George W. Fowle’s Recollections of 19th Century Jamaica Plain

Published in the Boston Daily Globe on July 12, 1908

Histories record facts, furnish dates, and tell the cause and effect of changes and progressions, political and otherwise, but to feel the underlying sentiment of past times, to acquire that close personal touch with persons and events, you must read what men of those times have written; or, better still, if you can, talk with men ripe in years, who can give you first hand, from their own knowledge and reminiscence, the human touches, the little details which are crowded out of histories.

If, instead of being satisfied with simply reading American history and thereby getting, at best, a sort of distant look at past events and people, you would be made to feel a closer relationship and a truer familiarity with those events and people, you must talk with a man like George W. Fowle of Jamaica Plain, who as a child was held in Lafayette’s arms; who knew William Lloyd Garrison and saw him mobbed in the streets of Boston; who later stood with Garrison at the corner of Washington and State Streets and saw the first regiment of colored soldiers go off to the war; who saw Wilkes Booth standing back of his house in Jamaica Plain three days before Lincoln was shot; whose father knew and helped John Howard Payne; whose brother knew and worked under Admiral Foote and heard him give General Grant encouragement and advice at the beginning of the war; whose mother died on the day that George Washington passed away; whose memory, in short, teems with interesting facts of history.

Mr. Fowle, although 87 last Thursday, is as active as a man of middle years. Not a faculty is impaired. His eye is keen, his hearing as acute and his mind as alert as ever, and in talking of happenings of many years ago his memory never fails him.

He has always taken a deep interest in the affairs of the country and its people and thus is able to easily call to mind a host of incidents large and small. And it is a source of great pleasure to him to reflect upon events which have happened since his memory began.

Mr. Fowle comes of the sturdiest of New England stock, and he claims relationship with all the Fowles in the country. “The only family of Fowles which came across,” he explains, “were four brothers who landed back in 1600 and something.

“One settled in Woburn, one in Connecticut and the others in Virginia, and from these boys sprang the families of Fowles here now. One of those who went to Virginia married into the Custis family, one daughter of which was the wife of George Washington.

“I was born in New York and when I was but a baby our family moved to Westfield, which is at the extreme westerly end of the state, on Lake Erie. My father’s mission in going there was to establish a customhouse for the U.S. Government to handle goods that were coming over from Canada. While working there in the government service he organized a military company and as its head was quite a factor in the town.

“While we were there, that was in 1824, Lafayette made his second visit to this country, and, as you’ve read, was feted generally. His mission here, of course, was to be present at the laying of the cornerstone of Bunker Hill Monument. While here, Congress voted him $200,000 and a large piece of land in Ohio, and being naturally curious to have a look at his land he traveled by the old stage coaches to the west, or what was then considered the west, passing through Westfield on the way. It became necessary for him to stop there a day or two and he was given a royal reception.

“I was but three then, but my mother used to discourse frequently on the affair afterward, so that it seems as though I have a recollection of it all my own. My father as head of the militia company helped arrange for the reception, which included an elaborate ball in the evening.

Held by Lafayette

“Lafayette, who, by the way, was extremely fond of dancing, had the first dance with my mother. The next night there was another reception, and many women and children were there, and then Lafayette showed his love of children. I was one of those whom he picked up and held while he joked and laughed with the mothers.

“A few years later we returned to New York, and one of the things that happened while we lived there that left a most vivid impression upon my mind was the epidemic of cholera which spread from England through New York down into Central America. It was terrible in New York that summer, and I can remember now the death teams going by loaded with bodies. I was about eight then.

“While in New York my father used to make trips abroad, Tunis being one of the ports he touched. One day, about four days before he was to sail, a man came up and asked him the cost of a trip to Tunis. My father told him, and the man’s reply was that it would take all the money he had and leave him nothing after he got there, so my father offered to let him live on the boat after they reached there.

“The next night my father and the man were walking along the street and stopped in front of a house to hear a woman playing a musical instrument and singing. One of the songs was ‘Home Sweet Home’ and as the woman finished singing it the man turned to my father and said ‘I wonder what the woman would say if she knew the author of that piece was standing out here listening to it?’

“When my father had found words to express his astonishment at learning who his companion was, Payne explained that it was his song and how he came to write it.

Payne Tells How He Wrote “Home Sweet Home”

” ’ There were four of us boys,’ he said, ‘who were accustomed to meet in the eating saloon, and one night while there someone suggested that each try to write a song about home. We all sat there and scribbled away, and what that woman has just sung was the result.’ Payne was afterward appointed Consul to Tunis and I have a couple of letters at home now that he wrote my father while he was there.

“I had in my possession for many years the only flag with the original 13 stars and 13 stripes in the country. About two years ago I gave it to the State and it is now hanging in the State House. Soon after Congress decided on that pattern of flag my grandfather had one made and hung it from the old homestead.

“Upon his death it was handed down to my father and later to me. The old homestead where it first hung is 150 years old, and still standing on Amory Street near Hogs Bridge. The flag is at least 125 years old. The late Admiral Sampson, while at the Charlestown Navy Yard, heard of the flag and came out to see it.

“When I spread it out before him he said: ‘We are trying to put the old Constitution in such a condition that she will last for many years, and when we get her improvements completed we must have a gala day on board and raise this flag on her, even if for a day.’ This pretty plan was never carried out, because the Admiral’s death came soon afterward.

“Some of my choicest recollections are of William Lloyd Garrison, that noble hearted Abolitionist, and I am indebted to a kindly fate that threw me in with him frequently. I first saw him on the day that he was mobbed in the streets of Boston.

“I happened to be walking down State Street and saw a crowd ahead of me, and as I reached Washington Street saw a mob in front of the office of the Liberator, Garrison’s paper. I got there just after he had been taken into the Old State House, which was then City Hall, for protection.

“The crowd tore down the sign over Garrison’s office, and if I had only realized what important history was then being made I would have saved a piece of the sign which I picked from the ruins and carried around half the day for company.

“Well, I walked through the great yelling mob from the Liberator office to City Hall, and as I reached there Mayor Lyman opened a window and began to address the crowd. I saw Garrison standing beside him. The Mayor appealed to the crowd in the interest of fairness and peace.

“The crowd still hung around waiting for Garrison to come out, and they were nearly outwitted too. I happened to walk around on Wilson’s Lane, which is now Devonshire Street, and saw Garrison being bundled into a carriage, having come out on the other side of the building.

“Just as the carriage was getting away the crowd realized what was happening and they attacked it, trying to cut the harness from the horse, etc. The driver was nervy and determined, however, and he slashed right and left with his whip and drove through that dense crowd.

“Those were exciting times, I tell you. They carried Garrison that day to the old Leverett Street jail. That was in the fall of 1835.

Garrison at Work

“I was a bookbinder, and although the doctors had told me I must keep out of doors all the time, and had been doing so for some time, I decided to buy a shop next to Garrison’s office, and I staid there about a year.

“One night when I came into my office I found a book lying on my desk which one of my workmen had left there, marked for Mr. Garrison and to be delivered that night. I was alone in my office, so I took the book up myself. I rapped on Mr. Garrison’s door and was bidden to enter. As I went into his printing office I saw him at his desk, alone in the shop, working like mad.

“We talked a few minutes and I remarked that he was staying late, to which he replied: ‘I’ve got to get my paper out in the morning. I’m writing an editorial now and when I get it finished I’ll set it up over there and then print it myself. I can’t afford to hire much help, and if I can’t get help I will do the whole thing myself.’

“It wasn’t so much what Garrison happened to say to me that night, but it was the way he said it; it was his whole bearing and the cast and expression of his countenance that told me that he was carving a niche in history. He was in the midst of his terrible struggle and there were yet many dark days ahead of him.

“About 25 years later I was standing at the corner of State and Washington Streets watching the first colored regiment that the north sent to the war, march to their boat. Robert Gould Shaw was at their head, and they marched, as they knew they were marching, to complete annihilation. The work of such men as Garrison was nearly over. They had fought against immense odds for years, night and day, and were watching a cruel war finish their labors.

“As I stood there watching that noble, self-sacrificing Shaw lead those Negroes away, I happened to turn my head and saw Garrison standing beside me. His eyes filled with tears, as he, too, watched the colored troops pass by.

