A Biography of Bela Lyon Pratt

The Civil War had barely ended when, on December 11th, 1867, Sarah Victoria Whittlesey Pratt, age 36, gave birth in Norwich Connecticut to her fourth child, Bela Lyon Pratt. Sarah’s father, Oramel Whittlesey, had founded the first conservatory of music in New England, Music Vale Seminary in Salem, Connecticut. Her husband, George Pratt, a graduate of Yale University and a lawyer, was the son of the first Bela Lyon Pratt of East Weymouth, Massachusetts.

The Civil War had barely ended when, on December 11th, 1867, Sarah Victoria Whittlesey Pratt, age 36, gave birth in Norwich Connecticut to her fourth child, Bela Lyon Pratt. Sarah’s father, Oramel Whittlesey, had founded the first conservatory of music in New England, Music Vale Seminary in Salem, Connecticut. Her husband, George Pratt, a graduate of Yale University and a lawyer, was the son of the first Bela Lyon Pratt of East Weymouth, Massachusetts.

As Sarah Victoria held her infant boy, Bela Lyon Pratt, in her arms, it is doubtful she had any inkling that, by the turn of the century, he would already have carved out a strong artistic reputation for himself. However, given that she herself had been raised in an artistic atmosphere surrounded by music and art, it was likely that she might indeed encourage her child to follow such a path. By the time Bela was five years old, she had recorded on a little piece of notepaper:

One day after Bela had passed his 5th birthday our family physician chanced to be at our house. On the stand in my mother’s room stood some tiny models of a cat, dog, horse, a deer and other animals. The doctor picked them up and exclaimed: ‘Who made these?’ My mother, rather impatiently said ‘Bela pinches them out of beeswax. I can’t keep a bit of wax in my workbasket. He always plays with it.’

‘Why! Don’t you realize that child is a genius? He is a born sculptor!’ announced the physician, greatly to my mother’s astonishment.

I distinctly remember hearing her discussing the matter with my father in the evening. Thereafter, Bela was allowed to ‘play’ with beeswax to his great delight. As soon as he could use a knife, he began to carve various objects, which were much admired by his playmates. There happened to be a neighbor on the next street who heard of Bela’s talent. She had taken some lessons in modeling and sent word to Bela by one of the children saying she would give him some clay if he would come see her. He went, received the clay and at once modeled a lion’s head!

Bela Lyon Pratt was a quiet, unassuming family man. According to all reports, he was renowned for his generosity, humor and kindness. His love of music lead him to play cello, guitar and oboe much to his family’s delight. He had a wry sense of humor which often carried him through times of “blues” and anxieties over finances. Life for this busy man, who created more than 180 pieces of sculpture in less than fifty hears, circled around his home in Jamaica Plain MA, his studio, his professorship as head of the Sculpture Department at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston. He frequently lunched at Boston’s exclusive Tavern Club. He golfed, fished, played billiards and even established the N.E archery club, all this with his colleagues and wide circle of friends. His extended family often included brothers, sisters, nieces and nephews, who spent summers on North Haven Island, Maine, where, at his closest friend, Frank Weston Benson’s recommendation, he purchased property in 1903 on Bartlett’s Harbor, a short walk through the woods to Benson’s home and studio. To round out this New England Yankee’s very full life of work and play, he eventually owned a sizeable farm and several houses on and around the old family residence in Salem CT. There he enjoyed farming activities such as raising chickens and cows. He even, as a cash flow enterprise, planted pear and apple trees as well as vast crops of potatoes!

His early death on May 18th, 1917, at age 49, sealed shut the solid reputation he had built as a Beaux Arts, deeply American sculptor. He had helped form and become a vital part of the Boston School of Art, but it had to move ahead without his shining light.

Neither exotic nor scandalous, Pratt’s life cannot be characterized as “titillating” as can be said of many of his contemporaries. His death came at a time when the art scene was shifting away from European influence to a truly American School. Although his sculptures reflected little of the more “modern” cubist school, the character of his pieces was always clearly American in their demeanor.

Pratt’s wife, Helen Lugarda Pray Pratt, also a fine sculptor herself, carefully preserved quantities of photographs of his works, numerous articles referring to his work, as well as historic letters and documents. Most fortunately for us, she refrained from chucking his weekly personal hand-written letters, unselfconsciousness in their nature, which he had obligatorily written to his mother, Sarah Victoria Whittlesey Pratt over the years. Within these letters are snapshots of the Beaux Art period in Paris France and in America.. They tell of his colleagues, his family, his struggles and successes, all the while defining what is now referred to as “The Boston School of Art.” They are a veritable treasure trove of information, carved from his own hand.

It’s been a long time coming, but finally, Bela Lyon Pratt, eminent American sculptor enters the 21st century!

Take your time. Delve in. Follow the transformation of a work of sculpture from the initial idea to reality. Learn about the craft of modeling in clay. Discover history on the way. Get to know the players. And finally, connect this amazing, unpretentious man to his works, all 180 of them! And, don’t forget, there are multitudes of “unfinished” or “uncommissioned” works to consider too!!

Cynthia (Pratt) Kennedy Sam

May 18th, 2011 - 94 years to the day after my grandfather passed.

