257 Lamartine Street

It was mere chance that found Jamaica Plain Historical Society member Fran Perkins on Boylston Street that November day in 2009 when she met a group of people from New York, looking a bit lost, who were trying to find a house at 257 Lamartine Street where one of them had lived in 1930. Fran’s conversation with the group led to our story “A Holocaust Survivor Returns to Jamaica Plain” in which the house at 257 Lamartine plays a prominent role.

Soon after the writing of the Holocaust story began, another coincidence emerged. We received an inquiry from a family in Connecticut seeking information about one of their ancestors, a German immigrant, who lived and died in Jamaica Plain in the 1920s. The ancestor, Jacob C. Becker (aka Carl Becker), a veteran of the Spanish American War, lived at 267 Lamartine Street in 1920. His daughter, Emily, married a Lawrence R. Grove and they lived, of all places, across the street at 257 Lamartine Street, which became the home of our Holocaust survivor some ten years later! We tried, but failed to find a connection between the Groves and the Lessings, the family in the Holocaust story, other than they lived in the same house, 10 years apart. The Groves, of 257 Lamartine, had a daughter Lorna, who was the mother of our Connecticut respondent.

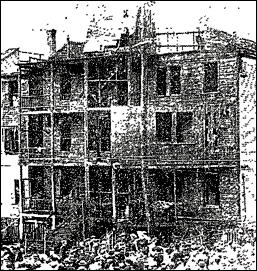

Moving from Lamartine Street, the family tradition says that Carl Becker lived in the Chelsea Soldiers’ Home. Sadly, after he moved to the Soldiers’ Home, the tradition says that during a visit back to 267 Lamartine in the late summer of 1924, a tenant there provided Carl with more homemade beer than he could handle and he wandered to Jamaica Pond, fell in, and drowned.  Chelsea Soldiers Home. Photograph courtesy of actonmemoriallibrary.orgThere is a Becker family plot at Forest Hills Cemetery with a headstone listing Carl along with his wife Paulina but the Cemetery has very little information about Carl. As the Becker descendants continued their search for information about Carl’s death they learned that their original belief that Carl lived in a Sailor’s Home near Egleston Square was incorrect. We had found no record of any such institution in Jamaica Plain, nor did the Naval History Library in Washington whom we queried about it. We suggested to the descendants that it might have been the Home for Aged Couples, near Egleston Square, that the Becker’s oldest living descendant (92) remembered as Carl’s residence after leaving Lamartine Street. We eventually learned that Carl did indeed live at the Chelsea Soldiers’ Home which was probably reached by public transportation from Egleston Square, which established the Egleston connection in the elderly descendant’s memory.

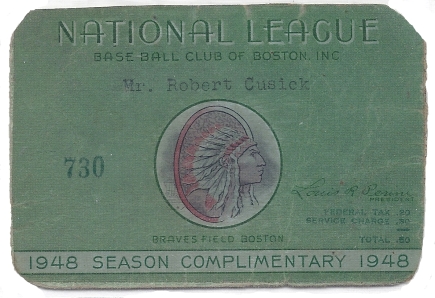

Chelsea Soldiers Home. Photograph courtesy of actonmemoriallibrary.orgThere is a Becker family plot at Forest Hills Cemetery with a headstone listing Carl along with his wife Paulina but the Cemetery has very little information about Carl. As the Becker descendants continued their search for information about Carl’s death they learned that their original belief that Carl lived in a Sailor’s Home near Egleston Square was incorrect. We had found no record of any such institution in Jamaica Plain, nor did the Naval History Library in Washington whom we queried about it. We suggested to the descendants that it might have been the Home for Aged Couples, near Egleston Square, that the Becker’s oldest living descendant (92) remembered as Carl’s residence after leaving Lamartine Street. We eventually learned that Carl did indeed live at the Chelsea Soldiers’ Home which was probably reached by public transportation from Egleston Square, which established the Egleston connection in the elderly descendant’s memory.

The coincidence of the house at 257 Lamartine playing a part in two family’s lives 80 years ago and then their stories coming to light almost simultaneously is, we think, very interesting, to say the least.

Peter O’Brien

April 15, 2010

90-year-old Cobbler Still Going Strong

By Peter O’Brien, April, 2010

What does a 1940’s type shoe repair shop, a fleet of World War Two B-17 Bombers, the Building 19 discount store in Norwood, Arthur Fiedler of Boston Pops fame and Jazz Maffie, the late Brinks bandit, have in common? And the answer is: 90 year-old cobbler Guy Perito, formerly of Sedgwick Street, Jamaica Plain!

Guy Perito stands in front of a sign in his shop at Building #19

Guy Perito stands in front of a sign in his shop at Building #19

Guy Perito was born August 23, 1920 at Ritchie Street in Jackson Square, Roxbury. Jackson Square’s intersection of Centre Street and Columbus Avenue, under the watchtower on Fort Avenue, was then a busy gateway to Roxbury Crossing on Columbus Avenue and a shortcut to Dudley Street via Centre Street. Guy knew the Square and its diverse 1930s small businesses well.

His parents were Valentino of Naples and Grace of Sicily, Italy.

His younger siblings were Johnny, Mary, Rita and Leo. Leo fought at Anzio in World War II and has passed away.

Leaving Ritchie Street the Perito family moved to a three-decker with gaslights and an oil-fired black kitchen stove that heated the flat and cooked their meals at 9 Albert Street, Roxbury. Albert Street ran from Heath to Tremont Street alongside the old raised NYNH&H railroad track bed which was later depressed below grade as part of the aborted Southwest Corridor Project.

Guy went to the Blessed Sacrament grammar school and then on to Boston Trade School where he took the popular Auto Mechanic’s course, graduating in 1939. He then took Machine Shop courses at Wentworth Institute, learning the various machine shop tools and processes. His favorite subjects in school were math, history and of course, shop. Due to his mother’s vigilant oversight of his schoolwork he was a pretty good student and was determined to never bring home an unsatisfactory report card for her signature… and he never did. Guy goes to his Trade School reunions, but notices the attendance is dwindling now. (Not many make their 70th year class reunion!)

His school years’ activities included singing in the Blessed Sacrament choir and many hours in the gym. He was an avid member of the Roxbury Boy’s Club and remembers swimming there and playing table-pool at the younger kids’ tables which featured thick wooden discs instead of ivory balls, played on a bare wood table without felt covering. He also played sandlot football for the “Pirates” and frequently enjoyed the matinees at the famous “spit box” (the Madison Theatre on Centre Street was known by many different names, depending on your neighborhood.)

Guy discovered a love of the drums and played in the Trade School drum and bugle corps as it marched in the annual Boston Schoolboy Parade. He was good enough to earn an audition for the All American Youth Orchestra. The Massachusetts’ auditions were handled at the time by Arthur Fiedler of Boston Pops fame. Guy didn’t make the cut but he certainly enjoyed meeting the famous conductor.

Guy’s father, Valentino, was a skilled shoemaker making hand crafted shoes in a shop in Needham for the affluent professionals in that town. He had learned the trade in Italy and was never out of work, even during the Great Depression. Notwithstanding his relatively secure circumstances, Guy remembers writing to the Boston Post (newspaper) Santa with a list of wanted toys, which he thinks Santa fulfilled. Thanks to Valentino’s skill however, the family weathered the Depression’s worst years in modest comfort.

Valentino commuted to Needham by public transportation until Guy bought his first car, a ‘32 Chevvie for $15 at a Jackson Square gas station. Repairing its broken axle himself, he was able to drive his dad to work much of the time. Guy has been driving since he was 16, and continues driving as he nears his 90th birthday.

Valentino eventually bought the shoe shop in Needham from its owner, Rocco Perrara, with money Guy had saved. Guy then learned the shoe-making and repair business from his father, never dreaming that one day he’d enter the declining field of shoe repair.

Guy’s working life started very young, as was the case for most youngsters in the 30s and 40s. He remembers selling the Daily Record for three cents, or a 100% markup on the penny and half he paid the distributor. In those days the paperboys could ride the El, streetcars and busses free with a Newsboy’s pass to sell papers to the commuters. The second of the two daily editions of the Record, called the “Payoff Edition,” was the more popular because it contained the daily “number” that yielded a 600 to 1 payoff on a bet with the local bookie.

Despite possessing a solid auto mechanic’s training from Boston Trade School, Guy thought he wanted to be a fireman. So, with an uncle’s encouragement, he enrolled in the Firefighter’s course at MIT and he did well in it. However, when the Boston Fireman’s test day came, Guy, upon reaching the front door at Fire Headquarters, decided he didn’t want it after all.

During his growing up years, Guy had developed a love of airplanes and built many models, starting with the simple penny balsa gliders and moving on to the more complex paper covered kit models of the famous World War One Spads, Sopworth Camels, Fokkers and other “double wingers” of that era. The fascination with airplanes grew and was fully realized when he entered the Army Air Force and became a World War Two B-17 bomber mechanic. The B-17 was one of the toughest war planes ever built and Guy loved every moment working on them from 1942-46 in Selma, Alabama. Selma then was just a small southern city, pop. 20,000, and the site of a famous Civil War battle. Twenty years later it was a major battlefield in the Civil Rights Movement of the 60s.