“I spoke to him and asked him if he remembered that day so many years ago when he had stood by the side of Mayor Lyman in the window just over our heads, and he nodded. ‘Yes’ he said. ‘I well remember that day, and many others that have gone since. Our fight has been a long one and the fight those fellows are going into is to be a hard one, for not one of them will come back alive.

” ‘I’m sorry for those poor fellows, for I know just what will happen to them when they get down there,’ and worn and bent with the constant struggle of years, Garrison walked away. I later visited him at his home in Roxbury and he introduced me to his two sons, who are still living, as one of the ‘boys who was in his mob.’

Booth in Boston

“One morning in April 1865, while walking across the land in back of my house I saw two men standing on a pile of rocks that stood on some raised land back of mine. One of them raised his hand in salute and spoke to me, and I recognized my neighbor, Benjamin T. Stevenson. I returned his greeting and went on about my business. Three days later we were all astounded by the news that Lincoln had been assassinated.

“That day I met my neighbor Stevenson and as we talked over the grave situation he said to me: ‘Fowle, do you recall seeing me talking with a man back of your house three days ago?’ I told him that I did. ‘Well,’ said Stevenson, slowly and soberly, ‘that man was Wilkes Booth.’

“I could scarcely restrain my astonishment, and Stevenson went on to explain that on the night before I had seen him with Booth they both had been present at a gathering in Brookline, which was attended by a number of people - a social gathering it was, I believe. When the time came to leave, Booth told Stevenson that he was going to get back to Washington and was in a hurry to see about some mining interests of his.

“My neighbor said that there was no use in starting out at that time of night, and asked him to come to Jamaica Plain and spend the night with him. Booth accepted the invitation, and in the morning they walked out a piece from the house to look about.

“During all the time that Booth was in my neighbor’s company he never mentioned Lincoln, the war, or any of the prevailing troubles, and Stevenson could not believe that Booth, his guest, and Booth, the murderer, were one and the same.”

Thus did the old gentleman regale the reporter, who paid a birthday visit to him, with tales of the past. Nor were these all, for he told many more, not yet exhausting his fund of recollections. And he enjoyed telling them as much as the reporter enjoyed hearing them all.

He has a house full of interesting mementoes of the past, and his brother John and his wife are the proud possessors of like reminders. Another brother, Samuel A. Fowle, who lives in Arlington, was also in Washington at the time of the war, and can recount facts of time gone by. Samuel made medals while in Washington, which the soldiers wore in battle.

Mr. Fowle lives at 214 Chestnut Ave., Jamaica Plain, with his son’s family. His wife died about three years ago. When his father came east from New York they lived on Fort Hill. He learned the printing and bookbinding trade and went to Woburn and opened an office.

Mr. Fowle is a well-known figure in Jamaica Plain, respected by everyone. He is Deacon in the Boylston Congregational Church, and three years ago was tendered a reception by the Society in observance of his residence of half a century in the District. He has been treasurer of the Horticultural Society and Vice President of the Davis Street Home.

Production assistance and transcription by Peter O’Brien.

Growing Up in a JP Three-Decker in the 1950s and 1960s

by Roy Magnuson 171 Forest Hills Street. 1957 Courtesy of Roy MagnusonI spent the first year of my life in a three-decker at 20 Glade Avenue, a dead-end street off Glen Road near Franklin Park. On my first birthday in May, 1950 we moved to the third floor of a three-decker at 171 Forest Hills Street. My grandparents were the owners and lived on the second floor with my widowed aunt. Life on the third floor had its ups and downs, literally, but I look back on it with many fond memories.

171 Forest Hills Street. 1957 Courtesy of Roy MagnusonI spent the first year of my life in a three-decker at 20 Glade Avenue, a dead-end street off Glen Road near Franklin Park. On my first birthday in May, 1950 we moved to the third floor of a three-decker at 171 Forest Hills Street. My grandparents were the owners and lived on the second floor with my widowed aunt. Life on the third floor had its ups and downs, literally, but I look back on it with many fond memories.

One big issue was the heat. Not enough of it in winter, and too much of it in summer. Until about 1964 our main source of heat in winter was a coal-fired boiler in the cellar that fed steam radiators in our apartment. This system required constant attention and many trips down and up three flights of stairs every day to stay warm.

Each summer a delivery truck would bring several tons of coke, not coal, and deposit it into our cellar storage bin using a chute through a cellar window. I never understood why, but my father preferred coke over coal. Although he used to talk about the dangers of coal gas, I’m guessing that coke was cheaper.

The big decision each fall was when to fire up the boiler. Too early in the fall might mean using up coke when it wasn’t really necessary; too late in the fall might mean not having heat when we really needed it. When it got cold out, we really needed it.

When the big day came, it took a bit of work to get the boiler going. First we’d crumple up lots of newspaper and throw it in the boiler. Then came the kindling: lots of small pieces of wood; then bigger pieces of wood on top of that. Next, in went several lit wooden matches. The object was to get a good, strong wood fire going that produced a nice bed of red glowing coals. (Dad was always on the lookout for wood. When the old utility pole was replaced out front, he got the workers to leave it in our driveway. He spent many hours sawing and splitting it up.) After about a half hour, two shovels of coke went on top, the draft was adjusted, the fingers were crossed, and if everything went as planned, the coke caught, glowed bright red, and we had heat. But before the steam made its way up to our radiators we had the banging.

There was some kind of problem with the steam pipes that fed the radiators on the living room end of our apartment. Every time the heat “came up” we heard this loud bang-clang-bang-clang. It sounded like someone was hitting the pipes with a hammer. But the noise passed in less than 30 seconds, then came the blissful sound of the radiators hissing. That meant heat. Finally! No amount of fiddling with the involved radiators by lifting this end or that end or both ends could ever stop the banging. We learned to just live with it.

Every day in winter Dad made many trips down to the cellar to add coke, adjust the draft, shake down the ashes, shovel out the ashes, add more coke, dislodge a clinker, etc. Then in the early 1960s we converted to oil. That was just awesome. From that point on, when we got cold all we had to do was turn a thermostat on the dining room wall and after a while the pipes banged, the radiators hissed, and we got warm without having to go down to the cellar at all. What an improvement!

In summer we had the opposite problem: too much heat. All day the sun would shine down on the flat roof and bake our apartment. It got really hot. The kitchen at suppertime would often get unbearable. What saved us was our screened front porch. It faced east so it got no sun after noon. We spent many hours out there every summer trying to escape the heat. In 1965 my mom got a part time job at Diamond’s Dress Shop on Centre Street. Right from the beginning she must have saved every dime she made because before long she bought two small air conditioners, one for each bedroom, so we could sleep when it was hot. We were among the first in the neighborhood to have an air conditioner, and what a difference they made. Over the years Mom also worked at Jones Gift Shop, Wayne’s Clothing Store, and Eileen’s Women’s Store.

The Stack

Before we converted to oil heat, our hot water came from a device in the kitchen called “the stack.” This thing was a cylindrical black gas-fired water heater that sat alongside the kitchen stove. It connected to a copper storage tank in a small closet. When we needed hot water we opened the stack’s door, lit a match, turned on the gas valve which ignited a good sized flame, then closed the door. If we just needed to wash the supper dishes, we only let it run a few minutes. We’d open the closet door and feel the top of the storage tank. If it was hot down several inches, that meant we had enough hot water for the dishes. But if we needed to take a bath (we had no shower), it had to run longer. We needed the top two feet of the tank to be hot to make sure we had enough hot water to fill the tub. We were always reminded to never forget to turn off the stack, because it could explode. The stack was not vented to the outside, which was fine in the winter because it warmed up the kitchen. In the summer it just made the kitchen even more unbearably hot. And it was dangerous because it could be extremely hot on the outside if it had just been running, but you couldn’t tell by looking at it. I learned to just stay away from it. It was removed when we converted to oil heat, which gave us “continuous hot water.” Good riddance.

The Neighborhood

Ours was the end three-decker in a row of eight three-deckers along Forest Hills Street. There were eight more around the corner on Lourdes Avenue, which also had three six-family houses. That’s a total of 66 apartments in a fairly small neighborhood. Each three-decker was owner occupied, and all were well maintained with an obvious pride of ownership. The neighborhood was very stable. Most families had been there a long time which meant you got to know your neighbors. All these apartments meant that there were plenty of kids to play with. When I was in grammar school, I had to go out to play every day unless it was raining. So did the other kids. We came home from school, changed our clothes, and then went out to play. We had to stay out until we were called for supper.