This article and photograph provided courtesy of the Bela Lyon Pratt Historical Society. Copyright 2011, Bela Lyon Pratt Historical Society, All Rights Reserved. For more information, please visit the Bela Lyon Pratt Historical Society web site at: http://www.belalyonpratt.com/

A Jamaica Plain Family's Day at the Beach in the Early 1900s

By Peter O’Brien, May 2016

The Beginning …

The Ebay dealer’s offering of “three journals about Jamaica Plains, Mass” was priced right even though the conditions he described ranged from good to fair to poor.

Here’s what arrived:

(1) 4 x 5.5 inch, red, cloth-bound daily memo book entitled “Physician’s Daily Memorandum, for 1900,” produced by M. J. Breitenbach Co., 100 Warren St., New York, NY. It was in good condition. Breitenbach manufactured Gude’s Pepto-Mangan, a mixture of iron and manganese. Pepto-Mangan was claimed to cure a seemingly endless list of ailments. In fact, every single dated page of this memo book carried an endorsement of the product by doctors and hospitals across the country, with examples of remarkable successes with the product. So, the diary, as it were, was an advertising handout, like the wall, wallet, desk and leather-bound calendars I get at a local bank every December, as I promise to one day make a deposit there.

The preliminary pages of the memo book are gone, and they may have identified the diarist who made penciled entries on several of the dated pages throughout the year.

The scattered notes record some daily weather conditions, household chores needing attention, planned visits to Burroughs Street, references to someone named “Bert,” and mention of a JP Minstrel Show. There are trips to Quissett Harbor in Falmouth via Sippewissett Road. The writer’s current ailments are described, as well as the hiring and firing of maids, and docking one girl a week’s pay of $10 for failing to give adequate notice of her departure.

There are also references to Tuesday Club cooking lectures, “driving” to unnamed places without mentioning whether the driving motive-force was horse or automobile. The sleeper train to Boston is mentioned but the departure point is not. There are many references to “Anna,” and a few to “Mrs. G.” The handwriting deteriorates near the last entries and then there are a few pages with the childish writing of “Anna,” who declares herself to be a “good girl.”

Physician’s Memorandum for 1900, Courtesy Peter O’Brien

Physician’s Memorandum for 1900, Courtesy Peter O’Brien Title Page, Courtesy Peter O’Brien

Title Page, Courtesy Peter O’Brien Typical Daily Entries, Courtesy Peter O’Brien

Typical Daily Entries, Courtesy Peter O’Brien Anna’s a Good Girl, Courtesy Peter O’Brien

Anna’s a Good Girl, Courtesy Peter O’Brien

Pepto-Mangan Cures All, Courtesy Peter O’Brien

Pepto-Mangan Cures All, Courtesy Peter O’Brien

(2) 5.5 x 8 inch school workbook, in fair condition. It is signed, in a beautiful hand, by “Etta F. Barton, 742 Centre St, Jamaica Plain, Mass.” It is labeled as a geometry workbook and is full of diagrams, formulae and solutions.

Etta Barton’s Signature, Courtesy Peter O’Brien

Etta Barton’s Signature, Courtesy Peter O’Brien

(3) 5.5 x 8 inch school workbook. It is in very poor condition with the covers just barely hanging on. The book is labeled on the inside of the front cover, in a neat hand, “Henrietta F. Barton, Room 9, Section B, Girls High School, West Newton Street, Boston.” It is a very detailed history notebook, written in both ink and pencil.

Henrietta Barton’s Signature, Courtesy Peter O’Brien

Henrietta Barton’s Signature, Courtesy Peter O’Brien

In one of the workbooks, an undated and unsigned letter from Winchester, NH, addressed to “May,” mentions “Grandma and Grandpa Goodnow,” and that the writer may be “the first automobilist to climb some of the hills” they negotiated to get to the home of Grandpa Goodnow’s only aunt, Minerva, after visiting Doane’s Falls in Royalston, MA. It also describes a side trip in a two-horse, three-seat buckboard to a farm where J.W. [Goodnow?] lived after his mother remarried.

Henrietta F. Barton

Using all the Internet resources available today, we were able to determine the following:

Henrietta (Etta) F. Barton was born on March 2, 1872 at Walnut Avenue in Jamaica Plain. Her parents were Henry W. Barton and Mary A. Sadler, both of whom were born in England. Henry was a lamplighter. In 1880, Henrietta had eight siblings ranging from ages three to twenty-two. Henrietta was the diarist who made the entries in the red memo book, as we shall see as the pieces come together.

By 1883, the Bartons were living on South Street in Jamaica Plain, opposite Keyes Street, the present McBride Street. By 1890, they were residing at 742 Centre Street between Harris Avenue and Greenough Avenue, and Henry continued working as a lamplighter.

In 1891, Henrietta graduated from Girl’s High School in Boston and two years later, in 1893, she graduated from the Boston Normal School, qualified as a “Substitute, Temporary or Permanent, Assistant Grammar Teacher.”

On June 28, 1893, Henrietta married Albert (Bert) W. Goodnow.