After the war Guy went to work for a series of auto repair shops in the Roxbury, Jamaica Plain and West Roxbury areas. Between automotive jobs he tried machine shop work and he even tried plastering for a while. His uncle Angelo owned the barbershop next to the Jamaica Theatre, above the bowling alleys, where Mayor Curley regularly had his hair cut and Guy considered that line of work also (i.e. barbering, not mayoring.) As the post war boom continued and he was getting steady work, he met Shirley (Tibbetts) of Lowell at the Clarke and White auto dealership on Commonwealth Avenue in Boston where she was working as an assistant to the Service Manager. They were married and in 1953 they moved to a three-decker on Sedgwick Street, directly across from the Jamaica Plain Branch Library. Guy knew Sammy Klass’ shoe repair shop around the corner on South Street. Sammy had a very busy shop because in those days shoes saw several reincarnations before a trip to Ed Hanlon’s for a new pair.

The Peritos had three children and three grandchildren. All of the children have advanced degrees and are working in responsible careers, making their dad very proud. In the mid-fifties Guy and Shirley moved to Needham where they live now.

After nearly 45 years in the automotive world, Guy grew tired of it and decided to try a new career. With his Dad’s training many decades earlier, Guy found a job in a shoe repair shop in Stoughton. He discovered that he liked it very much, especially the customer interaction, as he loves to talk and make new friends. The owner of that shop retired and Guy bought the tools and equipment. In the late eighties, Paul London, the shoe buyer for the Building 19 discount store chain, asked Guy if he’d be interested in opening a shoe repair shop in Building 19¾ on Route 1 in Norwood. Guy agreed and moved his newly acquired equipment in and he has been fixing shoes and meeting new friends there ever since as “Shoe Repair by Gaetano.” (Guy in Italian = Gaetano.) Over the intervening years he’s met the inimitable Jerry Ellis, one of the founders of the Building 19 organization and many other locally prominent people.

Nearing 90 now, Guy has no intention of stopping what he loves to do. His weekly “club” meeting, which he presides over, meets each Saturday in Shoe Repair by Gaetano’s at Building 19¾. The group includes friends from as far back as his Jackson Square days and newer friends he’s met in his Building 19 shop. The diverse group makes for lively and fun talk with much reminiscing and a challenge or two about a date or a place or a long-past event or person of note. The discussions, with frequent interruptions by customers picking up and dropping off shoes, range from the finer points of the 1940s pizza at Napoli Café on Columbus Avenue to where one could get a pint on a Sunday morning to the appropriateness of Jazz Maffie’s (several knew him) 18 year prison sentence at Walpole and just where did that Brinks money really go and what was the name of that restaurant on Broadway in Southie (Amrhreins?)

Guy knew Jazz Maffie and his family very well when the Maffie’s were living at the foot of Parker Hill near Heath Street. He and the others all said Jazz was a very well-liked and friendly fellow.

Some of the weekly “club” attendees are Catherine “Kay” Desimone, Emmet Tynan, John Tighe, Chester Wallace, and Rick Sidorowicz aka Mr. Sid, the former Dedham clothier. The whole scene is like a modern version of the old-time paintings of weathered, pipe smoking oldtimers sitting around the pot-belly stove in a country store, whittling and chewing the fat.

As he looks back, Guy’s fondest memory of Jamaica Plain is the 4th of July festivities at Jamaica Pond. He thinks the computer, television and the cell phone are the major innovations he’s seen in his lifetime and he’s conversant with all three. He attributes his long life and excellent health to a good wife, a healthy diet (with very little meat,) swimming and plenty of walking before he had both hips and a knee replaced. He is encouraged by the fact that some people still want to learn the shoe repair trade and he will be training a new hire very soon.

Guy and Shirley were big fans of the Julia Child and Jacques Pepin cooking duo and they like to cook and bake bread for each other, although more modestly than Julia and Jacques. They’ve slowed their social life down a bit, but being crazy about each other, they enjoy each other’s company and the slower pace is comfortable for them.

Guy Perito is a happy man and he looks forward each day to the challenges, chit-chat and drop-in visitors at Shoe Repair by Gaetano’s.

[Editor’s note: Guy Perito passed away on June 6, 2014. He was 93. ]

A 1941 Ford in Jamaica Plain

In 1952, I was making 50 cents an hour at C.B. Rogers’ drugstore and had saved some money. I bought a used 1941 Ford. It was dark blue. It was one of the last models that Ford made before WWII ended all American car production during those years. I paid $60 for it.

Painting by Peter O’Brien Copyright © 2015, All Rights Reserved. Click on the image to see it larger.

Painting by Peter O’Brien Copyright © 2015, All Rights Reserved. Click on the image to see it larger.

The dashboard was rusty so I painted it maroon and grey with house paint from Yumont’s Hardware store in Jamaica Plain. Yumont’s is still there. The passenger-side window was missing, so dates at the Dedham Drive-In movie theater were interesting. During snowfalls I put cardboard in the opening.

I learned that you could start a car by pushing it and letting the clutch out at the right moment. I did that a lot. Used cars were advertised in those days with, or without, R&H (radio and heater). I had the H but no R. A man at work sold me a radio from a 1936 Buick for $3 and I rigged it up under the dashboard and installed a coat-hanger antenna. It blew a lot of fuses though.

I put a rebuilt engine in the car after a year or so of breakdowns, black smoke pouring from the exhaust, and grinding noises. Precision Motor Rebuilders in Somerville did the work. I think it cost $295 plus my old engine. I don’t remember where I got the money.

The Ford became a communal car. Anyone in the gang could use it if they had gas money. Gas in those days cost 19 cents a gallon.

One day, several of us packed in and we went to Atlantic City. We barely had enough money for a ten-cent hot dog when we got there. Perhaps it was at Nathan’s. I don’t remember. We stayed overnight and slept under the boardwalk. The next day we came home on the Merritt Parkway in Connecticut and we had a flat. The State Police stopped to ask if we needed help. I said no. (I had changed a flat tire once before on the night I bought the car.) We nearly tipped the car over using the bumper jack on the steeply sloped embankment of Merritt Parkway. It was a fun trip though.

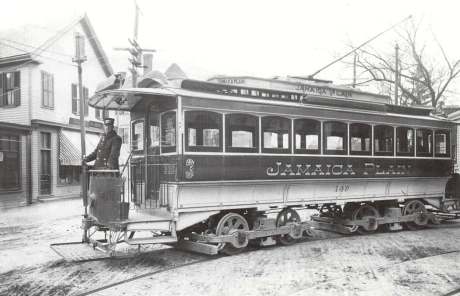

Before I had a car I went everywhere by streetcar. Some streetcars were parked in a terminal on South Street, up at the end of our McBride Street. McBride enters South on the right in the picture. The side-entrance streetcar on the far left is coming from the Arborway Terminal, heading into Boston. The two streetcars in the South Street Terminal went back and forth to Dudley Street in Roxbury. The streetcar cost five cents for students, and ten cents for others.

We called the South Street Terminal the “Car Barns,” because fifty years earlier a big barn housed the streetcars behind the billboard. However, its official name was the “Jamaica Plain Loop.” A carnival came every year to the former car barn lot. There’s a housing project there now. The Jamaica Plain Loop is long gone and the American Legion Post No. 76 and its flagpole have moved away too.

I joined the Army in 1954 and never saw the car again, until now.

Peter O’Brien

Copyright © 2015, All Rights Reserved

A German Tourist in 1916 Jamaica Plain

This is the story of a personally conducted tour through Jamaica Plain. It began about 6:45 last evening, and it lasted for about two and one half hours. And if there were any streets that escaped, it wasn’t the fault of patrolman Joseph Cunningham of Station 13, the conductor, or Mrs Louisa Cline of 16 Dixville St., South Boston, the conducted.

The tour began in this wise: Patrolman Cunningham was walking along Burroughs St. a few minutes before 7 o’clock when a woman rushed up. "Aber, wo ist das? —" and she trailed off into the mysteries of German. Patrolman Cunningham had left his German at home on the piano. After a desperate attempt he gathered that she was looking for 8 Amory St.

As she seemed at a loss, he decided to take her to the address. And just here the tour began. When the tourists got to 8 Amory St. they found that it was the wrong place. Patrolman Cunningham asked her who the people were she was to meet. She didn’t know. Then she had an inspiration. It wasn’t Amory St. after all. It was Burroughs St.

Back the party went. They hunted up 8 Burroughs St. No use; they were wrong again. Cunningham strove again to get the name of the person sought by Mrs. Cline. She couldn’t remember it. But she thought that the street might be Parkman St. The tour now turned to that highway, but there was no one at No 8. Certainly that wasn’t the place.

The next inspiration of the conducted was South St. By this time Patrolman Cunningham was getting his stride. The preliminary had been mere play. He decided that they would begin at the car barn and "do" every street in the vicinity. They did. And when it was all over, although the conductor was a willing guide, he decided that he had done his share of walking for about a month, so the tourists turned toward the police station.

Lt. Riordan was flabbergasted when the party arrived. Mrs. Cline overwhelmed him with a torrent of German. He hurried to the desk and rang for the sole German policeman in the station. But that gentleman was floored by Mrs. Cline as easily as the others.

Finally, after nearly 15 minutes questioning, Lt. Riordan managed to inform the conducted that she was not under arrest. He only wished to know where she lived. And as soon as he extracted that bit of information, he got busy with the telephone.

Twenty minutes later a man and woman entered the station. They were Mr. and Mrs. W. Heinmann of 8 Enfield St, Jamaica Plain. They were in a great to do. They had arranged to meet - "Ach, ya! Aber es ist das Enfield St." came an excited voice from the seat near the wall where Patrolman Cunningham and the conducted were seated. And then followed an excited and heart-gladdening greeting.