We found things to do because we had to. We played tag, hide-and-seek, red light, baseball, football. We threw rocks, rode bikes, climbed trees, went coasting in winter, collected horse chestnuts. We lived near the back edge of Franklin Park so we went exploring in the woods. On many Sunday afternoons in summer, my dad and I would walk through the Franklin Park woods and then walk alongside the golf course up to the Refectory across from the Zoo entrance. Dad would have a beer. I’d have a Coke. After a pleasant rest we’d walk back home. We’d often see people riding through the park on horseback. There were stables at the end of Forest Hills Street where anyone could go to rent a horse and ride through the park. Franklin Park was a wonderful and beautiful place to have so close to home.

Home Delivery

Looking back, it’s hard to believe that so many things were delivered right to our door. The ice man had already vanished by the 1950s, but many other delivery men still came around. Our milkman was Walter Collyer from Hood’s Milk. He came three times each week: Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. He delivered to each floor in our house. We got homogenized milk but my grandparents got the milk with the cream on top. They’d pour off the cream to use in their coffee. I’ve often wondered how many flights of stairs Mr. Collyer trudged up and down every day. Whiting’s milk also delivered to the neighborhood, but my mother preferred Hood’s. We had an egg man who came from his farm in Abington every Friday with a fresh dozen eggs for us and a dozen for my grandparents downstairs. Cushman’s bakery also delivered fresh bread.

A fruit and vegetable man came around yelling from his truck so the housewives would know he arrived. “Bananas! Strawberries! Fresh tomatoes!” You walked down to him so you could see what he was offering that day and check the freshness of his goods. A ragman came around every other week or so, yelling: “Rags. Got any rags?” He had a horse-drawn wagon, even in the 1950s. The insurance man, Eddie, came around each week knocking on doors and collecting the weekly payments due on people’s policies. In summer Bob the ice cream man came around every day ringing his bell. It sounded like the bell at school that told you recess was over. He had a small red pickup truck with a white ice cream freezer in back. When he’d open the freezer door to get your popsicle a cloud of white vapor would spill out and go straight down to the ground. He’d wait around a bit to give everyone time to run home, get a nickel, and run back. Numerous newspapers were delivered: The Globe, The Herald, The Traveler, The Record, and The American. Around Christmas we got two mail deliveries each day.

My School

I attended the Margaret Fuller elementary school on Glen Road from kindergarten in 1954 through the 6th grade in 1961, as my older sister had. My teachers were: Miss Jennings (kindergarten), Miss Pezzulo (first grade), Miss Heffernan (second grade), Miss Madden (third grade), Miss Macavella (fourth grade), Miss Loughran (fifth grade), Miss Shaughnessy (sixth grade). My sister had the exact same teachers seven years earlier.

My classmates (to the best of my recollection) were: John Callahan, Gail Collyer, Paul Cotter, Christopher Diminico, Joyce Duggan, John Fonseca, Robert Gava, Robert Grimes, Angela Hart, Edith Healy, Gary Kobialka, Dennis Magee, Linda Malovich, Edwin Mankiewicz, Mary Mulvey, Vicky Munafo, Judith Nawrocki, Angelina Nawrocki, Horace Ryder, Nancy Sardella, Evelyn Sargent, Judith Scapinski, Joseph Scarcella, Deborah Smith, Marcelle St. Clair, Joseph Tringali, Bruce Walker, Donald Watson, William Wetterhahn, Mary Wieziski. (Note: I may have unintentionally omitted someone or misspelled a name; it’s been a long time.)

Public Transportation

One reason why JP was a great place to live was the public transportation. All our lives we rode buses, trolleys, and the El. Right below Green Street Station we could catch the Wren Street bus that would take us up to the business district and all the stores along Centre Street. From there we could take the trolley and get anywhere along Centre and South Streets, as well as South Huntington and Huntington Avenues, all the way to Park Street station. The elevated Orange Line stopped at Green Street station, and went directly downtown to all the movie theatres, stores, restaurants and everything else in the city. By the time we were 12 or so, we often took the El to “Friend/Union” station. Then we’d walk under the Central Artery, through the North End, down to the municipal swimming pools on Commercial Street and spend the day swimming and having fun. We’d also go to “Milk/State” station, change to the Blue Line, and go to Revere Beach for the day. We could go places and do things by ourselves at a fairly young age, which, in retrospect, fostered our sense of independence and self-reliance. And we never once had a bad experience or a problem of any kind. Remarkable.

We were always trying to make some money. We’d run errands, cut the grass, shovel snow; anything to make a quarter or two. I spent many hours with my red Radio Flyer wagon combing the streets, woods, vacant lots, anywhere I might find returnable bottles. The small ones were two cents and the big ones were five cents.

I got my first real job just as I turned 14 at the Green Street Drug Store at the corner of Washington Street and Glen Road. I worked the soda fountain, and sold cigarettes, newspapers, candy and gum. Cigarettes were 28 cents a pack, and we sold a lot of them. I think everybody in JP was a smoker. The drug store was owned by Bob and Birdie Rosenberg. I worked for the summer but had to quit when school started. About 15 years later I met Bob and Birdie in Framingham. They had closed the drugstore and Bob had early stage dementia. What a shame. About a year later I started working across the street at the White City Food Store. I worked every day after school and every Saturday waiting on customers and making deliveries. I worked 19-1/2 hours each week and received a twenty dollar bill each Saturday. I worked there for about one year, then went next door to Strachman’s Cleaners. I also worked there after school and Saturdays and received $1.25 per hour.

The intersection of Washington Street and Green Street/Glen Road also had Timmons Liquor Store, a First National Food Store, Ruggerio’s Variety Store, a barber shop, and Jo-Anne’s Coffee Shop. With all the foot traffic from the El and the bus, it was a busy place. Jamaica Plain was just a great place to grow up. I left in 1974 when I got married and moved to West Roxbury. I look back fondly to my experiences there in the 50s and 60s, and I have many, many pleasant memories. I consider myself very fortunate to have lived there.

You may contact Roy Magnuson at:

Growing Up in Jamaica Plain by Jim Cradock

His cousin, Jerry Burke, who for many years was the owner of Doyle’s Café and is a local political and historical pundit, furnished the following memoir by retired Judge James Cradock.

Judge Cradock was born in 1941 and grew up on the upper end of Montebello Road near Franklin Park. He attended Our Lady of Lourdes School, Boston College High School and Boston College, where he graduated in 1963. After college he served on active duty with the U.S. Navy from 1963 to 1968. He continued his military service in the Naval Reserves and eventually retired with the rank of Captain.

Following his active military service Judge Cradock completed Law School at Suffolk University in 1970 and practiced law until 1990. At that time he was appointed a Judge of Federal Administrative Law, serving in various locations until his retirement in 2004.

Judge Cradock now lives in South Carolina and is a frequent visitor to Jamaica Plain where many of his relatives still reside. When I was about 14 or 15 and a student at B.C. High during the 1950’s two schoolmates and I decided to go to a football game at White Stadium in Franklin Park. After school we rode the T from Dorchester over to Egleston Square and walked from there up to the game. On the way we stopped at my house on Montebello Road where my mother gave us milk and cookies. As we left and started walking up to the stadium one of the boys, Frank Carney from Cambridge, said, “Gee, your mother has a beautiful Irish brogue.” I responded, “What do you mean?” I wanted to punch him in the nose! I didn’t of course and Frank became a lifelong friend who reminds me occasionally that he informed me that I was Irish that day. Hah!

When I was about 14 or 15 and a student at B.C. High during the 1950’s two schoolmates and I decided to go to a football game at White Stadium in Franklin Park. After school we rode the T from Dorchester over to Egleston Square and walked from there up to the game. On the way we stopped at my house on Montebello Road where my mother gave us milk and cookies. As we left and started walking up to the stadium one of the boys, Frank Carney from Cambridge, said, “Gee, your mother has a beautiful Irish brogue.” I responded, “What do you mean?” I wanted to punch him in the nose! I didn’t of course and Frank became a lifelong friend who reminds me occasionally that he informed me that I was Irish that day. Hah!