Albert W. Goodnow

Albert was born on March 29, 1871, in Jamaica Plain. He was the son of Joseph W. and Helen M. Goodnow. Joseph was born in Vermont in December 1843. Helen was born in New Hampshire in 1842. Joseph and Helen were married in 1869. Joseph and Helen Goodnow lived at 27 Burroughs Street in Jamaica Plain. Joseph is listed as a baker and confectioner, and later as owner of a stable at 716 Centre Street. Some sources indicate that by 1910, he may have become a real estate broker.

The Goodnow stable was destroyed by fire in January of 19171. One of the horses lost belonged to the farrier, John Mahoney. In 1925, John owned the blacksmith shop at 10 McBride Street, next to the Coffee Tree Inn. That shop had been started by Ignatius J. Craffey, about 1910, and after Mahoney, it was owned to the 1950s by James “Jimmy” Lovett.

Albert was a partner in Ranlet & Goodnow, Hay and Grain Dealers, located in the Grain Exchange Building in Boston. He lived with his wife Henrietta and daughter, Anna, at 27 Robinwood Avenue, Jamaica Plain. Their household included maids, Charlotte M. Swanson, and later, Kate Corkum, and still later, Katherine McHale. Their coachman, James Crocker, also lived with them.

Anna S. Goodnow

Albert and Henrietta’s daughter, Anna, was born in Jamaica Plain, September 16, 1894. When grown, Anna married Farnsworth Keith Baker, of Falmouth. Anna and Farnsworth had three children.

Farnsworth Keith Baker

Farnsworth K. Baker was born in Boston in 1894 and raised in Falmouth. He was the son of a Boston realtor, Edward F. Baker. He graduated from Harvard in 1917. Farnsworth was a WWII navy veteran and a history teacher at Falmouth High School. At one time he was listed as owner of properties at 90 and 112 Dudley Street, Boston. He was a musician and a charter boat captain. He and Anna lived at 189 Clinton Avenue, Falmouth.

Falmouth becomes FALMOUTH

Between 1873 and 1960 a residential area of about 126 acres, called Belvidere Plains, slowly evolved adjacent to Falmouth Inner Harbor and fronting on the ocean. The map depicts the boundaries of the site. Originally flat farmland, it sits just a few feet above sea level. The buildings are a mix of single-family, multi-family, and public housing buildings. Eighteen distinct building styles occupy the 302 residential lots.2

Map of Belvidere Plains, Courtesy Massachusetts Historical Commission

Map of Belvidere Plains, Courtesy Massachusetts Historical Commission

Albert and Henrietta Goodnow were long-time summer residents of Falmouth and in 1900 were one of only 13 families summering in Falmouth.

In October, 1887, Joseph W. Goodnow, the baker and confectioner from Jamaica Plain, bought a large tract near Deacon’s Pond which was fed by the Herring River. Joseph acquired the land from the heirs of master mariner William H. Bourne. The pond and river would later be dredged to form Falmouth inner harbor. Part of this tract was deeded to the state in 1907 by Albert Goodnow for digging the inner harbor. The spoil from the dredging was used as fill along Girard Avenue, and the house at 79 Girard sits upon that fill. Joseph sold that site to Norwood realtor Erwin A. Bigelow.

In July 1902, Bigelow sold the land, in two deeds, to Henrietta Goodnow. By 1910 the Goodnows had built a house on the western part of this tract at 63 Girard Avenue. And by that year, Joseph Goodnow was a real estate broker. Sometime before 1907, Albert Goodnow bought and sold several lots in the area.

In 1907, Henrietta sold 1.5 acres of this tract to Marion C. Robinson of Houghton, Michigan, whose husband, Dean, was an attorney. Robinson then sold the land at 79 Girard Avenue to Maxwell J. Lowry in 1917, and Lowry built the house there in 1919. Lowry, a wholesale patent leather merchant, owned a plant in Mansfield, MA which colored patent leather black. The house was modified in the 1930s and the Lowrys summered there until 1947.

It is not known if the five-bedroom, five-bath house currently at 63 Girard Avenue is the same house built by Albert and Henrietta Goodnow in 1910. It has recently been estimated at $4,225,376.00 but is not currently for sale.3

63 Girard Avenue, Falmouth, Courtesy Google Maps

63 Girard Avenue, Falmouth, Courtesy Google Maps

In 1924, Farnsworth Baker, Albert and Henrietta’s son-in-law, bought a large piece of land fronting on Clinton and Queen streets. He subdivided the parcel into 62 house lots and laid out new roads including Harborway (now Swing Lane,) Richards Road and Bourne (now Lowry) Road, Lewis (now Belvidere) Road, Hatch Road and Robinson Road. His father-in-law, Albert Goodnow, built the first house on Swing Lane at #45 in about 1924. In September 1939 Farnsworth Baker sold lot 4, upon which 45 Swing Lane stood, and adjoining lot 5 to Charles Stuart Robertson, a Taunton curtain manufacturer. Swing Lane was renamed for his wife, Elizabeth (Swing) Robertson.

Farnsworth K. Baker was involved in development of the area until about 1941 when he sold 12 lots at the northern end of Lewis (now Belvidere) Road to John F Ferreira.