After the matter had been all straightened out, and the two ladies and Mr Heinmann had closed the door behind them and walked down the steps, Patrolman Cunningham stood up and scratched his head. "Well, I’ll be darned."

A Holocaust Survivor Returns to Jamaica Plain

How a chance meeting on JP’s Boylston Street reveals a Holocaust survivor’s brief connection with Jamaica Plain 80 years ago.

By Peter O’Brien, December, 2009

Ed looks out the window of 257 Lamartine St. in 1931A member of the Jamaica Plain Historical Society happened to be on Boylston Street in early November 2009 and, by chance, met a couple from Hastings on Hudson, New York, who were looking for a certain house on Lamartine Street. The couple, Edward Lessing and his wife Carla, were looking for the house at 257 Lamartine where Ed had lived in the early 1930s. After a short residence there, Ed Lessing’s story took many turns with several unplanned surprises including life-threatening experiences with the Nazis and his mother’s internment in a notorious concentration camp during World War II. This amazing story about a Dutch family displaced by the Holocaust and happily reunited after the war, might never have happened if the patriarch, a cellist, could have found work and remained in Jamaica Plain during those pre-war depression years.

Ed looks out the window of 257 Lamartine St. in 1931A member of the Jamaica Plain Historical Society happened to be on Boylston Street in early November 2009 and, by chance, met a couple from Hastings on Hudson, New York, who were looking for a certain house on Lamartine Street. The couple, Edward Lessing and his wife Carla, were looking for the house at 257 Lamartine where Ed had lived in the early 1930s. After a short residence there, Ed Lessing’s story took many turns with several unplanned surprises including life-threatening experiences with the Nazis and his mother’s internment in a notorious concentration camp during World War II. This amazing story about a Dutch family displaced by the Holocaust and happily reunited after the war, might never have happened if the patriarch, a cellist, could have found work and remained in Jamaica Plain during those pre-war depression years.

The Lessings Leave Holland Ed with his father in BostonThe story starts in 1929 when a Dutch Jewish couple, Nathan ‘Nardus’ Lessing, his wife Engeline ‘Lien’ Elizabeth, (nee van Leer,) and their three-year old son Eddie arrived in America. They were greeted by Lien’s sister, Suze and her husband David (Cohen) van Leer who had emigrated to the United States earlier and had settled in what was then the most Catholic (97%) city in the USA; Holyoke, Massachusetts. They tried fruitlessly to rent an apartment there until a friend told them that with a name like Cohen, they would never succeed. David and Suze then changed their name, legally, to van Leer and never thereafter told anyone that they were Jewish. David van Leer worked in a typography company while Suze worked as a bookkeeper. The van Leers never left Holyoke.

Ed with his father in BostonThe story starts in 1929 when a Dutch Jewish couple, Nathan ‘Nardus’ Lessing, his wife Engeline ‘Lien’ Elizabeth, (nee van Leer,) and their three-year old son Eddie arrived in America. They were greeted by Lien’s sister, Suze and her husband David (Cohen) van Leer who had emigrated to the United States earlier and had settled in what was then the most Catholic (97%) city in the USA; Holyoke, Massachusetts. They tried fruitlessly to rent an apartment there until a friend told them that with a name like Cohen, they would never succeed. David and Suze then changed their name, legally, to van Leer and never thereafter told anyone that they were Jewish. David van Leer worked in a typography company while Suze worked as a bookkeeper. The van Leers never left Holyoke.

A New Friend Tries To Help

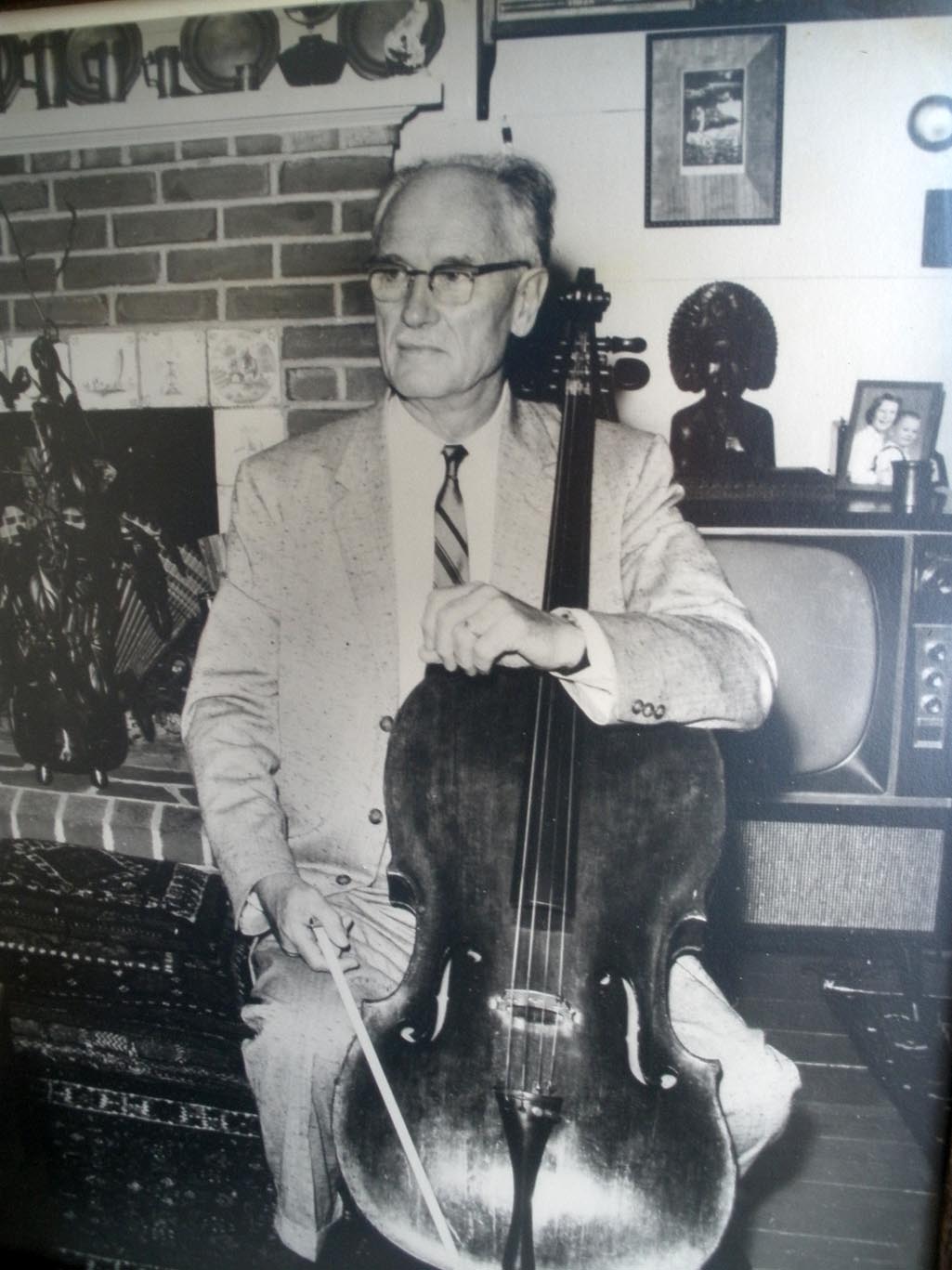

Nardus Lessing, an accomplished cellist, had studied at the Music Conservatory in The Hague, Netherlands, until his father told him that he had had enough education and he should now find a job in music somewhere. He was soon hired as a member of a musical trio on a ship that sailed for Cuba. He also made several working trips to New York on ships of the Holland-America Line. A few times he visited his sister-in-law Suze and husband David van Leer in Holyoke during his New York layovers. Jacobus Langendoen with celloWhen the family emigrated, Nardus had hoped to find steady work in America through Jacobus ‘Jaap’ Langendoen, a Dutch cellist with the Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO), which was then under the direction of Serge Koussevitzky (1924-1949). The family tradition is that Nardus may have met Jaap through his sister-in-law, Suze van Leer, of Holyoke. Langendoen at that time lived at 17 Pearl Street in Dorchester. Jaap’s granddaughter, Heidi Langendoen, of Wakefield, Massachusetts, fondly recalls her grandfather as someone who would try very hard to help another musician and that he mentored many young musicians over his long career. She remembers hearing about his summer work playing at the Wentworth Hotel in the town of New Castle, New Hampshire. Later, the Langendoen’s bought a house and resided there for many years.

Jacobus Langendoen with celloWhen the family emigrated, Nardus had hoped to find steady work in America through Jacobus ‘Jaap’ Langendoen, a Dutch cellist with the Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO), which was then under the direction of Serge Koussevitzky (1924-1949). The family tradition is that Nardus may have met Jaap through his sister-in-law, Suze van Leer, of Holyoke. Langendoen at that time lived at 17 Pearl Street in Dorchester. Jaap’s granddaughter, Heidi Langendoen, of Wakefield, Massachusetts, fondly recalls her grandfather as someone who would try very hard to help another musician and that he mentored many young musicians over his long career. She remembers hearing about his summer work playing at the Wentworth Hotel in the town of New Castle, New Hampshire. Later, the Langendoen’s bought a house and resided there for many years.

The kindly Jaap Langendoen will appear again after the war to help another member of the Lessing family.

Untimely Illness

Unfortunately, Jaap Langendoen’s helping hand could not be accepted because Nardus contracted tuberculosis and was hospitalized in Holyoke. There was a small 50-bed Holyoke City Sanatorium on Cherry Street, Holyoke, which had been under the direction of Dr. Carl Rosenbloom. The 1930 census lists Nathan Lessing and several other patients and staff as residents at the Holyoke City Sanatorium. In those days before effective TB drug therapy was developed in the early 50’s, patients’ recovery rates were not good.