The truth is I didn’t believe my mother had any kind of accent. She did indeed have a beautiful brogue, as did my father, both having come from Galway. But their speech to me was as natural as the sun in the morning. This “Irish ear” which I had was reinforced regularly in the neighborhood I lived in.

Montebello Road in Jamaica Plain starts at Walnut Ave., which serves as a border to Franklin Park. It runs from there down a steep hill in our time gladed by leafy maple and oak across Washington Street and there under the El where Forest Hills Street comes in at an angle about halfway between then Green Street and Egleston T stations. From there it continues down, where it was known as “little Montebello” and reaches its terminus at the Our Lady of Lourdes complex of church, convent, school, rectory and old church.

At the intersection on Washington was kind of a mini-mall with Walter Leong’s Laundry, Gordon’s Market and Madden’s Drug Store on one side, and Johnny McLaughlin’s Parkview Spa (our “corner”—several people had run the store prior to Johnny over the years but he was the most recent and best known by our crowd), Mr. Dwyer the cobbler and Buddy Shea the Funeral Director’s office on the other. Across Washington was Johnny Hughes’ venerable Gas Station. At these places immediate necessities were often bought. I remember it being a big thing to me to be sent down the hill from 81 Montebello to the corner for “a quart of milk and a loaf of bread” and later to Gordon’s, where there was always sawdust on the oiled hardwood floor, for “a piece of cube steak.” I remember coming home with the Record-American one time, with a headline saying that Babe Ruth had died.

We had gas lanterns on Montebello that looked Dickensian era and ancient streetcars on Washington that looked from not long after. They were slow enough for some kids to hitch a ride on the back (not us). Washington Street was still cobblestoned then, making cars sound like tenor drums as they rolled along.

Above Washington was “big Montebello” and starting above Pop Martin’s Rest Home at about number 70 and going up to the 100’s there were about 15 three-deckers, counting both sides. Families who lived in them at one time or another during the 40’s and 50’s included the Careys, O’Connors, Tonrys, Keegans, Kellihers, Sullivans, Connaughtons, Conlons, Powers, Gradys, Laffeys, Clohertys, Matthews, Collins, Griffins, Coffeys, Tighes, Cradocks, and Mrs.Peasley. In almost every one of these families there was at least one “beautiful Irish brogue.” Thus we kids who grew up there at that time were graced every day, in our own homes and others, by that lyrical speech, “smiling eyes” and ready sense of humor with a hair-trigger willingness to laugh.

I estimate there were 20-30 of us growing up there then, all shapes, sizes and ages. It was one group, with the older taking care of the younger. I was reminded of it years later when my daughter Kathleen was on a swim team in Fairfax, Virginia which consisted of boys and girls, ages 8 (and under) to 18, where they all found community pulling together. When we were small the older girls looked after us. My brother Butch and I had the benefit of four older sisters, Mary, Patsy, Helen and Chris, and some of their friends like Joan Power, Marie Grady and “Reety” Conlon. Our cousin Noreen Dooley also lived with us then, having come over from Ireland when she was 10.

I remember Mary in particular, the oldest, looking after us. She and sometimes Patsy would bring us over to the beach at Savin Hill. We went to Revere Beach with Chris, and with Helen and her friend Helen Carey. I remember in later years groups of us, boys and girls, would take the excursion across the city to Revere. One time Charlie Cloherty, “the Punch,” got stuck in the folding side door of a streetcar on the way and let the driver know in a vocal way to “close the d—- door”. Since almost none of our families had a car we relied on the T for any traveling. We rode it all the time and it was very ordinary for us. Wasn’t something we ever complained about. The girls would walk us up to the park often, and it was always a treat to go to the Zoo.

Chris, our youngest sister, is and was four years older than me and seemed to get stuck with Butch and me often, hanging out with us on the hill or at the park or taking us on “serious” trips such as to the library or over to the dreaded Forsythe Clinic for dreaded dental work by dreaded (do you brush your teeth?) dental students. I do remember one thing Butch and I loved to do was to go up to the Children’s Museum, which was then in a big old house up on the Jamaicaway. There the lady would give you a pencil and a list and you could walk around for what seemed like hours checking off what you discovered. Butch has reminded me of a movie house there, and an elephant! They had 4th of July fireworks on Jamaica Pond in those days and I remember walking up there from Montebello passing people in their front yards with sparklers. You could take a rowboat out on the Pond to watch the fireworks.

Our first playground was the street. It always seemed shady and cool in the summer and we became unaffected by the steepness of the hill. The girls would play jump rope and draw with chalk on the sidewalk and pavement. We all played Hide and Seek and the boys played games like Relievio and Billy Billy Buck Buck. We always seemed to have something going with a pimple ball, such as a game played off the cement “stoops” in front of houses. If the ball rolled into a sewer it was retrieved by an elaborate operation involving a coat hanger. When you called someone out from a three-decker to play you would stand by the house and cry something like “Hyoo Jimeeey” and if you were the one inside your mother might say, “there’s that eedjit so-and-so callin’ for ye.”

In the winter when there was good snow we coasted down the street. I remember running up the hill after school to do this and gliding down by the kids still walking up. The fathers spread ashes from the coal furnaces in the houses at the bottom of the hill to keep us from going out onto Washington Street. Later we would coast and ski “up the park” across from the block at the top of Iffley Road with the Jewish kids from there. I skied with Danny Connolly up by the Bear Den nearby.

Our original gang of boys, those bedrock first and lifelong friends you “grew up with” consisted of Butch (Jack), Buddy Keegan (Charles), Tom and Charlie Cloherty (T-Bone and Punch), Jerry Morelli and me. Our numbers expanded as the years went on but that early bonding left everything among we originals as a given. We’ve remained good friends all our lives. We’ve lost the Punch since. He was our funniest, and maybe our finest.

Once a year or so Jerry’s mother Mary would have all of us kids up to their house on the top of the hill for dinner. There she would prepare a big feast, and introduce our potato-numbed palates to the wonders of Italian cuisine. I still blame Jerry and his mother as being partially responsible for the fact that I married an Italian girl. Mary was a great friend of my mother’s and they enjoyed many things such as the Lady’s Sodality at Church together.

Our gang became the “little kids”on the hill to be watched over by the ”big kids” 5-10 years older. The ones we interacted with most were Frankie O’Connor and his brother Jackie, Bobby Power, Pete Grady, and my cousins Frannie and Johnnie Tighe. They all played ball with us forever. Frankie and Bobby coached us some. I remember Frankie piling us all into his 40-something green Plymouth for a ride to the beach. Joe Tighe, who was a little older, took all the Cradocks and Tighes down to Nantasket in his first car. Bobby took me to my first movie, “Pinocchio” after asking my mother’s permission. We took the T in town to RKO Keith’s and back with his pal Bobby Teehan. Frankie once drove my father to the City Hospital to take me home after a bike riding accident in the park.

The big kids were a large part of our lives growing up. Some, like Bobby, Frankie and Frannie were more like big brothers. And Johnnie Tighe took this seriously, sometimes directing my activities out playing to keep me out of trouble. He was sort of my bodyguard (I think Helen was a few times too). He encouraged me in sports and think I suggested that he play football at J.P. High. When he left for the Army as I was entering high school it was a loss.

In later years we would have tag rush football games up the park and softball games at Cornwall playground between the big kids and the little kids, which I believe we remained to be well into our twenties. As we got older we became “the boys” on the corner but I think to many we are still “the little kids.”

Our life was rich, and most of our activities seemed to revolve around the church, Our Lady of Lourdes, as our base. Our folks brought their deep and unwavering faith from the old country and embraced the Church in America. My father was a Knight, Holy Name member and usher at Sunday Mass. Mom was active in the Lady’s Sodality and Third Order of Mary. In addition to Mary Morelli she talked often of her friends in both, including Mrs. Jordan, Mrs. Stanley and Peggy Sullivan’s mother from Lourdes Ave. She used to get a kick out of Father Downey’s “mystery rides” when he would lead the ladies on Sunday outings to an “unannounced location.” As an altar boy I served at Sunday night meetings of the Holy Name Society in church and I have never since seen a full group of men sing with such gusto and heart as those members did with “O Holy Name….”