The End …

And so, what was originally a summer retreat in Falmouth for the Goodnows of Jamaica Plain, became a family enterprise, developing prime oceanfront land. It involved Joseph Goodnow and his son, Albert, and daughter-in-law, Henrietta Goodnow. Albert and Henrietta’s son-in-law, Farnsworth Keith Baker, carried on the enterprise to the 1940s. By then, Farnsworth’s mother-in-law, Henrietta F. (Barton) Goodnow, was living with him at 189 Clinton Avenue in Falmouth, a long way from 742 Centre Street, Jamaica Plain.

189 Clinton Avenue, Falmouth, Courtesy Massachusetts Historical Commission

189 Clinton Avenue, Falmouth, Courtesy Massachusetts Historical Commission

And we would never have known but for an Ebay offering of “three journals about Jamaica Plains, Mass.”

References:

1. Courtesy Mark Bulger and “Remember Jamaica Plain?” [blog].

2. Massachusetts Historical Commission and Falmouth Historical Society: Inventory Form A Continuation Sheet: Falmouth, Belvidere Plains

3. Zillow.com real estate website.

Production assistance provided by Kathy Griffin.

African-American Women in Jamaica Plain History

When Mary Smoyer conducts the annual Women’s History Walk through Jamaica Plain, Maud Cuney Hare (1874-1936) will be the first African-American woman included. It seems appropriate; her life’s work is a testimony to make known the cultural achievements of the black community.

Maud C. Hare was a multi-talented genius: pianist-lecturer, composer, playwright, biographer, poetry editor, folklorist, Black music historian and collector, founder and director of The Allied Arts Centre in Boston.

Hare moved to Jamaica Plain in 1904 after her marriage to William Parker Hare. The couple resided at 43 Sheridan Street for years before her death in 1936.

The granddaughter of slaves, Hare came from a prominent family of Galveston, Texas. Her father, Norris W. Cuney, was a pioneer in black politics and a successful businessman. Her mother, Adelina Dowdy (Cuney) sang publicly on occasion.

Maud Cuney first came to Boston in 1890, after a summer spent in Newport R.I., to attend the New England Conservatory. She faced discrimination as one of only two “colored” students in the school.

Her father received a letter in late October asking him to remove Maud since many of the students suffered from “race prejudice.” Mr. Cuney wrote an eloquent letter back to the school, flatly refusing. Affectionately praising his daughter he wrote to her, “I can safely trust my good name in your hands.”

The incident outraged the Colored National League, which threatened to have the doors of the building closed. Years later Hare wrote about how she stayed and was “subjected to many petty indignities,” but “insisted on proper treatment.” She was only sixteen and far away from home. Later, her friend W.E.B. DuBois would call her “the bravest woman” he’d ever known.

Maud Cuney Hare is best known for her book: Negro Musicians and their Music (1936). Reaching back to the African homeland and diaspora, she gathered materials and collected songs in her wide travels in Mexico, the Virgin Islands, and Puerto Rico, Cuba and throughout the United States. The book included biographies of contemporary musicians, as well as early black pioneers of American and international renown.

For many years she was active as a musician-pianist-lecturer, touring with her partner of twenty years, baritone William Howard Richardson. They specialized in African-American and Creole music and their concerts received rave reviews from major newspapers.

In 1919, their concert-lecture at the Boston Public Library was the first presentation of a musician of color in the B.P.L. series. They gave concerts with many of the other leading musicians of their day and were closely associated with Roland Hayes and Clarence Cameron White.

In 1927, with no money, Hare founded the Allied Arts Centre in Boston, an ambitious project. The Centre held concerts, lectures, and classes in art, music and drama. Both known and up-and-coming writers produced original and published plays. Hare’s own “Antar of Araby”, about a fifth-century poet-warrior, was produced with music by Clarence Cameron White, Hare and Montage Ring (Ira Aldridge).

Many talented people from Boston’s black community participated: some would develop national reputations as artists in their fields. The Allied Arts productions received praise from the newspapers, and the house was usually filled with a mixed audience.

Written By Elizabeth Quinlan. Reprinted with permission from the August 28, 1992 Jamaica Plain Gazette.Copyright © Gazette Publications, Inc.

Arborway Associates

Based on a 2011 interview with Ted Walsh, a 73-year resident of Rosemary Street, one of the founders of Arborway Associates.

By Peter O’Brien, September, 2011

In the early 1950s a group of returning veterans who had grown up together as the Rosemary Rosebuds, from Rosemary and South Streets, decided to form an association to expand their social activities which until then were spontaneous outings to the movies, day-trips to the beach, and various sports events and parties. Those outings were launched from the group’s regular meeting place, “the mailbox,” located at Rosemary and South Streets.

They hoped that by adopting an area-wide name, Arborway Associates, they would encourage wider membership and they could sponsor dances, group rentals at local beaches and seaside communities, and other social gatherings that would attract others, especially young women, from near and far corners of Jamaica Plain. It was also hoped it would advance the social graces of the young veterans, especially in the mysteries of ballroom dancing, since many of the then-popular dance halls like Moseley’s in Dedham, The Totem Pole in Newton, Coral Gables in Weymouth, The Beachcomber in Wollaston and the dance halls at Nantasket, Rexhame, and Revere beaches were encouraging stag as well as couples’ attendance. Irish dances were regularly held at Hibernian Hall at Dudley Street and the nearby Metropolitan or Hibernia Hall at Forest Hills, but most dances were avoided by the dance-shy Rosebuds.