Following this health disaster, Nardus’ wife, Lien, and their son Eddie, found themselves living in a two-family house at 257 Lamartine Street, Jamaica Plain.

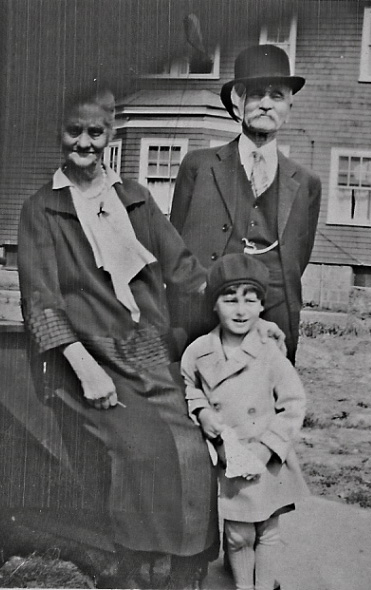

Only in America Ed’s ‘adopted’ grandparentsLien, a very enterprising former telegraph operator, first of all searched for and found an elderly couple to take care of Eddie during the daytime. Eddie fondly remembers them only as Grandma and Grandpa, a kindly couple whose surname cannot be recalled.

Ed’s ‘adopted’ grandparentsLien, a very enterprising former telegraph operator, first of all searched for and found an elderly couple to take care of Eddie during the daytime. Eddie fondly remembers them only as Grandma and Grandpa, a kindly couple whose surname cannot be recalled.

Lien then found employment with Mr. Ben Franklin Allen who owned a small travel bureau called “Allen Tours” on the second floor at 154-156 Boylston Street, Boston, a six-story building located across from Boston Common between Tremont and Charles Streets, in what is now the Piano Row Historic District. The first floor at 156 Boylston Street was occupied by the New England Piano Company. Ben Franklin Allen lived at 12 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston.

Ed Lessing clearly remembers Allen’s name because of an incident his mother related much later. It seems a former travel client sent a letter addressed to Mr. Allen at “Allen Tours.” Lien opened it and it read: “Dear Mr. Allen, - I do not know anyone whom I hate enough to let him suffer one of your tours! Sincerely etc.” Lien, torn between duty and fear of an executive outburst finally got up the courage to hand the offending letter to Mr. Allen. As she said years later, “I could not believe what happened. Mr. Allen read the letter twice, then burst out in uncontrollable laughter and shouted, ‘The best letter I ever received. Let’s frame it!’ And so it was done, and Mr. Allen proudly hung it over his own desk.” Eddie always remembered this story as proof that there was no country in the world like America where such a thing could happen!

Health Restored

In 1931, in what was a very lucky outcome for the period, Nardus recovered. He then found summer work through Jaap Langendoen, as a cellist with 11 other members of the BSO, at the grand Wentworth Hotel in New Castle, New Hampshire.  BSO group at Wentworth in 1931The family moved to New Hampshire and enjoyed a happy summer there while that music engagement lasted, remaining hopeful that a more permanent job in music could be found. Ed Lessing’s photographs from that memorable summer show him playing in the water with his mom. Nearly 80 years later, on their way to a conference in Boston, Ed and Carla Lessing stayed at the same Wentworth Hotel and presented them with a picture of those summer of ‘31 musicians, which included Ed’s dad, Nardus Lessing.

BSO group at Wentworth in 1931The family moved to New Hampshire and enjoyed a happy summer there while that music engagement lasted, remaining hopeful that a more permanent job in music could be found. Ed Lessing’s photographs from that memorable summer show him playing in the water with his mom. Nearly 80 years later, on their way to a conference in Boston, Ed and Carla Lessing stayed at the same Wentworth Hotel and presented them with a picture of those summer of ‘31 musicians, which included Ed’s dad, Nardus Lessing.

As the depression deepened permanent work could not be found, and in 1932, three years after their arrival, and with only the summer work at Wentworth Hotel and Lien’s job at Allen Tours having sustained them, the Lessings had to return to the Netherlands.

Back Home in Holland

After their return, the Lessings finally settled in the small historical town of Delft, located near Rotterdam. Delft is noted as a most typical Dutch town with a canal passing right through the town center. It was the home of the noted painter, Johannes Vermeer and the world-famous Delft pottery.

The Lessings, struggling through the depression at whatever work that could be found, had three more sons, one of whom died at nine months.

World War II Arrives in Holland

By May 1940, the Lessing family of Nardus, Lien, Eddie (14), Arthur ‘At’ (6) and Alfred ‘Fred’ (4) had become part of the community living on the canal in Delft. At that time Hitler’s troops overran Holland’s little democracy and installed a Nazi government there led by a friend of the Führer, The Reichskommissar for the Occupied Dutch Territories, Dr. Seyss Inquart, who was hanged after the war as a war criminal.

As a non-religious, though, nevertheless, a Jewish family, the Lessings found themselves in immediate danger. It took the Nazis just three years in Holland to accomplish what they did in their own country in six years, i.e. to destroy the age-old Jewish communities by murdering its members, irrespective of age or gender, in death camps located in Nazi-occupied Poland.

Nardus and Lien saw that the only way to survive with their three boys was to go into hiding from the Gestapo, the Secret German Police. Thus, on October 22, 1942, the Lessings dispersed and disappeared.  Ed with his mother in New Hampshire in 1931At that point, Eddie’s mother, Engeline Elizabeth Lessing/van Leer changed from housewife to heroine, fighting to save the lives of her entire family. First, she secured a false ID card with a new name from the Dutch Resistance. She then began to travel through Holland with the false ID on the extremely dangerous, constantly Gestapo-patrolled trains to find hiding places for her sons, her husband and herself.

Ed with his mother in New Hampshire in 1931At that point, Eddie’s mother, Engeline Elizabeth Lessing/van Leer changed from housewife to heroine, fighting to save the lives of her entire family. First, she secured a false ID card with a new name from the Dutch Resistance. She then began to travel through Holland with the false ID on the extremely dangerous, constantly Gestapo-patrolled trains to find hiding places for her sons, her husband and herself.

At great personal risk, she succeeded in placing all in fairly secure locations with trusted Dutch families. Lien and Nardus were taken in by a brave gentile family who hid them for two years. As the war wore on, however, Lien had to find new safe houses for her younger sons Fred, aged six, and At, aged eight.

Rescued From the Nazis

Her eldest son, Eddie, 17, wound up with a group of Dutch Resistance men in their headquarters hut in the woods in the center of Holland, near the tiny village of De Lage Vuursche, in the Dutch province of Utrecht. At dawn on December 29, 1943, German forces arrived to arrest and/or kill the Resistance group. Eddie was standing watch at the time and he and his partner barely had time to warn the six men sleeping in the hut and save themselves. The men quickly dressed and scattered into the forest.

As part of a contingency plan in the event of such a raid, at eight o’clock that evening, Eddie and his partner went to a designated meeting place in the woods, about seven miles from the hut, where they hoped to meet any survivors of that morning’s raid. At the meeting place they were armed with 9mm Mauser pistols in case of a surprise German attack. Soon, in the pitch-black darkness, someone arrived on a bicycle. Fearing that it was a German trap, Eddie and his friend held their fire. And they were thankful they didn’t shoot when they discovered that it was neither the survivors of the raid on the hut nor German troops that had arrived, but to their astonishment, the bicyclist was found to be Eddie’s mother, Lien!

Lien explained to Eddie that as soon as she heard about the raid on the hut, she “immediately decided to try and rescue you.” She then explained that they were completely surrounded by a large circle of Wehrmacht and SS troops looking for them and that they should immediately bury their weapons to avoid being killed when arrested.

When the weapons were buried, Eddie’s partner accepted Lien’s bicycle and flashlight and left to find a hiding place leaving Eddie and Lien standing in the dark, surrounded by Germans. At this moment, Lien conceived a desperate plan to survive as they walked towards the encircling German troops waiting to capture them. They soon came to a German soldier pacing with a shouldered rifle and immediately executed Lien’s plan. Tightly hugging each other in an embrace with heads close together they began talking and laughing loudly, while making kissing sounds. As they approached the German soldier, they waved to him with a wide smile on their faces and ice-cold fear in their hearts. He stopped them with a loud HALT! - - - and they kept the grins on their faces as he made up his mind. It was at that moment a life or death decision for the two of them. Suddenly he shouted, “Nah also, gehen sie!” (Now then, get going) as he waved them on. They thanked him profusely with many loud “Danke schons” (thank you’s) and thus they walked out of that circle of death to live another day.

Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp Ed (standing right) with Leni Langendoen (in the background)In May 1944, Lien was on her way to find a new hiding place for her youngest child, Fred, when she ran into a Gestapo specialist on a Dutch train. He immediately recognized her false ID card and she was arrested. She was put in a separate train compartment with a civilian Dutch police officer to guard her on her way to Gestapo Headquarters in Amsterdam. Realizing that she had all the family members’ hiding-place addresses in her handbag, she surreptitiously tore each piece of paper in shreds, chewed it up and swallowed it, to arrive in front of the Gestapo interrogators with only her false ID card.