We went to grammar school there and were taught by the good Sisters of Saint Joseph. The nuns were very dedicated and worked hard to give us a good education and make something of us. I had the honor of being president of my 8th grade class (my nephew Jackie Power achieved that distinction years later). With that came the privilege of taking the T in town during school hours to fetch the sisters’ prescriptions at Cheney’s drugstore in the old Scollay Square. That was an interesting place. Big and old-fashioned, it had exotic things such as roots and Spanish flies exhibited in big jars on shelves high on the walls. Back at school I remember during recess outside sometimes smelling the hops and barley from the Haffenreffer brewery, where Uncle Jack (Dooley) worked. We served as altar boys (or in the choir if you flunked the Latin) and played CYO baseball and basketball at Carolina Field and the Mary E. Curley School.

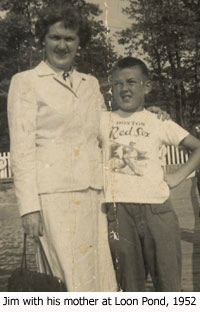

The church had a great Boy Scout troop, #21, with Frank Ledwith, a wonderful guy, as Scoutmaster. We camped at Hale Reservation in Westwood where we had a cabin and went to summer camp at Loon Pond in Lakeville, near Middleboro. There I learned how to swim, row a boat and navigate a canoe. My first year at camp I was flat afraid of the water, and started in the “non-swimmers” section at the pond. You had to pass a swimming test, probably the length of the dock, to become a “beginner” and swim in deeper water. After awhile I thought I could pass the test but was afraid of it. Every day when I got back to our campsite from swimming Danny Clifford, an assistant scoutmaster and from our corner, would check me. “Did you take the test today?” Finally, with Danny’s nudging I took it and passed, and later graduated to “swimmer” (the deepest section). Swimming became a lifelong favorite pastime for me. Thanks, Danny. The troop had a drum and bugle corps, directed by Frank’s brother Paul and a man named Gabe from East Boston. We traveled often to competitions and parades. We marched in the St. Patrick’s Day parade, in South Boston, and in New York! (Go Sox!) The troop was very popular and there were usually over 100 of us at our weekly meetings at the Teddy Roosevelt school up by Egleston Square. I remember when Frank married a very nice lady from the Hufnagle family down by the church. They had a florist shop up on Centre Street. Frank later became a school principal.

My first year at camp I was flat afraid of the water, and started in the “non-swimmers” section at the pond. You had to pass a swimming test, probably the length of the dock, to become a “beginner” and swim in deeper water. After awhile I thought I could pass the test but was afraid of it. Every day when I got back to our campsite from swimming Danny Clifford, an assistant scoutmaster and from our corner, would check me. “Did you take the test today?” Finally, with Danny’s nudging I took it and passed, and later graduated to “swimmer” (the deepest section). Swimming became a lifelong favorite pastime for me. Thanks, Danny. The troop had a drum and bugle corps, directed by Frank’s brother Paul and a man named Gabe from East Boston. We traveled often to competitions and parades. We marched in the St. Patrick’s Day parade, in South Boston, and in New York! (Go Sox!) The troop was very popular and there were usually over 100 of us at our weekly meetings at the Teddy Roosevelt school up by Egleston Square. I remember when Frank married a very nice lady from the Hufnagle family down by the church. They had a florist shop up on Centre Street. Frank later became a school principal.

The church was a lively, vibrant place in those days. I can remember standing on the corner and watching people literally pouring down Montebello and Forest Hills Street on their way to Sunday Mass. The church would fill up and Mikey Walsh would have the Sunday papers stacked on the front steps to get after. We had many occasions for celebration there, such as First Communion, Confirmation and the May Procession. The holidays especially remain in my mind. I remember walking down an icy hill on a snowy night, helping my mother and Aunt Sadie across Washington Street headed for Midnight Mass on Christmas Eve at the Old Church.

There were some other diversions for us as kids in J.P. We could walk up to Curtis Hall, by the Monument, and swim in its indoor pool called “the tank.” The library Butch and I went to with Chris was around the corner from Curtis Hall. Later we walked to a new library on Seaver Street by St. Mary of the Angels. We could go to the Neighborhood House on Lamartine Street to play basketball or take woodworking classes with Mr. Flaherty there. There was also a woodworking class in a one-room schoolhouse up on Eliot Street which the kids from Lourdes were invited to and which we enjoyed very much.

The local movie, the Egleston (“Egg box” or “Eggie”) was on Washington in the Square, which bordered on Roxbury. It was a great escape on Saturday afternoons, Westerns and Cartoons. The theatre would explode with the excitement of city-bound kids standing, jumping and some “scaling” popcorn boxes as they found themselves rushing across the wide open plains on horseback with the likes of Tom Mix or Lash Larue. Uncle Jack took me to see “The Boy With Green Hair” there. One evening as we left the Eggie Chris and I (and probably Butch) heard sirens which we found out later signaled the end of the Korean War. Sometime before that we went up on the enclosed pedestrian overpass, which ran above the Square to the T station and watched General Douglas Mac Arthur pass beneath us in a motorcade, wearing his weatherworn army cap. This was soon after President Truman had fired him.

On the same side of the street as the theatre there was a block in the square with a drugstore on either end on the corners. In the middle of the block was Azian’s 5 and 10, at which all of our sisters worked at different times. Directly across the street was The First National supermarket. Across from the theatre was the A&P. Friday nights were busy in those stores, as people would shop for their “order” of food for the week. Most of the shopping was done “by foot” and kids would line their carts up outside each store to earn money pulling orders to peoples’ homes (I think 25 or 50 cents for an order).

We had our own Radio Flyer so Butch or myself would go up with the cart on Friday night to meet Dad at the First National. Then we would cart our order home, pulling with dad’s hand on the shoulder.

One time Patsy caught the chore of walking home with me. With six kids, Mom Dad and Uncle Jack at home our order was big at least to me at 10 or 11. As I struggled to get up the hill pulling the cart I felt like my face was two inches from the pavement, while Patsy gave me pep talks all the way up about how I could read my new funny books when we got home. She found it all quite hysterical.

There was another time not so funny, when Dad and I were going down the walk alongside 81 headed for the back stairs with the order and Dad, who was upset, mentioned to me that Mary and her husband Beaver Power had been in a bad automobile accident in Nevada while driving cross-country to his Navy Duty in California. I think Beaver injured his shoulder but was o.k. after a while. Mary injured her back pretty seriously and took some time to recover. Pat, now their oldest daughter, was with them as a baby and miraculously escaped any injury.

The church remained our base, with the surrounds of J.P. our larger territory or neighborhood. But if that was the case then Franklin Park was our back yard. The park began for us at the top of the hill at Walnut where there was a wooded “island” surrounded by roadways with a path running through its middle to the other side directly across the road from the main entrance to White Stadium. This we called the “Entrance.” My earliest memories of the Park are crawling around in the tall grass where the stadium now stands. Mary tells me Mom and Aunt Sadie brought all of the Cradock and Tighe kids up to that spot often because they enjoyed it there so much. They would teach the girls how to braid and weave the grass like they did in the old country.

Then there were the Victory Gardens, created during the War, which covered the large field where the baseball diamonds are now located behind the stadium. I would go up there on summer evenings with my father, and sometimes Mr. Conlon from across the street. I remember crawling around among what were exotic to me colors and smells of the various vegetables and other plants while Dad worked and weeded. I loved it there and have kept my enjoyment of growing things since. I still have a distinct memory of being up the park with Chris and looking across a field near the Lion House, at prisoners in a stockade! They turned out to be POWs, Italians! Maybe that’s why they smiled at us. We went home and told Mom and she told us never again to go near those charmers.

As we grew the park became our playground. Our winter sports, including tobogganing and ice-skating, expanded up to the Golf Course. We skated where it was flooded for that around the old 16th hole. There was a toboggan chute on Schoolmaster’s Hill near the Ralph Waldo Emerson House.

Buddy taught me to ride a bike outside the main gate to the stadium. The idea was to start out across the street and up the hill a bit towards a rock formation we called the Giant’s Chair. (I think Joan Power fell off that Giant’s Chair once and broke her arm.) There I would get on the bike and roll down, aiming for the bushes to the left of the gate. I either “rode” the bike or crashed into the bushes. There was a method to his madness. After a few crashes (and “flights”) I got the idea, and balance. It worked!