Ironically, the Arborway Associate’s first endeavor was to sponsor a dance at the Hotel Bradford, located at 275 Tremont Street, Boston. The Bradford held regular, well-attended, dances led by the well-known Boston dance bandleader, Baron Hugo. The association’s first annual dance was scheduled for April 23, 1954 and it required much planning and coordination as well as an intense sales effort to fill a small book of ads from generous sponsors and supporters. A copy of the book of ads can be found here.

Sadly, the dance was poorly attended and thus was barely able to break-even, despite the modestly successful ad-book sales. It was, however, a valuable learning experience in everything except dancing and the Rosebuds continued to avoid the dance floor until, as they got older, free flowing spirits loosened them up and provided the courage to get out there during weddings and co-ed parties.

So the Arborway Associates died after the one attempt to grow the Rosemary Rosebuds’ social lives. Soon, as marriage and family obligations took over, nearly the entire original group left Jamaica Plain, scattering the once close-knit crowd. The break of nearly 60 years was closed by a 2010 informal reunion at a Doyle’s luncheon. The luncheon group is expanding as they continue to meet to tell ‘war’ stories and to reminisce about growing up in the good old days of 1940s and 50s Jamaica Plain. To a man they agree there was no better place. And, best of all, they all eventually became very good dancers and several married Irish colleens they met at the Irish dances.

2010 Reunion at Doyle’s

2010 Reunion at Doyle’s 2010 Reunion at Doyle’s

2010 Reunion at Doyle’s

Bacon Family

In 1845, Daniel Bacon, a retired China trade captain from Barnstable, bought some of Prince's land and the next year built a mansion behind the present 156 Prince Street. Two granite posts and a sunken driveway indicate its site off the street today. Prospering as a ship owner, Bacon retained John Prince's name for the place, Spring Hill Farm, from an underground feeder of Jamaica Pond on the property. In 1851 his son William took control of the land and soon purchased the rest of the hillside from the Goddard Family of Brookline. Here we see Prince Street in January 1893. The photograph is by the Olmsted Brothers and is provided courtesy of the Frances Loeb Library, Graduate School of Design, Harvard University.

In 1845, Daniel Bacon, a retired China trade captain from Barnstable, bought some of Prince's land and the next year built a mansion behind the present 156 Prince Street. Two granite posts and a sunken driveway indicate its site off the street today. Prospering as a ship owner, Bacon retained John Prince's name for the place, Spring Hill Farm, from an underground feeder of Jamaica Pond on the property. In 1851 his son William took control of the land and soon purchased the rest of the hillside from the Goddard Family of Brookline. Here we see Prince Street in January 1893. The photograph is by the Olmsted Brothers and is provided courtesy of the Frances Loeb Library, Graduate School of Design, Harvard University.The Goddards had already sold their holdings between the Pond and Prince Street to others. Parkman bought his Pondside cottage in 1854 from the Chickerings of piano fame. In 1810, the Goddards built the still-standing farmhouse at Prince and Perkins Streets. William Bacon built his mansion just below the crest of Spring Hill (all owned by the Hellenic College since 1946), and the Hill supported four generations of the family. Most illustrious was William's son, Robert, though he was not always present on the scene.

Born there in 1860, he was in the same Harvard class as Theodore Roosevelt. He entered the investment banking business in Boston, soon attracted the notice of J. P. Morgan, and moved to New York City, becoming a junior partner and administrative head of the House of Morgan in 1899. He retired in 1903 and devoted himself to his own affairs in Boston, sitting on the boards of prominent railroads and businesses, including US Steel, Edison Electric and National City Bank. Upon being nominated Assistant Secretary of State, Bacon resigned from these posts.

He acted as assistant to Secretaries Root and Taft and became Secretary himself when Taft became President and later became his ambassador to France. Bacon's business background helped greatly in dealing with the era's industrial nations and in setting up the State Department more efficiently. He contributed much to settling troubles with Cuba, Venezuela and Panama. Life on the Hill at this time when Bacon was away is nicely seen in the Moss Hill memoir of Mary Bowditch, when she went to primary school at Spring Hill:

"I found the boys to be the most friendly playmates. They included me in all their games. I felt equal to them. Grandpa William Bacon was always in the offing at recess time with his two handsome French poodles. If we transgressed, Grandpa often flew at us, but his bark was worse than his bite. Robin Bacon was my best friend among the boys. Gaspar was younger and Eliot a darling baby in his carriage."

When the Republican hold on the Presidency ended in 1912, Robert Bacon returned to Jamaica Plain. With the outbreak of World War I he was off to France, managing the American Field Ambulance Service and as aide-de-campe to General Pershing. The war wore him out, and he died of surgical complications in a Boston hospital just short of his 60th birthday.

His second son Gaspar was ready to step on stage. Born in 1886 and Harvard-educated, he too had fought in Europe. Yet, Spring Hill was always his headquarters after legal training. Gaspar soon entered politics and served as President of the Senate (1929-32) and as Lieutenant Governor under Democratic Governor J. B. Ely. Bacon was a progressive Republican, a good speaker and unusually popular throughout the state, a sensitive intellectual, whose writings were widely read.

