist on a Dutch train. He immediately recognized her false ID card and she was arrested. She was put in a separate train compartment with a civilian Dutch police officer to guard her on her way to Gestapo Headquarters in Amsterdam. Realizing that she had all the family members’ hiding-place addresses in her handbag, she surreptitiously tore each piece of paper in shreds, chewed it up and swallowed it, to arrive in front of the Gestapo interrogators with only her false ID card.

“Who are you?” she was asked. “I am Engeline Elizabeth van Leer”

“Do you have a husband?” “Yes, he is in the U.S. Merchant Marine.”

“Do you have children?” “No, I have no children.” And then, out of the blue, she shouted, “You have no right to keep me here. I am an American citizen!”

The Gestapo agent, having heard every Jewish excuse to prevent their imprisonment or death, asked her the next question: “Well, Mrs. van Leer, if you are, as you claim, an American citizen, you have, no doubt, no problem giving us an address where you have lived or where your husband lives in the United States?” And she, with unfailing memory of 1931, answers the Gestapo interrogators: “No, I have no problem - - 257 Lamartine Street, Jamaica Plain, Boston, Massachusetts.”

As the interrogator wrote down her response, Lien heard a German officer behind her saying, “Well, that’s no fake, she knows where she lives.” Nevertheless, she was eventually sent to the infamous Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in northern Germany where she managed to barely stay alive by getting a night job in a kitchen where she could sometimes steal half a potato.

Then, one morning in January 1945, returning at dawn to her barracks, she is told by her bunk-friend to present herself to an SS officer who is checking on people with foreign nationalities. “Why?” she asks. “You told them you are an American,” her friend answered. Lien responded, “You know, I just made it up,” but her friend nevertheless urged her on and Lien presented herself to the SS guard. He checked a list and told her that in two days she’d be on a transport out of the camp, to be exchanged for a German citizen.

Two days later, with 300 other sick and dying prisoners of Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, she was put on a train that traveled to St. Gallen, a border town in northeastern Switzerland, where they were exchanged; ironically, for Germans coming from Palestine where they had been interned as enemies by the British.

Lien chose not to go to her sister Suze in America, but rather to stay in a United Nations Rehabilitation camp, winding up in Camp Jeanne d’Arc, in Algiers on the North African coast.

When the war finally ended, Lien hitchhiked a ride on an American bomber and was reunited with Nardus, Ed, At and Fred once again in Delft.

Starting Again in America

Soon after the war, the Lessings again immigrated to America. All except 21 year old Ed, settled in Springfield, Massachusetts, where Nardus taught cello, Lien became a buyer in a hardware store, and Ed’s brothers At and Fred attended college; both becoming professors of philosophy.

Ed’s brother, At, however, had earlier considered a career in music and actually took cello lessons for a year from none other than Jaap Langendoen! At recalls that every Sunday he would take the bus to Newton Upper Falls and have his lesson from Jaap who was expert in the bowing of the cello and the instrument’s technical demands. Jaap’s wife, Leni, would then serve a hearty lunch for the three of them. Jaap would then head for his BSO matinee and drop At off at the bus station. On the way, At would ask Jaap what music was to be played that afternoon and Jaap would reply, “I’ll find out when I get there!”

Continuing his help to the Lessings, Jaap Langendoen got At a full summer scholarship in 1954 to study with the BSO at Tanglewood where Leonard Bernstein was conductor of the student orchestra. However, realizing that music was not to be his life’s work, At began a new life that fall and went on to study at Wesleyan. He never stopped playing the cello, however, and to this day uses finger warm-up techniques taught him by his respected mentor, Jaap Langendoen.

Ed Lessing pursued a career as an independent graphics designer and is now retired. He devotes much of his time to lecturing and writing about the Holocaust. He occasionally finds time to build a WWII model airplane.