Ed (standing right) with Leni Langendoen (in the background)In May 1944, Lien was on her way to find a new hiding place for her youngest child, Fred, when she ran into a Gestapo specialist on a Dutch train. He immediately recognized her false ID card and she was arrested. She was put in a separate train compartment with a civilian Dutch police officer to guard her on her way to Gestapo Headquarters in Amsterdam. Realizing that she had all the family members’ hiding-place addresses in her handbag, she surreptitiously tore each piece of paper in shreds, chewed it up and swallowed it, to arrive in front of the Gestapo interrogators with only her false ID card.

“Who are you?” she was asked. “I am Engeline Elizabeth van Leer”

“Do you have a husband?” “Yes, he is in the U.S. Merchant Marine.”

“Do you have children?” “No, I have no children.” And then, out of the blue, she shouted, “You have no right to keep me here. I am an American citizen!”

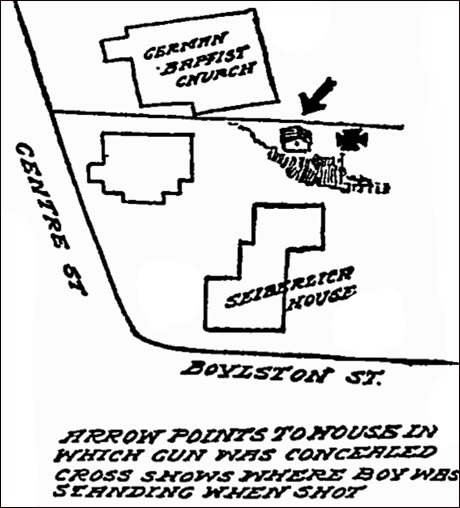

The Gestapo agent, having heard every Jewish excuse to prevent their imprisonment or death, asked her the next question: “Well, Mrs. van Leer, if you are, as you claim, an American citizen, you have, no doubt, no problem giving us an address where you have lived or where your husband lives in the United States?” And she, with unfailing memory of 1931, answers the Gestapo interrogators: “No, I have no problem - - 257 Lamartine Street, Jamaica Plain, Boston, Massachusetts.”

As the interrogator wrote down her response, Lien heard a German officer behind her saying, “Well, that’s no fake, she knows where she lives.” Nevertheless, she was eventually sent to the infamous Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in northern Germany where she managed to barely stay alive by getting a night job in a kitchen where she could sometimes steal half a potato.

Then, one morning in January 1945, returning at dawn to her barracks, she is told by her bunk-friend to present herself to an SS officer who is checking on people with foreign nationalities. “Why?” she asks. “You told them you are an American,” her friend answered. Lien responded, “You know, I just made it up,” but her friend nevertheless urged her on and Lien presented herself to the SS guard. He checked a list and told her that in two days she’d be on a transport out of the camp, to be exchanged for a German citizen.

Two days later, with 300 other sick and dying prisoners of Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, she was put on a train that traveled to St. Gallen, a border town in northeastern Switzerland, where they were exchanged; ironically, for Germans coming from Palestine where they had been interned as enemies by the British.

Lien chose not to go to her sister Suze in America, but rather to stay in a United Nations Rehabilitation camp, winding up in Camp Jeanne d’Arc, in Algiers on the North African coast.

When the war finally ended, Lien hitchhiked a ride on an American bomber and was reunited with Nardus, Ed, At and Fred once again in Delft.

Starting Again in America

Soon after the war, the Lessings again immigrated to America. All except 21 year old Ed, settled in Springfield, Massachusetts, where Nardus taught cello, Lien became a buyer in a hardware store, and Ed’s brothers At and Fred attended college; both becoming professors of philosophy.

Ed’s brother, At, however, had earlier considered a career in music and actually took cello lessons for a year from none other than Jaap Langendoen! At recalls that every Sunday he would take the bus to Newton Upper Falls and have his lesson from Jaap who was expert in the bowing of the cello and the instrument’s technical demands. Jaap’s wife, Leni, would then serve a hearty lunch for the three of them. Jaap would then head for his BSO matinee and drop At off at the bus station. On the way, At would ask Jaap what music was to be played that afternoon and Jaap would reply, “I’ll find out when I get there!”

Continuing his help to the Lessings, Jaap Langendoen got At a full summer scholarship in 1954 to study with the BSO at Tanglewood where Leonard Bernstein was conductor of the student orchestra. However, realizing that music was not to be his life’s work, At began a new life that fall and went on to study at Wesleyan. He never stopped playing the cello, however, and to this day uses finger warm-up techniques taught him by his respected mentor, Jaap Langendoen.

Ed Lessing pursued a career as an independent graphics designer and is now retired. He devotes much of his time to lecturing and writing about the Holocaust. He occasionally finds time to build a WWII model airplane.

Ed’s Dutch wife, Carla, also survived the Holocaust. In 1942, at age 12, she began to live as a “hidden child” in Nazi occupied Holland. The hidden children were the Jewish kids whose parents chose to place them anywhere survival was even remotely possible. These children lived for extended periods with kind (and sometimes not-so-kind) host families, in convents and churches, in barns, attics, caves, cellars and even in sewers to escape the Nazis searching for people to send to the labor and death camps. All who would rescue these terrified children and their families were themselves at risk of death or deportation for harboring them. Carla spent years moving to and from hiding places in Holland and despite several stressful close-calls she survived to meet and marry Ed Lessing and come to America with him after the war. Her memories, as with many of the hidden children, are very painful, confusing and rife with carried-over anxieties and fears. With the background of these life experiences she became a caring and effective psychotherapist and an active officer of the Hidden Children Foundation/ADL, a New York-based survivor’s group. Ed Lessing, 2009Over the intervening years Eddie has often wondered what became of the men in the hut and especially his partner who rode off into the night on his mother’s bicycle. Fifty years later he was to learn that all the hut’s occupants, including two downed Royal Air Force airmen, had escaped. One of the airmen, Fred Sutherland, a full Cree Indian, was a crew member of the famous RAF Squadron 617 bomber group known as the “Dam Busters.” And, contrary to Eddie’s long-standing memory of the partner being a certain resistance fighter who was later killed by the Nazis, the actual partner was in fact alive and serving as a Catholic Bishop in New Guinea! Ed was reunited with Bishop Herman Munninghoff in Holland in 1992 where the Bishop recounted the exact same version of the terrifying night of the raid on the little hut in the woods, his own dangerous escape on Lien’s bicycle and his later calling to the priesthood … all thanks to Eddie’s mom.

Ed Lessing, 2009Over the intervening years Eddie has often wondered what became of the men in the hut and especially his partner who rode off into the night on his mother’s bicycle. Fifty years later he was to learn that all the hut’s occupants, including two downed Royal Air Force airmen, had escaped. One of the airmen, Fred Sutherland, a full Cree Indian, was a crew member of the famous RAF Squadron 617 bomber group known as the “Dam Busters.” And, contrary to Eddie’s long-standing memory of the partner being a certain resistance fighter who was later killed by the Nazis, the actual partner was in fact alive and serving as a Catholic Bishop in New Guinea! Ed was reunited with Bishop Herman Munninghoff in Holland in 1992 where the Bishop recounted the exact same version of the terrifying night of the raid on the little hut in the woods, his own dangerous escape on Lien’s bicycle and his later calling to the priesthood … all thanks to Eddie’s mom.

The Lessing’s dramatic stories of evading the Nazis and surviving the Holocaust as children, hiding alone or with host families in occupied Holland, are told in the book “The Hidden Children – The Secret Survivors of the Holocaust” by Jane Marks.

Ed and Carla live in Hastings on Hudson, New York. They have two children; Noa, born in Israel and Dan born in the United States and four grandchildren.

Epilogue 257 Lamartine, 2009While many of us were collecting paper and scrap metal, and buying war bonds and stamps to win the war, a nimble-minded Dutch mom was outwitting her Nazi captors and surviving one of the most notorious concentration camps to become an exchanged prisoner and thus live to see her family reunited after the horror called the Holocaust.

257 Lamartine, 2009While many of us were collecting paper and scrap metal, and buying war bonds and stamps to win the war, a nimble-minded Dutch mom was outwitting her Nazi captors and surviving one of the most notorious concentration camps to become an exchanged prisoner and thus live to see her family reunited after the horror called the Holocaust.

And, had a kind-hearted attempt to find music work for her husband (who never served as a Merchant Mariner except as a cruise ship musician) by Jacobus “Jaap” Langendoen succeeded back in 1930, 257 Lamartine Street might only be remembered today as just another Jamaica Plain two-decker instead of an important landmark in the world of a courageous Dutch family.

Sources and References:

Sheldon Rotenberg, retired Boston Symphony Orchestra violinist, Brookline MA

Heidi Langendoen, Jacobus Langendoen’s granddaughter,Wakefield MA

Bridget Carr, Boston Symphony Orchestra Archivist

Books:

“The Boston Symphony Orchestra, 1881-1931” by Mark Anthony DeWolfe Howe, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1931

“Gentlemen, More Dolce Please” by Harry Ellis Dickson, Boston: Beacon Press, 1969

“I had put all that behind me years ago” copyright monograph by Edward Lessing, 1994

“The Hidden Children – The Secret Survivors of the Holocaust” by Jane Marks, New York: Ballantine Books, 1993

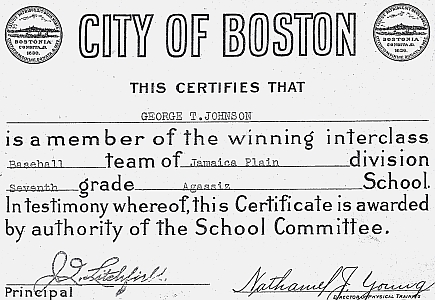

Agassiz School Notes - 1922 to 1929

The idea of recording these memories came in a discussion with Agassiz teacher, Marilyn Walsh. She said that there seemed to be no history of the Agassiz Schools as they were before they moved from Burroughs Street down to Carolina Avenue. I decided that if I did not write these thoughts down nobody would. Actually, I took one or two copies of the School Magazine called The Agassiz Boy to the Headmaster there sometime three or four decades ago. As I recall it, it was when the School was still on Burroughs Street. I also think I gave them the third grade pictures. Perhaps they are in the library on Holbrook Street.