We explored the woods at the other side of the entrance from the gate, first running along Walnut Ave. and then continuing parallel to Sigourney and then Forest Hills streets to the Brook, near where the Shattuck Hospital now stands. We named them the first, second and third woods, divided by us where they were interrupted by roadways. We saw many well-preserved gravel roads bordered by stone walls running through the woods and blocked off from the outside by large stones. Perhaps they were evidence of parkland enjoyed by earlier generations before the woods grew in. We were ever in pursuit of wildlife, however I recall only several “possible” sightings of pheasants. Our closest encounter was when a chipmunk bit Tommy. We picked blueberries in the first woods once, and Howie Russel’s mother baked us pies.

We first played ball at the park. For football we wore plastic helmets which were molded by a machine which made them more square than round. So we often appeared to be looking off askance. We played a game of mayhem called “fumbles” in which someone would take the ball and try to avoid being tackled by everybody, then to fumble intentionally or not. Then someone else would have to pick up the ball, take his punishment, and so on. I remember lying in the ripe fall grass with my head or backside or something else hurting so much that I thought I’d never get up again. Then a few minutes later up and at ‘em. We played by the stadium. We enjoyed watching many high school games there, especially when the stadium first opened and they had those dazzling Friday Night Jamborees.

We started playing baseball in a place we called “the gully” across from a drinking fountain by the stadium and down from a bench. There was a rock there shaped something like a small home plate and we kind of wore the grass down at the bases. We were so small when we started there that some of the big kids would come up and pitch to us underhanded. Larry Conlon did this and so did Frankie O’Connor (Frankie got his hits). I remember Jerry being there, just having moved up from Rossmore Road and using his uncle Chico’s glove. He was 8. And John Cloherty catching balls in the outfield.

Later we would graduate to the diamonds. We biked up there on a paved path, which started at the fountain. As we rode up leaving the stadium on the left we would pass a raised gravel roadway built up to around 10 feet by a wall of granite, and surrounding the ruins of a police department storage facility. This was called “the overlook”. My cousin Gerard Burke, who is quite a J.P. historian and who helped me with this paper, informs me that the overlook was sort of a spa in olden times from which you could view the surrounding fields, then called “the playstead,” a name given by Olmsted.

Our diamond was the one just beyond the practice field in the stadium. There we played many pickup games. When the Jamaica Plain Little League was founded we joined. Our first season was at the far diamond over by the Refectory’s “Hut” and gateway into the main park and Zoo.

Frankie has told me he umpired the league’s first game with a fellow from Forest Hills named Charlie Hoar. The game took place most likely in 1953, between the teams sponsored by the Parkview Club and the Forest Hills Merchants. Frankie was a member of Parkview, Charlie a Merchant. I was on that Parkview team, which was coached by a very nice guy from Iffley Road named Bernie Doherty,who taught me about sportsmanship,and who was well known at the Franklin Park Golf Course and as a boxing coach for J.P. youth.

Some of my fondest memories are of shagging flies with some of the big kids after pickup games at the diamonds on warm summer nights under an iridescent sky, walking home easily through the sweet-smelling park twilight to the sound of the cicadas and then down to the hill to the house at 81 where we could hear the “click-click…..clack-clack” of the elevated train, which seemed to have its own summer rhythm.

I always think of Sunday as a day of celebration. Starting with Mass the family would be free for the day, and anticipated a big dinner in the afternoon, often roast beef. Dad worked six days a week at his job as a bartender in Brighton and took full enjoyment in his day off. Sometimes we would take outings up to the park, the Rose Garden or the Zoo. I remember an annual trip on the “Nantasket Boat” from Rowe’s Wharf down to Nantasket Beach, and walking to the Feis (Irish Festival)) over at TechField in Brookline. On the way there was a small pond across the street from Jamaica Pond called Ward’s or the frog pond, which became a favorite fishing hole of Butch and mine with Dad. The holidays were the ultimate celebration. At Thanksgiving the sideboard was so laden with exotic nuts and fruit that if it didn’t groan it should have. Butch and I would have a contest at dinner to see who could fit the most food on his plate. Mom’s potato stuffing was a favorite. She used to have me taste it the night before as she was mixing it.

The holidays were the ultimate celebration. At Thanksgiving the sideboard was so laden with exotic nuts and fruit that if it didn’t groan it should have. Butch and I would have a contest at dinner to see who could fit the most food on his plate. Mom’s potato stuffing was a favorite. She used to have me taste it the night before as she was mixing it.

Dad and Mom would go all out at Christmas. I remember Chris showing us how to leave tomato soup on the mantelpiece for Santa. My godfather John Burke would come by with Uncle Jack and leave me a nice gift. Dad would always get a huge tree and on Christmas morning our living room floor was always covered with gifts.

Dad had a chore for me in the winter. He wanted to warm the house up in the evening but got home a little too late for that so in the afternoon I would go down to our bin in the cellar and “shake the ashes down” in the furnace and put a shovelful of coal in. One Christmas Eve Dad took over on the furnace and in his enthusiasm wasn’t so frugal. It was so warm in the house that we all had jolly red cheeks and slept very well.

On Sundays throughout the year the folks would often have Aunt Sadie and Uncle Pat and our Uncle Jack for dinner. Sometimes some of their old Galway friends would come over, such as Bill and Molly Tonry, Binah and Martin Crowe, and Red and Kitty Thornton. There was music in our house. Mom played the melodian, and when she was ironing she would kind of whisper-whistle old Irish tunes. On those Sundays she and Aunt Sadie would sometimes sing sweetly together, tunes like “The Galway Shawl” and the old “Galway Bay,” And I remember Tonry leaning against the built-in China cabinet as he sang “The Queen of Connamaragh.” They would visit and celebrate into the early evening. Mom and Dad always loved having company.

This then was our neighborhood, and our world until the mid-50’s when we spread our wings and graduated to high schools around the city. It was American of course but very Irish at the same time. To me it was in some ways a little like an Irish village, American-style. I don’t profess to it having been perfect. There were the natural ups and downs of life. But we never felt we wanted for anything. There are so many memories of being given so much and we all thought it a great place to grow up. I still enjoy telling people that I’m from Jamaica Plain, born (at the Faulkner) and raised in J.P.

This article continues with a large photo gallery. Click this link to see more.

Jim Cradock

December, 2007

Hamlin Garland, One of the Great Literary Pioneers of America

Boston has always been a city that prides itself on its social reform ideals, and Jamaica Plain has played its part as well. But few would think that Jamaica Plain played any part in the militant reform movement in the Midwest one hundred years ago. Yet America's leading writer of the farming frontier, Hamlin Garland, wrote his very first stories from an attic room in Jamaica Plain.

Boston has always been a city that prides itself on its social reform ideals, and Jamaica Plain has played its part as well. But few would think that Jamaica Plain played any part in the militant reform movement in the Midwest one hundred years ago. Yet America's leading writer of the farming frontier, Hamlin Garland, wrote his very first stories from an attic room in Jamaica Plain.Hamlin Garland was one of the great literary pioneers of America. The subjects of his best writing were the dirt farmers of the "middle border", that area between the land of the hunter and the land of established agriculture. In Garland's time, this was Wisconsin, Iowa and the Dakota Territory where he had grown up between 1860 and 1884.

Life was hard for his farming family, and he wanted to improve his future by becoming a teacher. A Maine minister passing through Ordway, Dakota convinced young Hamlin Garland that Boston offered more opportunities for study than did the Midwest, and Garland came to Boston in November of 1884.

After unsuccessfully trying to get into Boston University using the minister's recommendation, Garland began a period of self-instruction at the old Boston Public Library on Boylston Street, while staying in a cold, bleak room around the corner in Boylston Place. He lived in virtual poverty, slowly wasting away. In order to save the little money he brought with him, he daily spent only eight cents for breakfast, fifteen cents for dinner and ten cents on supper.