The 1934 election set him against "Boston's Robin Hood," J.M. Curley, his neighbor across the Pond at 350 Jamaicaway. Bacon had long stalked Curley and relished the fight. Yet, the Great Depression - blamed on all Republicans - burdened him. The sly Curley managed to link Bacon to J. P. Morgan, though it was his father's connection. Curley hated the old Boston stock, and Gaspar Griswold Bacon's very name was too good to let go. Curley and his ticket swept into office - a first in Massachusetts's history. The New Deal was in full swing.

Bacon retired from politics, took up teaching international relations at Boston University, and practiced law. Just before the start of World War II (in which he served with distinction) he sold Spring Hill to V. Barletta. He returned to Boston after the war and died on Christmas Day 1947. By that time Spring Hill's new owner had already razed Daniel Bacon's manse and was living in the William Bacon's house. After a fire in 1945 it was repaired but finally demolished in 1952, with a ranch-style on the Daniel Bacon site replacing it.

The Hill as we know it became one unit when Hellenic College (after taking over the old Weld property on the Brookline side in 1947) bought 31 acres of the Bacon estate from Barletta. This is the hillside backdrop for the Pond, undeveloped and so far protected. It is something perhaps too long taken for granted and requires cooperation among many to assure its quiet and scenic use.

By Walter H. Marx. Sources: R. Heath, "Hellenic Hill," Boston, 1990; National Encyclopedia of American Biography; M.O. Bowditch, "Moss Hill: A Memoir"; J. F. Dinneen, "The Purple Shamrock," New York, 1949, Chap. 18

Reprinted with permission from the August 27, 1993 Jamaica Plain Gazette. Copyright © Gazette Publications, Inc.

Benjamin Bussey

Benjamin Franklin Sturtevant, Inventor and Industrialist

Benjamin Franklin Sturtevant (1833-1890) was a Jamaica Plain inventor and industrialist who filed more than 60 U.S. patents. Sturtevant’s patents related to fans revolutionized manufacturing worldwide and played a special role in the advancement of the shoe making industry in 1860s New England. Sturtevant built the first commercially successful blower in 1864.

Sturtevant was born into a poor Maine farming family. He left home at age 15 to work in Northbridge, Massachusetts. He later returned to Maine and became a skilled shoemaker. He devised a crude machine used in shoe manufacturing and came to Boston in 1856 seeking backing for further development. He worked on his design from 1857 to 1859 and secured five patents for design improvements. In December 1859 he patented a special spiral veneer lathe to manufacture stock for shoe-peg machines.

Sturtevant set up a successful manufacturing plant in Conway, New Hampshire to manufacture wooden shoe pegs and from that base sold materials to factories around the world. Sturtevant was troubled by the airborne wood dust created by the machines in his factory and went to work designing a way to eliminate the dust and its resulting health effects. In 1867 he patented a rotary exhaust fan and began manufacturing the fan and selling it to industrial buyers across the country.

Image provided courtesy of the New England Wireless and Steam Museum

With the exhaust fan business doing well, Sturtevant went to work designing air blowers, fans, and pneumatic conveyors. In 1878 he built a factory near the current intersection of Green and Amory Streets in Jamaica Plain. At the time, it was the largest fan manufacturing plant in the world. At its peak, the plant produced 5,000 blowers per year and employed about 400 workers. Sturtevant opened branch outlets in New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Oregon, England, and Germany.

Sturtevant lived at 11 Revere Street until 1889 and then at 60 Elm Street. He died in his home on April 17, 1890. Sturtevant had two daughters, the younger of whom, Lilla married Eugene Noble Foss on June 12, 1884. The Foss family lived at 8 Everett Street from 1884 until 1905. Sturtevant came to know young Eugene Noble Foss while he was a successful salesman for the Vermont-based St. Albans Manufacturing Company.

Foss home at 8 Everett Street in Jamaica Plain. Photograph 2007 by Charile Rosenberg.

Sturtevant hired Foss in 1882 and put him in charge of the manufacturing department. Two years later Foss became treasurer and general manager. Upon Sturtevant’s death, he was elected president. He later directed several other manufacturing enterprises but resigned all corporate positions when he was elected to his first political office. Foss served as governor of Massachusetts from 1910 to 1913.

In addition to the industrial fan line, the Jamaica Plain factory also produced American Napier automobiles from 1904 until 1909. The Sturtevant Aeroplane Company operated from 1915-1918 in Jamaica Plain building military aircraft for both the U.S. Army and the U.S. Navy for use in World War I. Sturtevant’s son-in-law, Eugene Foss, moved the main manufacturing operations to Hyde Park in the early 1900’s and the large building complex remains there today. A photograph of the Hyde Park facility is shown here to the right. Westinghouse purchased B. F. Sturtevant Co. in 1945 and continued to operate a Sturtevant Division. The Howden Fan Company bought the Sturtevant brand in 1988 and continued to manufacture Sturtevant fans, selling them under the Howden Buffalo name. Sturtevant fans were recently installed as part of the Central Artery project to ventilate Big Dig tunnels. Howden Buffalo’s local offices are located in the old Sturtevant complex (now Westinghouse Plaza) in Hyde Park. The entire Sturtevant fan line was later sold to Acme Manufacturing Corporation, a family-owned business in Claremore, Oklahoma that continues to build fans under the original Sturtevant product names.