The idea of recording these memories came in a discussion with Agassiz teacher, Marilyn Walsh. She said that there seemed to be no history of the Agassiz Schools as they were before they moved from Burroughs Street down to Carolina Avenue. I decided that if I did not write these thoughts down nobody would. Actually, I took one or two copies of the School Magazine called The Agassiz Boy to the Headmaster there sometime three or four decades ago. As I recall it, it was when the School was still on Burroughs Street. I also think I gave them the third grade pictures. Perhaps they are in the library on Holbrook Street.

Kindergarten

On a bright day in early September, 1922, Mother took me by the hand from 6 Newsome Park, down Eliot Street to Brewer, down Brewer to Burroughs and up the granite steps into the smaller of the two brick Agassiz School buildings. She took me to put me into the kindergarten, which was in the room on the first floor on the right, as you went through the door on the Burroughs Street side of the school. I was a somewhat protected child, they having waited 5-1/2 years for me after my brother was born, and I did not like the idea of staying there all day, but there was not anything I could do about it. The ice was broken for everybody when poor little Calliope Jairis vomited. She was the daughter of the able fruit storeowner across from the bank and two or three stores from Seaverns Avenue on Centre Street. She obviously was more upset than I. Everything settled down when very large, round white haired custodian Kelley came in with a bucket of sawdust and cleaned the whole thing up.

I do not remember very much about kindergarten except that our teacher was Miss Earnshaw. If I have it correct, the Earnshaws owned and operated an old “coaching inn” on Center Street, West Roxbury, just beyond the current Unitarian Church. The inn was razed three or four decades ago to build a Stop & Shop or one of those markets. I believe it was still functioning as a tearoom during those years.

My father, having been on a championship club baseball team in the 1890’s in Boston was terribly pleased that I had Miss Earnshaw, for, if I remember correctly, her brother pitched either for the New York Yankees or New York Giants.

I do remember that we sat in a circle in that room. The circle was painted red on a maple floor. I suppose we sang all the songs and did all the things that kindergarteners do.

The Buildings

Actually there were three buildings. The use of the plural in the title was done on purpose. The Primary School contained the first three grades. It was a red brick Victorian building with a double-pitched roof, slate, as I recall it. It was very high studded. The basement had windows above the ground. In the basement were the latrines. The boy’s room had a slate barrier and trough with water running down the slate. Some small boys tried to shoot over the barrier and did occasionally, until a supervising teacher interfered. I never saw the girl’s bathroom.

The larger of the two buildings was built probably around 1880 or 1885, some twenty years later than the Primary School. There were several buildings like the Primary School around, such as the Hillside School on Elm Street on the corner of Everett Street at the end of Seaverns Avenue. It was razed for a parking lot across from the Congregational Church. I believe these schools were built shortly after the annexation of Roxbury by Boston in the1860’s.

This larger of the two schools was truly Victorian. It had a large overhang. Its main grand entrance was on Brewer Street. The Headmaster’s office was over the grand entrance looking out on Brewer Street toward Jamaica Pond. There was a protrusion on the primary school side which contained the fourth grade which I attended. I believe the architectural reason for the protrusion was to allow the hall on the third floor to take all the pupils.

Despite the fact that the main entrance was on Brewer Street, we entered and excited through the Burroughs Street side. Directly across the street from the entrance was a wonderful penny-candy store where one could buy “tootsie rolls” or other luscious items. It was in the workshop of the local house painter, Mr. Heap.

There was a third building in the back of the brick courtyard sort of between the two brick buildings, but way back toward Thomas Street. This was a gray prefabricated school building. Several prefabricated buildings were added during that period as the number of pupils increased. It was probably either a Hodgson Houses or a Brooks Skinner prefabricated school, one floor, and I believe heated by a stove.

First Grade

The first grade was on the second floor on the back side toward Thomas Street. The teacher, whom I had, was Miss Cleveland. She was a graying rather large woman who wore glasses. I have a couple of recollections of that class. That is where we started cursive writing the Palmer Method, “push and pull,” but with pencil. I think we did not get ink until the second grade, or even the third grade.

We learned to spell with a box of little green letters out of which we would pick the right letter. Once I saw the exact letter that I wanted on the desk of a fellow pupil across the aisle. As I reached over to get it, Miss Cleveland just had to say loudly “David.” She was a nice person, and all went smoothly.

I believe it was that year that we became very conscious of Miss Anna Von Groll, who was the Assistant Principal of the Primary School. One day my mother came to pick me up early for a doctor’s appointment and Mother never got over the fact Miss Van Groll pinned her up against the wall of the stair hall and scolded her, asking her what she thought she was doing breaking up the continuity of the School by picking me up for a doctor’s appointment at quarter of twelve when school did not close until twelve. Much more on this Miss Van Groll later.

Second Grade

For the second grade we went up to the top floor on the back toward Thomas Street. The class was broken in two and someone else had the room on the Burroughs Street side. My teacher was Miss Bertsch. She happened to be the sister of the stenographer in my father’s office in Roxbury. I do not know whether that helped or hurt. She was very tall, probably 5’11”. Had a somewhat large nose, was graying by this time. As I remember it, second grade was a serene year except for the fire escape.

Naturally, we had to have fire drills. These came unannounced. We would go out a door directly from the room onto the grill of the fire escape. Unfortunately, instead of looking down at the step, one looked right through to the brick courtyard below.

Perhaps it is well that we had practiced, because one morning about eleven o’clock the fire alarm went off and we all thought it was a false alarm. When we got down to the ground and out the gate on the other side, there was Engine 28 and the other pumpers. We were told by all the authorities to get out of there and go home.

My father was something of a “spark” having witnessed the Roxbury fire as a little boy in the 1880’s, which burned down the old Walpole Street American League baseball grounds on the site of where Northeastern exists today. He also witnessed the Chelsea fire a few years later. When he heard that the School was on fire, when I got home, as he happened to be there, he got into the car and took us to see what was happening. It actually was a fire and the firemen were on the roof taking the slates off and chopping through the roof. I believe we went back to school the next day.

Third Grade

Third grade under Miss Van Groll was really something. She probably stood all of 4’10” or 11”. She was a little round. She had brown hair and wore pince-nez glasses, as I recall. She was a little autocrat, as is indicated in the episode with Mother and the doctor’s appointment.

When she would sit at her upright piano and play back to the class, she would announce that she could see everything that was going on in the polished mahogany of the piano, so we must behave.

One of her finest moments was probably in 1926, the day after Malcolm Nichols was elected as the Mayor of the City of Boston. His son, Clark Nichols, was in my grade. The new Mayor came and visited us the day after he was elected. I can still see him now in a black Chesterfield, a gray suit, black shoes and a derby. Miss Von Groll was thrilled that he had come to her class.

The Nichols’ lived on Centre Street on the corner of Hathaway Street. There was a younger brother and sister. Mayor Nichols was a widower at the time, I believe.

I do not remember the names of too many people of that grade, but I can say that Dorothy Neale was very bright and may have been the brightest in the class. Another very bright boy was Hugh Gray. I remember also Pricilla Picket, who was the daughter of the eminent carpenter in Jamaica Plain, who lived off Centre Street near Dunster Road. Jane Ohler lived on Orchard Street and we often walked to school together and became good friends as grownups. One of the Bowditches, I think Hoel, came down from their place on top of Moss Hill. Philip Rasmussen, later a Navel Flier hero, lived as far away as Winchester Road. The school at the end of Louder’s Lane had not been built yet. Henry Schmidt lived right at the entrance of Louder’s Lane. Those were the people I saw because of growing up on Prince Street walking to school.

However, most of the children came from the other side of Centre Street from Lamartine Street and Chestnut Avenue and down Centre Street toward St. Thomas Aquinas and Carolina Avenue, Custer Street and so forth.

I think the second section of the third grade was in the portable building. I do not know how they divided us, whether it was by grades or just arbitrarily. I believe the other second grade teacher was a Miss McReady.

Then in the fall of 1926 we split. The girls went to the Bowditch School and the boys went next door to the larger Agassiz School building.

Fourth Grade

My fourth grade teacher was Mrs. Holland. She was a lovely lady with white hair. She was kind and soft spoken and everybody took to her. My friend Nathaniel J. Young, who still lives on Pond Street, Jamaica Plain, tells me that at that time a married person could not be a teacher. His mother had been a teacher in the Boston School system until she married Mr. Young. I believe Mrs. Holland was a widow and lived on Willow Street, West Roxbury. She was a nice enough so that my parents sought her out one afternoon and that is why I have the Willow Street recollections.

Later, according to Joan Scolponeti whose father was Corporate Council at City Hall and who grew up on May Street, Jamaica Plain across the street from the Gargans, with whom she played, told me that she also had Mrs. Holland. So sometime in the years after I left, the fourth through eighth grade building apparently started to accommodate girls as well as boys.