The next spring, he met the Maine minister at his home in Portland and received a recommendation to visit Dr. Hiram Cross in Jamaica Plain. The doctor had purchased some land in Dakota territory and the minister thought that Cross and Garland could talk about the West; the minister also hoped the good doctor would offer Garland advice about his frightfully run-down condition. And so Hamlin Garland took the horsehair "along winding lanes under great overarching elm trees, past apple orchards in bursting bloom... The effect upon me was somewhat like that which would be produced in the mind of a convict who should suddenly find his prison doors opening into a June meadow." The two men liked and trusted each other and Dr. Cross offered Garland a room with board for the summer at five dollars a week. Thus was Hamlin Garland installed in Dr. Cross' attic room at 21 Seaverns Avenue in Jamaica Plain.

During this time, Garland was studying and going to lectures regularly. After one talk, the speaker, Professor Moses Brown, owner of the Boston School of Oratory, asked him to give a summer course on literature. He happily accepted. The fortunate combination of a pleasant place to live and someone's confidence in his literary and speaking abilities inspired Hamlin Garland to begin to write.

His first major piece was prompted by the sound of the coal shovel beneath his window in Jamaica Plain. He said it reminded him of the sound of the corn-shucking shovel, and "The Huskin'" was accepted by American Magazine of Brooklyn, New York. The story's focus on life in the Midwest would mark Garland's entire career. For while the city made him articulate, Hamlin Garland wrote about the land he knew best.

His stories are remarkable for the realism they depicted. Garland contrasted the natural beauty of the land and the heroism of its families with the failures of the pioneer enterprise. He showed the life of a farmer in this stark region in America as unremitting labor amidst poverty and filth. Drudgery and hopelessness came with the unpredictable weather and the predictably mean spirit of the moneylender. His writings exploded the myths of the rural movement westward.

Garland saw his writing as the first wave of a true American literature, free from European convention. He believed that the local settings and realistic language of the Midwest was the basis of a future natural American literature. He also wrote extensively in support of Impressionist painting as the realistic art of the future. The writer insisted on using his stories to convey his ideas in social reform. Garland was a fervent believer in the Single Tax philosophy of Henry George, and campaigned personally for the People's Party of Iowa and the Populist Party in 1892.

The magazine stories he wrote at Seaverns Avenue were collected into his first book, Main-Traveled Roads, which is acknowledged by critics to be his best. Garland's reputation began to grow in Boston and spread throughout the country. He became friends with William Dean Howells, the Boston urban realist writer, as well as John Enneking, the impressionist painter from Hyde Park. The other writers in "honest" literature with whom he became friendly included Mark Twain, Walt Whitman and Rudyard Kipling, as well as Edward Eggleston, Joseph Kirkland and E.W. Howe.

By December 1890, he moved to 12 Moreland Street in Roxbury, and then established his home in Chicago during 1893, in order to be close to the new trends developing at the World's Fair. He married Zulime Taft, sister of the Chicago sculptor Loredo Taft, in 1899. His writings continued to be realistic and socially concerned. Then in 1919 he wrote his autobiography, A Son of the Middle Border, and its sequel, A Daughter of the Middle Border, which won a Pulitzer Prize in 1921. These books capped his career with a return to his roots and are considered among the best American biographies ever written.

He moved to California with his daughters in 1929, and died on March 4, 1940 at the age of seventy-nine. A reformer who was at the start of the populist movement, a writer of a new American literature, Hamlin Garland's reputation traveled far from its beginning in Jamaica Plain.

Sources: Hamlin Garland, A Son of the Middle Border, New York, 1917; Jean Holloway, Hamlin Garland, A Biography, Austin, 1960; Current Biography 1940; Boston City Directories, 1884-1893. Photograph courtesy of Miami University and The Hamlin Garland Society.

Copyright © 1995 Michael Reiskind

Hamlin Garland, Pulitzer Prize Winner and Noted Western Author

As a senior at Notre Dame (Indiana) I enrolled in a course entitled “Literature of the American West,” a rare curricular offering at any college then and now. Among the books on the class syllabus were Willa Cather’s O Pioneers and Hamlin Garland’s Main-Travelled Roads.

After graduation I stayed on in the Midwest and taught American literature at a high school in Cincinnati. Here I assigned novels like Cather’s My Antonia and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. I noted the connections and contrasts between “the East” and “the West” in both books.

When I returned to Boston in the early 1970s I settled in Jamaica Plain and continued to read fiction, especially by American and Canadian writers. Years later – at a reading at Harvard Book Store in Cambridge – I learned about an annual celebration of the life and fiction of Willa Cather in her hometown, Red Cloud, Nebraska. I signed up for and attended the 2014 conference sponsored by the Willa Cather Foundation.

The keynote speaker at the Cather Conference, Lee Jenkinson, focused on Cather, of course, but as an aside near the end of his address mentioned a number of other now little-read “Western” writers, including Mari Sandoz (Old Jules), E.W. Howe (The Story of a Country Town) and Hamlin Garland.

His remarks caused me to pick up my old Signet Classic paperback edition of Main-Travelled Roads. In the preface Garland writes of his coming as a young man to Boston in 1884 after years of hardscrabble farming in Wisconsin, Iowa, and the Dakota Territory. Boston was the shining city on a hill for ambitious prospective writers like Garland.

At first Garland settled in a small rooming house on Boylston Place near the old Boston Public Library. Then a friend in Boston suggested that Garland meet Dr. Hiram Cross, a Boston physician with an interest in the West due to his recent purchase of a farm in the Dakota Territory. Garland decided to “risk a dime and make the trip to Jamaica Plains, to call upon Dr. Cross.” His half-hour trip aboard a little horse-car introduced Garland to a greener Boston with its “winding lanes under great overarching elm trees, past apple-orchards in bursting bloom.”

Dr. Cross lived in a “small frame house” at 21 Seaverns Avenue in Jamaica Plain, a home “in the midst of a clump of pear trees.” Soon afterwards – in late spring 1887 – Dr. Cross invited Garland to live in the attic of his home. Garland – hard-pressed financially and loving the country atmosphere of Seaverns Avenue and Jamaica Plain – was delighted to move to a more rural setting.

From fall 1887 to spring 1888 Garland wrote a series of what he called “sketches,” that became the short stories of Main-Travelled Roads, the book that established his reputation as a writer. Garland wrote that the book’s “composition was carried on in the south attic room of Doctor Cross’s house at 21 Seaverns Avenue, Jamaica Plain.”

William Dean Howells, a prominent novelist and literary figure of the time, hailed Garland as an important new voice in American literature. The aged Walt Whitman praised Garland as one of the literary pioneers of the West. In late September 2016 I journeyed to St. Paul, Minnesota, for a family wedding. The day after the wedding I joined a small group for a walking tour of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s St. Paul. From St. Paul I headed south – first to Northfield, Minnesota, where I toured St. Olaf and Carleton Colleges – and then travelled on to my second literary destination: the hometown of Hamlin Garland, West Salem, Wisconsin.

I learned to my dismay that the Hamlin Garland Homestead had closed for the season. West Salem is tiny with a two-block downtown. I noticed one store that seemed to represent an Easterner’s idea of Wisconsin – Le Coulee Cheese Castle – and walked in and met Nick Miller, the proprietor, who personified Midwestern graciousness. When he learned that I was a Bostonian wanting to see Garland’s home he picked up his phone and dialed the President of the West Salem Historical Society, 90-year old Errol Kindschy.

Errol lives in a grand Colonial house overlooking the downtown. His house doubles as an antique shop and used bookstore. Now hobbled, he lives on the second floor and uses the stairs once a day on orders of his physician. But hearing that a Garland reader from Boston was in town he came down the stairs a second time that day to greet and chat with me. I learned quickly that Errol is an expert on the life and works of Hamlin Garland and a raconteur of the first rank. He recounted stories for an hour about Garland, sold me a couple of Garland first editions from his book stacks, and made a phone call to arrange for the Garland Homestead to be opened for me! That is the beauty of small-town America. As I was departing, Errol asked me to join the West Salem Historical Society. I did so!

I walked over to the Garland Homestead, a two-story house on the National Register of Historic Places. There Norma Schmig, another member of the West Salem Historical Society, met me and provided a well-informed hour’s talk about the home and grounds. Hamlin had purchased the “two-story frame cottage” in the early 1890s for a retirement home for his pioneer parents. For both generations it was a return to Lacrosse County and the town of West Salem, where the best years of the Garland family had been spent.