Sturtevant’s son-in-law, Eugene Foss, moved the main manufacturing operations to Hyde Park in the early 1900’s and the large building complex remains there today. A photograph of the Hyde Park facility is shown here to the right. Westinghouse purchased B. F. Sturtevant Co. in 1945 and continued to operate a Sturtevant Division. The Howden Fan Company bought the Sturtevant brand in 1988 and continued to manufacture Sturtevant fans, selling them under the Howden Buffalo name. Sturtevant fans were recently installed as part of the Central Artery project to ventilate Big Dig tunnels. Howden Buffalo’s local offices are located in the old Sturtevant complex (now Westinghouse Plaza) in Hyde Park. The entire Sturtevant fan line was later sold to Acme Manufacturing Corporation, a family-owned business in Claremore, Oklahoma that continues to build fans under the original Sturtevant product names.

The Sturtevant and Foss families are buried in Jamaica Plain’s Forest Hills Cemetery in nearby plots.

Photographs of the Sturtevant plant in Jamaica Plain from the 1919 Aircraft Year Book

Sources:

1919 Aircraft Year Book, Aircraft Manufacturers Association Inc.

Air Conditioning, Heating & Refrigeration News, Nov 2001, An early history of comfort heating. Bernard Nagengast.

“Benjamin Franklin Sturtevant” Dictionary of American Biography

Heating/Piping/Air Conditioning Engineering, Oct 2002, Industrial ventilation throughout the 20th Century. Kenneth E. Robinson.

J.D. Van Slyck, New England Manufacturers and Manufactories (1879)

Old Woodworking Machines web site

The New Encyclopedia of Motorcars, 1885 to the Present, GN Georgano, editor. Dutton, New York, 1982. U.S. Patent Office

By Charlie Rosenberg and Michael Reiskind

Copyright © 2003 Jamaica Plain Historical Society

Benjamin Goddard's Diary

by W. H. Marx

The Jamaica Plain Historical Society recently reprinted extracts from the 1812-54 diaries of our Brookline neighbor, Benjamin Goddard (1766-1861). He was one of the 15 children in the fourth generation of the family raised on the Goddard Farm, whose existence is commemorated by a plaque on the road that connects Jamaica Plain with West Roxbury and Newton. In keeping with the custom, when the older son was ready to take over the farm, in 1787 Benjamin’s parents retired to a house near the present Rt. 9. Benjamin e had already started off on his own with an associate with a store in Boston and then with his brother Nathaniel, a shipping merchant.

With his share from just one voyage, Benjamin was able to build his own home near his father’s in 1811 just before the War of 1812. The war brought hard times to New England, as his diaries attest. He died in 1841 at the remarkable age of 95.

The house was later moved and still stands at 43 Summer St. The extracts show a gentlemen farmer and a pleasant person, whose eulogy sermon published the Sunday after his funeral mentioned his perseverance, loyalty, strong native sense, clear judgement, justice, and integrity and terms him a wise steward and benefactor with uniform cheerfulness and affection.

When his diaries were discovered after 1900 among family papers, they were first thought to be mere farm accounts. Fortunately, their true worth was discovered when they were presented to the Brookline Historical Society. Unfortunately, they have never been fully edited and published. It is not surprising that when J. G. Curtis published his town history in 1933 he chose the following from what had been published in the Society’s Proceedings in 1911.

In this harvest season Benjamin Goddard comes across the years vividly and merits more study for his picture of our area, which yet boasts of the only working farm in Boston of the many once here.

October 24, 1817: The autumn thus far has been remarkably favorable for the ingathering of the harvest. The ground (is) very dry and springs low. Most people are forward in their work. We finished digging potatoes and have now gathered nearly all the apples. Have barrelled 100 barrels; some more gathered but for want of barrels are in heaps. Have already made barrels of cider—mostly for vinegar. Gathered the garden vegetables excepting turnips, cabbages, parsnips, and celery. All these will yet improve. Have concluded to let the corn stand a while longer, the stalk not being sufficiently dry. The quality of the corn is extraordinarily fine and the quantity more abundant than usual. On the whole the harvest is great and good.

November 8, 1817: Took in cabbages, cauliflowers, cale and celery. These finish the harvesting for this season excepting three cheeses of cider to make. The corn all husked and housed. The potatoes in the cellar sold; apples in barrels and at least half sold and delivered. So we are nearly ready for winter. Soap and apple sauce made for season. Good luck attended both except the first kettle, which was drove with so much zeal as to get a little burned at the bottom. Like other misfortune it produced good, for the next was managed with caution and produced good.

December 12, 1817: Myself taking care of home; an employment very pleasant at this season as it required but little manual labor and is fraught with many delights. The barn, granary, and cellar are stored with the productions of the farm by the labor of man and beast. The most delightful part of the whole is dealing out daily portions as their necessities shall require and at the same time seeing them fatten upon the proceeds of their own.”