The Ruling Hierarchy

We have already noted that Miss Anna Von Groll, who proudly lived at the Fritz Carlton Hotel on Boylston Street near Fire Department Headquarters, was the Assistant Principal of the Primary School.

The Headmaster of the whole Agassiz School system was Joshua Q. Litchfield. “Q.” stood for “Quincy.” Mr. Litchfield was extremely proud of his Yankee ancestry and of that Quincy name which, after all, was related to the famous Adams family in Quincy. He looked like a typical Yankee, bald, with a large nose. He seemed completely competent to handle the job.

Under him the Assistant Headmaster, who was a receding-chin gentleman by the name of James Nolan. Everybody thought “Jimmy” Nolan as tough. It was he who gave the rattan to the worst offenders (more on this later). In case Mr. Nolan was out, Miss West, who was also somewhat chinless, had the authority. She was an eighth grade teacher.

Fifth Grade

My fifth grade teacher was a round somewhat red faced, brown haired 35-year-old called Miss McGowan. She was a very good teacher. She was a very good disciplinarian. It was there that the rattan first appeared. Luckily I escaped it. It was fearsome to see these tough little boys asked to go into the coat room to get their hands whacked with a rattan and come back with tears running down their faces and all defiance gone.

For a short time that year Miss McGowan was sick. She was replaced by a younger woman by the name of Miss Butler. She must have had a boy friend at Boston College, because all she could talk about was the Philomatheia Club. I looked in the Newton phone book but the Philomatheia does not show. I have seen it in a Swiss Chalet style building over there. I suspect that Miss Butler attended dances or parties at the club there in the 1920’s.

It was in the fifth grade that we started woodworking. I got good grades at Agassiz, all “1”s in everything except woodworking. The more dexterous boys were sent down to Eliot School on Eliot Street, which had been taken over by the Public School System sometime in the 19th century. There they really got good woodworking training. I think our woodworking teacher’s name was Mr. Maguire. He was very patient with clumsy people like me, and in spite of not getting a good mark, I enjoyed it and still tinker with things.

Sixth Grade

For sixth grade we went upstairs to the second floor of the big building. The teacher was Miss Childs. The other sixth grade teacher I do not remember. The School did go on through the eighth grade at that time. After age 11 I had more confidence. I would stay after school and play with John Malone, who lived on Brewer Street, in the schoolyard until thrown out. Malone’s father had the Arborway garage on Centre Street near Forest Hills. Originally before automobiles, it was Malone & Keene with horses and buggies. Or I even went down to the Carolina playground and tried playing baseball, but I was not any good, so gave it up.

The next year I went off to Roxbury Latin.

Movies

Once a month or so we would go upstairs to the third floor where Mr. Litchfield would give us a treat of movies. Of course, these were silent movies and captioned. This was supposed to be a treat, however, getting two or three hundred little unclean boys in a hot hall is not the pleasantest for the olfactory senses.

The Children’s Museum

At that time the Children’s Museum was located on the Pine Bank of Jamaica Pond in the Victorian mansion of Thomas Handasyd Perkins, which is still there, although it is falling apart. We would walk from the school down approximately to Mayor Curley’s mansion and there would be a policeman there who would get us across the traffic. These visits went completely over my head, but I guess some of the children got something out of it. The Children’s Museum moved to the old Mitton Mansion on the corner of Burroughs Street and the Jamaica Way before it moved downtown a few years ago.

The Pet Show

In the spring of my sixth grade year, it was announced that there would be a pet show on the lawn across the street from Mayor Curley’s house on a given Saturday. Our family had a thoroughbred wire-haired fox terrier. I bathed her, and primped her, and brushed her, and put a ribbon on her and walked down there to the site of the show. I looked around and it did not look to me as though I had much competition. There were two or three cats, a couple of not very beautiful dogs. Perhaps there was a canary, a parrot.

Just when the teacher said, “We will now have the judging,” the door of Mayor Curley’s Mansion opened and young Francis came out. The policeman stopped the traffic, led him across the street and with his not-very-well-groomed mongrel dog. This was just in time for the judging.

The teacher called him by name and told him to come and we could now have the judging.

My recollection is that I did get the Blue Ribbon, and Francis Curley got second prize, a Red Ribbon.

Summation

This was a very good school, the Agassiz School. These teachers were good. They devoted their lives to teaching small children. All of them were unmarried except Mrs. Holland, who was a widow, as I said. Most of them had been trained at Boston Normal School on Huntington Avenue. Discipline was strong.

There was a great mixture of people in the Agassiz School. As I described before, most of the pupils came from the south side of Centre Street. This was not an affluent area. One little boy needed a bath so badly that one of the teachers sat him in the back of the room so that the odor would not bother the other children (or the teacher).

Joe Graham was a genial, smiling, blonde policeman, who got those two to three hundred children across Centre Street safely every day. He was a character. He was there long after I left school.

On a balance, it was a good and fulfilling experience.

Written by David A. Mittell.

David A. Mittell grew up on Prince Street in Jamaica Plain. He attended the Agassiz School and Roxbury Latin. He is a 1939 graduate of Harvard University. Mr. Mittell is a retired executive of Davenport Peters, the oldest American continually operating lumber wholesaler. He is a member of the board of trustees of the Plimoth Plantation and Roxbury Latin High School.

—

Comment by George B. Stebbins, Jr. (geosteb at juno.com):

A friendly amendment: I believe the policeman who covered Centre Street was Joe Graham, not Jimmy. Jim Graham, who lived in the castle on the Arborway, was president of the Forest Hills Cooperative Bank. I also attended the Seeger School where the Mittell and Salisbury names were important; I spent four years at Agassiz, two at J. P. Manning, and then went to Roxbury Latin School.

Copyright © Jamaica Plain Historical Society.

Alleged Wagon Thieves Arrested

Find Booty at Jamaica Plain.

Shoemaker is Charged with Receiving Stolen Goods.

Driver Escapes from 11 Headquarters Men.

A revolver shot, fired in the air by Inspector Lynch in front of 3110 Washington St., Jamaica Plain, yesterday afternoon, drew ten other inspectors of Police Headquarters from hiding places and gave the signal for the arrest of three men.

The men arrested are charged by the police with being responsible for the disappearance of two wagons filled with leather, satin and shoes. The moveable part of the alleged booty was brought to Police Headquarters last evening where it now occupies the entire floor space of a good-sized room.

Patrick J. Culhane, aged 22, no home, who was released from State Prison only a few months ago, after serving a sentence for larceny of a similar nature, was one of the men. He and Charles Sidney are charged by the police with larceny. Sidney is 20 years old. He also disclaims a place of resi-dence.

Samuel Stone, aged 41, a Jamaica Plain shoemaker, who lives at 8 School St. and has a place of business at 3140 Washington St., Jamaica Plain, was the third man arrested. He is charged with receiving stolen goods.

In the mix up attendant upon the rush of the arresting officers following the revolver signal, a fourth man, driver of a wagon upon which the two alleged thieves rode to the scene of their cap-ture, escaped.

According to the police, Culhane and Sidney would stroll along the streets until they came across a well-laden wagon, the driver of which was not nearby. They would jump upon the wagon and drive off. The police charge that Stone, the shoemaker, received the goods thus stolen.

For several days and nights a headquarters inspector has been in hiding near the shoemaker’s shop, watching and listening. Yesterday morning a tip reached Police Headquarters, and the eleven in-spectors were sent out to Jamaica Plain.

It was arranged that Inspector Lynch should remain on the street and fire the revolver as a signal, while the other offices, to avoid suspicion, should hide themselves nearby. Inspectors Smith, Sheehan, Laughlan, Dennissey, Burke, Morrissey, Egan, Dorsey, Concannon and Kilday, whom Chief Inspector McGarr had assigned to the case, accordingly got out of sight.

Very soon a wagon drove down Washington St. and stopped before 3140. Culhane and Sidney, according to the police, were on the wagon. As the wagon came to a stop they were having a bit of horse play between themselves. Incidentally the police say they changed caps.

It is said that when the wagon stopped, Stone came from his shop and placed a bundle of leather on the wagon. Then Inspector Lynch fired his revolver and the ten inspectors appeared.

Inspectors Sheehan and Dorsey grabbed Stone before he could move. Culhane and Sidney started to run away, but Inspectors Smith and Morrisey gave chase. Inspector Smith caught Sidney and Inspector Morrisey got Culhane.

They were brought to Headquarters, when it is said Culhane was identified by Inspector Michael H. Cronin as the man he arrested about six years ago by overturning the wagon upon which he and another man was riding. At that time it was alleged that Culhane attempted to kill Inspector Cronin by firing a revolver at him. Culhane was tried for this. He was sent to state prison.

The inspectors also brought to Headquarters a couple of wagon loads of stuff said to have been stolen by Culhane and Sidney. Great cases of shoes formed the best part of the alleged loot, but there were numerous other things as well, including mops, paper and satin.

Culhane and Sidney are officially charged by the police with the larceny on September 9, from Whipple & Co., of 311 South St., of a horse and wagon, six bundles of leather, 1 bundle of satin, 314 pairs of shoes, five gross of shoe laces and one roll of paper, all valued at $1700. They are al-so charged with the larceny from A. Towle and Co. of 41 Matthews St., of a horse and wagon and seven bundles of leather valued at $1000.

Awakened by the Joyous Sound of Bells

The coal was in the cellar, a barrel of flour in the pantry, preserves and piccalilli stored away, plenty of beans for baking, a good supply of winter vegetables and you were all set for the winter.