I doubled back to Le Coulee Cheese Castle, thanked Nick, and bought a $1 ice cream cone and my first-ever bag of cheese curds. I drove by two other historical homes managed by the West Salem Historical Society, and then proceeded to Neshonoc Cemetery, where Hamlin and his wife Zulime (Taft) Garland are buried – a beautiful spot on a hill on the outskirts of town.

In late fall I sent Errol Kindschy a photo of 21 Seaverns Street, the site where Garland composed his first and best-known book. Later on in his career Garland wrote family memoirs, A Son of the Middle Border and A Daughter of the Middle Border (winner of the Pulitzer prize in 1922), that traced his parents’ lives as pioneers and his own life as a best-selling author, husband, and father of two daughters.

Footnotes

1. Garland, Hamlin. A Son of the Middle Border, Grosset &Dunlap, 1917. Quotes in the sixth and seventh paragraphs: pp. 337-338. Quote in the twelfth paragraph: p. 461.

2. Garland, Hamlin. Main-Travelled Roads, New American Library of World Literature, Inc., 1962. Quotes in the eighth paragraph: p. X.

Editorial assistance provided by Kathy Griffin.

Harriet Whitcomb: A Grande Dame and Raconteur

By Walter Marx

Anyone interested in our local history soon comes upon Harriet Manning Whitcomb’s Annals and Reminiscences of Jamaica Plain, published in 61 pages at Cambridge in 1897. Its original form was a lecture given to the Tuesday Club in its clubhouse, the Loring-Greenough House at the monument. With the help of a photograph of Mrs. Whitcomb in the Bicentennial Room of the Jamaica Plain Branch Library and a letter in its files this erudite Yankee lady, looking much like Queen Victoria in her Widow of Windsor phase, can be seen more clearly.

Anyone interested in our local history soon comes upon Harriet Manning Whitcomb’s Annals and Reminiscences of Jamaica Plain, published in 61 pages at Cambridge in 1897. Its original form was a lecture given to the Tuesday Club in its clubhouse, the Loring-Greenough House at the monument. With the help of a photograph of Mrs. Whitcomb in the Bicentennial Room of the Jamaica Plain Branch Library and a letter in its files this erudite Yankee lady, looking much like Queen Victoria in her Widow of Windsor phase, can be seen more clearly.

Born Harriet Avis Manning on Joy St. on Beacon Hill in 1839, she was descended from the old Jamaica Plain May family, whose name graced this column last April in conjunction with the cleanup of the First Church Burial Ground by the Monument. The family soon moved back to the rural environs of its ancestry, and Whitcomb lived here in Jamaica Plain for 90 years. She was the first known person to be baptized in Jamaica Pond by the Rev. Dr. H. Lincoln of the First Baptist Church at Centre and Myrtle Sts. and was a member there for many years.

She later married Austin Fuller Whitcomb of Vermont, and the couple lived in a lovely house on Faulkner (or Green) Hill, lending their name to the street there when it was laid down in the early part of this century. Upon her death in 1941 at the age of 102 from pneumonia the house went to the Faulkner Hospital, which demolished it to erect an extension to their nearby Nurses’ Home which later yielded to Center House. Two magnificent trees on the corner yet remain from the Whitcomb era on the property still marked by its stone wall. The Whitcombs had three daughters, one of whom lived with her mother, widowed in 1892.

Being well situated, Mrs. Whitcomb was able and very willing to give herself to local affairs. She was a charter member of the Tuesday Club in 1892, and, having been on the Boston scene all her life and one of the oldest residents of the City at her death, was well prepared to share her memories and opinions in interviews or booklets.

She recalled meeting the famed singer, Jenny Lind, also known as “the Swedish Nightingale,” and shaking hands with the famed pre-Civil War Massachusetts senator, the legendary Daniel Webster, a friend of her father. She well remembered the Great Boston Fire of 1872.

Her pictorial association with the Widow of Windsor is very fitting, for when Mrs. Whitcomb received news of the death of her brother Charles on the day he was to have returned from Civil War action she suffered a stroke that left her lame for life.

Her house is still remembered as preserving the aura of the Civil War period for 80 years in tribute to the lost brother. Like that of her neighbor, Francis Parkman, the house abounded in flowers from a garden designed at the time of the war and never varied after that.

In a letter to the old Boston Transcript after Mrs. Whitcomb’s death, the writer noted her ever-alert mind, her indomitable religious faith, her readiness to help others, and her ability to have rapport with people of all ages. Once asked while overlooking the Arboretum if summer was the best season, Mrs. Whitcomb immediately answered, “I find beauties in all the changing seasons.” The writer felt her to be a truly remarkable personality and a model of perfection.

Photograph courtesy of Barb Vellturo, The Town of Stockbridge, Vermont

Henry Keaveney: Jamaica Plain Newspaperman

Henry Keaveney wasn’t thrilled when he failed woodshop in high school, but he’s not complaining. For one thing, he flunked that class 75 years ago. For another, his life is rich and full, in a round-about way because of that class. Keaveney, now 88 years old, sits at his dining room table in JP, his long hands resting on a red placemat. Taffy, Keaveney’s calico kitten, jumps on the table and purrs insistently, looking for company. Keaveney lets her stay.

Like many people his age, Keaveney wears a hearing aide. He has to struggle to hear people speak above background noise. These days he sometimes chooses not to attend meetings in JP because it can be difficult to pick out voices.

His memory, on the other hand, is something of a wonder. Keaveney is a rich repository of old-time JP history. He knows who served penny ice cream cones in the 1920s, and how train cars loaded with milk bottles sounded as they rattled out of the H.P. Hood plant.

He remembers the stink of the pig sty at Allandale Farm, and the flying sparks at Craffey’s blacksmith shop. He can tell you about local boys who swam in a brook next to the old Continental Dye House on Brookside Avenue. They came out dripping wet, their skin dyed blue, pink or green.

Keaveney was born on Ballard Street, just a quarter of a mile from his present home on Aldworth Street. He was an only child. “I was spoiled,” he says readily. “I didn’t have to fight for anything. Every time I yelled or cried I got what I wanted.”

Keaveney’s father worked for 25 years at the Allandale Farm greenhouse, earning $1.50 a day. Every two weeks he had a day off. Keaveney’s own lifelong career began when he flunked that famous class at Mechanical Arts High School, now called Boston Tech. It led him to quit school, but it may have been a blessing in disguise. Keaveney took a job as an errand boy at a print shop on McBride Street. Six months later he began travelling from shop to shop, learning all he could. In a short time he had experience in more than 20 Boston printing shops.

He was a prize, and the Boston Globe snapped him up. Keaveney worked in their composing room for 41 years. He was a “hand man,” designing advertisements, arranging layouts and marking up sizes. For eight of those years he worked the night shift. Keaveney remembers leaving work between 2 and 4 a.m. and waiting for the “owl car” out of Scollay Square. If he missed the trolley, Keaveney says, he walked the five miles back to Jamaica Plain in the dark.

At one time the Globe needed 400 people and a huge composing room to produce a newspaper, Keaveney says. The linotype revolutionized the newspapering business. “Hot metal,” he states. “You could produce the paper twice as fast, and with fewer people.” Now computers have revolutionized newspapers a second time. “You can put twice the paper out with half the help. If I still worked at the Globe, my job would be completely different.” Keaveney did learn once to type with both hands on a keyboard, but now he is back to picking at keys with one hand again when he types letters. He has never used a computer.

Keaveney has only good things to say about the Globe-owning Taylor family and his fellow typographical union workers. He is still a staunch union man. While telling stories about his life, he refers frequently to union activities and influences. Keaveney retired 23 years ago, just three weeks before his 65th birthday. He slowed down a tad, but his mind kept humming. Among other post-Globe jobs, he worked in the Harvard University library system, where he says he “got a lot of reading done.” Keaveney became the first president of the Jamaica Plain Historical Society. He was also a founder and first president of the defunct Jamaica Plain Senior Council.

He still has a seat on the Ward 19 Democratic Committee, and is a corporator at Faulkner Hospital. He also sits on the board of Southwest Senior Services. Keaveney keeps a small datebook with an American eagle embossed on the cover in his coat pocket, so he can keep track of meetings. These days, Keaveney says books and reading are what really make him tick. His study at home is lined with European biographies, books about U.S. presidents, history anthologies and short stories. There are also books about gardening and a selection of stories by Edgar Allen Poe. “I’m reading Truman right now,” he says.