Ed’s Dutch wife, Carla, also survived the Holocaust. In 1942, at age 12, she began to live as a “hidden child” in Nazi occupied Holland. The hidden children were the Jewish kids whose parents chose to place them anywhere survival was even remotely possible. These children lived for extended periods with kind (and sometimes not-so-kind) host families, in convents and churches, in barns, attics, caves, cellars and even in sewers to escape the Nazis searching for people to send to the labor and death camps. All who would rescue these terrified children and their families were themselves at risk of death or deportation for harboring them. Carla spent years moving to and from hiding places in Holland and despite several stressful close-calls she survived to meet and marry Ed Lessing and come to America with him after the war. Her memories, as with many of the hidden children, are very painful, confusing and rife with carried-over anxieties and fears. With the background of these life experiences she became a caring and effective psychotherapist and an active officer of the Hidden Children Foundation/ADL, a New York-based survivor’s group. Ed Lessing, 2009Over the intervening years Eddie has often wondered what became of the men in the hut and especially his partner who rode off into the night on his mother’s bicycle. Fifty years later he was to learn that all the hut’s occupants, including two downed Royal Air Force airmen, had escaped. One of the airmen, Fred Sutherland, a full Cree Indian, was a crew member of the famous RAF Squadron 617 bomber group known as the “Dam Busters.” And, contrary to Eddie’s long-standing memory of the partner being a certain resistance fighter who was later killed by the Nazis, the actual partner was in fact alive and serving as a Catholic Bishop in New Guinea! Ed was reunited with Bishop Herman Munninghoff in Holland in 1992 where the Bishop recounted the exact same version of the terrifying night of the raid on the little hut in the woods, his own dangerous escape on Lien’s bicycle and his later calling to the priesthood … all thanks to Eddie’s mom.

Ed Lessing, 2009Over the intervening years Eddie has often wondered what became of the men in the hut and especially his partner who rode off into the night on his mother’s bicycle. Fifty years later he was to learn that all the hut’s occupants, including two downed Royal Air Force airmen, had escaped. One of the airmen, Fred Sutherland, a full Cree Indian, was a crew member of the famous RAF Squadron 617 bomber group known as the “Dam Busters.” And, contrary to Eddie’s long-standing memory of the partner being a certain resistance fighter who was later killed by the Nazis, the actual partner was in fact alive and serving as a Catholic Bishop in New Guinea! Ed was reunited with Bishop Herman Munninghoff in Holland in 1992 where the Bishop recounted the exact same version of the terrifying night of the raid on the little hut in the woods, his own dangerous escape on Lien’s bicycle and his later calling to the priesthood … all thanks to Eddie’s mom.

The Lessing’s dramatic stories of evading the Nazis and surviving the Holocaust as children, hiding alone or with host families in occupied Holland, are told in the book “The Hidden Children – The Secret Survivors of the Holocaust” by Jane Marks.

Ed and Carla live in Hastings on Hudson, New York. They have two children; Noa, born in Israel and Dan born in the United States and four grandchildren.

Epilogue 257 Lamartine, 2009While many of us were collecting paper and scrap metal, and buying war bonds and stamps to win the war, a nimble-minded Dutch mom was outwitting her Nazi captors and surviving one of the most notorious concentration camps to become an exchanged prisoner and thus live to see her family reunited after the horror called the Holocaust.

257 Lamartine, 2009While many of us were collecting paper and scrap metal, and buying war bonds and stamps to win the war, a nimble-minded Dutch mom was outwitting her Nazi captors and surviving one of the most notorious concentration camps to become an exchanged prisoner and thus live to see her family reunited after the horror called the Holocaust.

And, had a kind-hearted attempt to find music work for her husband (who never served as a Merchant Mariner except as a cruise ship musician) by Jacobus “Jaap” Langendoen succeeded back in 1930, 257 Lamartine Street might only be remembered today as just another Jamaica Plain two-decker instead of an important landmark in the world of a courageous Dutch family.

Sources and References:

Sheldon Rotenberg, retired Boston Symphony Orchestra violinist, Brookline MA

Heidi Langendoen, Jacobus Langendoen’s granddaughter,Wakefield MA

Bridget Carr, Boston Symphony Orchestra Archivist

Books:

“The Boston Symphony Orchestra, 1881-1931” by Mark Anthony DeWolfe Howe, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1931

“Gentlemen, More Dolce Please” by Harry Ellis Dickson, Boston: Beacon Press, 1969

“I had put all that behind me years ago” copyright monograph by Edward Lessing, 1994

“The Hidden Children – The Secret Survivors of the Holocaust” by Jane Marks, New York: Ballantine Books, 1993