The coal was in the cellar, a barrel of flour in the pantry, preserves and piccalilli stored away, plenty of beans for baking, a good supply of winter vegetables and you were all set for the winter.

Then one morning you would be awakened by the joyous sound of bells. To children this meant one thing - IT SNOWED! The pungs were out! (a pung is a low one-horse sleigh) First to announce the good news were the milkmen who started their deliveries before five o’clock in the morning. The horses had special shoes for the winter, which had, caulks driven into them - sharp pieces of steel which would give a gripping power in the snow and ice. Each night after the days work the horses hooves were checked to see if the caulks had become dull. If so, they had to be replaced.

At the first storm of the year, if it were accompanied by severe cold or wind, the horse would be sporting his winter shoes, a warm woolen blanket and the bells, which would announce his coming. He was “rarin’ to go” with half the schoolchildren of the neighborhood running alongside him. Hopping the pungs on the way to school was a way of life for children in Jamaica Plain, It annoyed some of the drivers but most of them, remembering their own childhood, either closed their eyes or just made sure you were on safely. It was great fun!

All was great for the horses as long as they were on level ground, but there were hills, which were difficult to go up, and, when they were iced, were more difficult to come down. Vividly I remember an icy day when a horse fell on Newbern Street, broke his leg and had to be shot. Also, if there was a thaw the main streets would become bare in spots and it would be a very difficult drag for the horses. However, the milkmen know the angles and would use the side streets as much as possible. The Public Works Department in Jamaica Plain was located on Child and South Streets where the Farnsworth House and equipment needed to carry on public works. Snow removal, as we know it today was not a problem. Mother Nature would take care of it in time. Huge weighted drums six feet in diameter and eight to ten feet in width were drawn by teams of horses through the streets after a storm. The roller left the street hard packed with snow over which teams of horses pulled pungs on snow runners.

A horse and small V plough with a driver took care of the sidewalks and made them passable for pedestrians. Children who had no fear of horses whatsoever found them a formidable sight when they invaded the sidewalk. They were given the right of way as the children watched from the safety of their yards.

After the First World War, the automobile and the truck came into their own, and the days of the horse, wagon and sleigh were almost gone. Snow removal then became a problem and the people were required by law to shovel the snow from their sidewalks. This applied to both property owners and tenants as well. If there was a delay in clearing your sidewalk the police would be at your door to read the law to you. As a general rule those who were fortunate enough to have a car would put it into the barn or garage for the months of January, February and March until the roads were usable for tires again. This continued until the 1940’s when a car became a must for the year round.

For children there was much to do in the winter. There were great hills that were safe for coasting; skating on Jamaica Pond, and the playground at Child and Carolina Avenue was flooded for skating as well. The girls built snowmen and women and dressed them up in whatever they could come up with. The boys built snow forts and piled up a heap of snowballs, and from the safety of the fort went to war with their adversary. There was, indeed, great fun in the simple things of life in those days!

Sources: Gerry McCarthy, McCarthy Brothers Milk Company; B. Tafty, 1001 Questions Answered About Storms.

Written By Mary Glynn. Reprinted from From the Archives, Winter 1989, a newsletter once published by the Archive Committee of the Jamaica Plain Historical Society. Copyright © 1989-2003 Jamaica Plain Historical Society. Photograph courtesy of Chicago Historical Society, Chicago Daily News negatives collection, DN-0090242.

Blessed Sacrament Corner Stone Laid

This article originally appeared in the September 29, 1913 edition of the Boston Daily Globe. Production assistance provided by Kate Markopoulos.

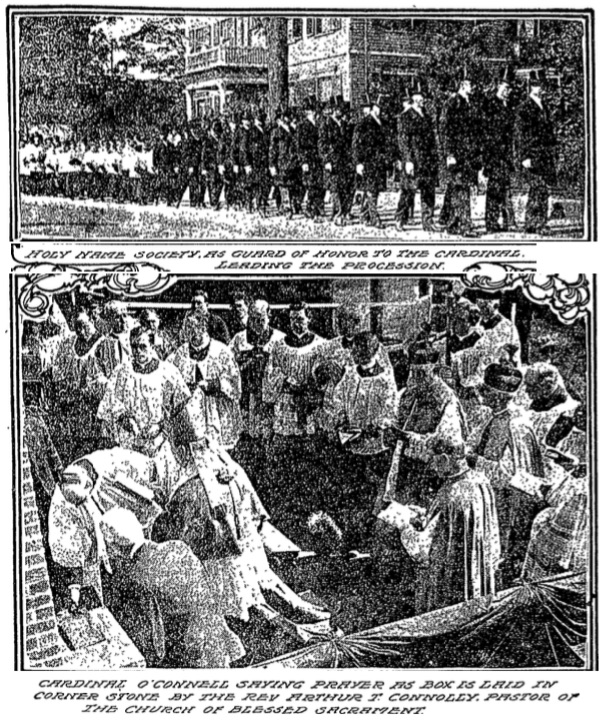

Cardinal O’Connell at noon yesterday laid the cornerstone of the new Church of the Blessed Sacrament in process of construction on Center near Creighton St., Jamaica Plain. Nearly 5000 present and past parishioners, many of whom had assembled early in the forenoon, attended the interesting ceremony which followed the last mass of the day in the present church.

His Eminence brought up the rear of an impressive procession of monsignori, clergy, and laymen from the rectory to the church, including about 500 of the parish Holy Name Society, Captain Joseph Dugan, and about 300 of the Knights of the Blessed Sacrament. They were followed by Rev. Frederick J. Allchin of St Paul’s Church, Dorchester, as crossbearer, leading the following monsignori and parish priests: Mgr. M. J. Splaine of the Cathedral, Mgr. Edward J. Moriarty, PR, of St Thomas’ Church, Jamaica Plain; Mgr. P. J. Supple of St John’s Church, Roxbury; Rt. Rev. Denis J. O’Farrell of St. Francis de Sales’ Church, Roxbury; President Thomas I. Gasson, SJ, of Boston College; Rev. Dr. Edmund T. Shanahan of the Catholic University, Washington; Rev. M. T. McManus of Brookline, Rev. James B. Troy of St Vincent’s Church, South Boston; Rev. James J. O’Brien of Somerville, Rev. James Lee of Revere, Rev. D.J. Wholey of St. Joseph’s Church, Roxbury; Rev. Charles Regan of All Saints’ Church, Roxbury; Rev. James J. Hayes, CSSR, of the Mission Church; Rev. George Lyons of the Church of Our Lady of Lourdes, Jamaica Plain; Rev. Fabian O’Connell of East Boston, Rev. Frederick J. Allchin of St. Paul’s, Rev. Joseph Brandley of Neponset, Rev. Irving Gifford of Cambridge, Rev. Arthur T. Connolly, Rev. Joseph P. Maher, Rev. Edmund Daly and Rev. John F. Madden, all of the Church of the Blessed Sacrament.

A large chorus of children sang, under direction of Fr. Daly, as the Cardinal was escorted to his throne, Mgrs. Moriarty and O’Farrell were chaplains to His Eminence. The sermon was preached by Rev. Dr Edmund T. Shanahan, a Jamaica Plain boy, now a professor of dogmatic theology at the Catholic University, Washington. Fr. Shanahan’s sermon was on the Christian doctrine of life in contrast to the economic theories of the day, which the speaker characterized as partial, one-sided and exclusive. “The Catholic doctrine of education, progress and life,” he said, “is that of total, complete self-development, mental, moral, physical, social and religious.

“In this magnificent sweep of view the Catholic doctrine of life is superior to all others, as the whole is to its parts. It includes all the good of modern movement for the physical betterment of man, resisting only the anti-Christian theories of life with which, unfortunately and unnecessarily, science and social work are too often associated nowadays. “Some single-barreled thinkers of the day have wrongly got it into their heads that the service of God is somehow opposed to the service of humanity. This is a gross misunderstanding of elementary Christian doctrine.

“The service of man is one of the appointed ways and means of serving God. The latter service includes the former, as a wheel within a wheel. It is not a question of two things, but one thing in two relations. The future Altruria of the Socialist, where others alone shall reap what we are now sowing, is not an ideal capable of setting the souls of men afire with the spark of self-sacrifice. Self-sacrifice is not an end in itself, but a means to an end, and modern social preachers have made a fatal blunder in asking men of flesh and blood, ambition and self-interest to sacrifice themselves for such impersonal abstractions as the race, the community, the greatest good of the greatest number.

“Man needs reality, the personal God of justice and mercy, to live for and to worship. No merely human gospel of neighborliness will ever prove our efficient substitute for the unmutilated gospel of Christ. A religion of humanity can never take the place of the religion of God.” During the sermon Dr. Shanahan paid a warm tribute to Fr Connolly, not only for the success of his work as administrator, but also for the exceptionally fine, practical, commercial education which he has provided for the children of the parish.

Cardinal O’Connell made a brief address, observing: “Surely Boston ought to be a city of peace and order. From every hill for miles around gleams the sacred sign of our redemption, the cross which teaches man that here there is no lasting happiness except the contentment of virtue and religion. May this new citadel be to the whole city, as well as to those who live in its shadow, a tower of holy strength and a pledge of God’s benediction upon this good and beautiful city.”

The procession marched to the corner stone, which was laid by His Eminence with a silver trowel which will be presented to the most liberal contributor to the new church. The Cardinal was assisted by many priests, prominent among whom was Rev. Arthur T. Connolly, the pastor, who placed within the stone a copper box with documents, newspapers, coins, photographs and a list of the contributors to the special corner stone collection a year ago.

Bob's Spa