This article appeared originally in the October 8, 1991 edition of the Jamaica Plain Gazette and is used with permission.

Sources:

E. W. Baker, “Extracts from Benjamin Goddard’s Diary,” Brookline Historical Society Proceedings, 1911, 16-47

J. G. Curtis, History of the Town of Brookline, Boston, 1933, 117/8

N. F. Little, Some Old Brookline House, Brookline Historical Society, 1949

Bob Duerden's Jamaica Plain

“And finally, what is your fondest memory of growing up in Jamaica Plain? Pause… My friends on Danforth and Lamartine Streets and the things we did together.”

From a March 11, 2015 interview with former resident, Robert Duerden, of Green Valley, Arizona. A career Marine and long-time Boston Gas employee, Bob Duerden’s Jamaica Plain is unique but he shares the same experience of many growing up in a very special place.

By Peter O’Brien, March, 2015

Bob’s Beginnings

Robert F. Duerden was born on February 6, 1936, at Boston City Hospital, as it was known then. It’s now called Boston Medical Center. His father, Ralph E. Duerden, came from Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, and had worked as a steward on the old Boston to Yarmouth Ferry when it was an overnight cruise. His mother, Mary (Long), grew up on Lawn Street in Roxbury; called by many who lived there, “the sunny side” of Mission Hill.

Bob’s sister, Carole (Duerden) Lee, of Millis, was also born at Boston City Hospital and was named after the beautiful movie star, Carole Lombard, whom their mother loved.

The Duerdens lived at 39 Danforth Street in a four-room, cold-water flat in a two-decker. There was neither hot water, nor central heat. An old black cast-iron kerosene stove served for heating and cooking in the kitchen, while the parlor was warmed by a small kerosene heater. Bob remembers bed-time buried under several blankets and laying perfectly still until his body warmed the sheets. In the morning, a coat of “fern” frost covered the inside of the bedroom windows. Years later, Bob’s remarkably good health was thought to be related to his hardy tolerance of the cold winter nights in Jamaica Plain.

Duerden home at 39 Danforth Street Their next-door neighbor, at 43 Danforth, was Al Wittenauer’s garage. Al was the Duerden’s landlord and a no-nonsense German whose cigar smoke still lingers in Bob’s memory.

Duerden home at 39 Danforth Street Their next-door neighbor, at 43 Danforth, was Al Wittenauer’s garage. Al was the Duerden’s landlord and a no-nonsense German whose cigar smoke still lingers in Bob’s memory.

Next to Al’s garage, at 45 Danforth, was the well-known Boylston Schul-Verein German Club. The club has since moved to Walpole, Massachusetts but the Danforth Street building is still there housing Spontaneous Celebrations, a community arts center. During WWII, the FBI closed the club a couple of times as spies were being seen everywhere and both German and Japanese Americans felt the government’s scrutiny and harassment.

Boylston Schul-Verein German Club at 45 Danforth Street Working Parents

Boylston Schul-Verein German Club at 45 Danforth Street Working Parents

Bob’s dad, Ralph Duerden, worked 39 years in the shipping department at Salada Tea in Boston. This Boston location was once the company’s U.S. headquarters. Salada’s 12-foot high bronze doors, installed in 1927 at 330 Stuart Street, are among Boston’s many attractions. Depicted on the doors is the harvesting of tea in Ceylon and shipment of it to the west.

Salada Building bronze doors: Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones collection

Salada Building bronze doors: Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones collection Salada Building bronze doors: Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones collection One of Bob’s proudest memories of his dad was when he was home on Marine Corps leave about 1955. His dad asked Bob if he would wear his uniform and accompany him to the streetcar stop opposite the A&P Store on Centre Street where for years he commuted to work. He told Bob how proud he was of him and wanted to introduce his new Marine to his fellow riders on the streetcar. Bob of course said yes and spit-shined his shoes, polished his brass insignia and pressed his new “tropicals” uniform to razor sharp creases. While still only a PFC and with only a Marksmanship badge, the Marine uniform made any young man look like a recruiting poster!

Salada Building bronze doors: Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones collection One of Bob’s proudest memories of his dad was when he was home on Marine Corps leave about 1955. His dad asked Bob if he would wear his uniform and accompany him to the streetcar stop opposite the A&P Store on Centre Street where for years he commuted to work. He told Bob how proud he was of him and wanted to introduce his new Marine to his fellow riders on the streetcar. Bob of course said yes and spit-shined his shoes, polished his brass insignia and pressed his new “tropicals” uniform to razor sharp creases. While still only a PFC and with only a Marksmanship badge, the Marine uniform made any young man look like a recruiting poster!

At 6:00 am the next morning they walked to the streetcar stop and his dad proudly introduced him to his fellow commuters. The streetcar came and Bob decided to board it with his dad who introduced him to the conductor who refused to let Bob pay the fare. (The conductor was his mother’s uncle!) At the Salada building he met many more employees including the President of the company, a Mr. Thacker. Bob was never more proud of his dad and vice versa. Bob’s father passed in 1963 and Bob has never forgotten the compassion shown to his dad by the Salada Tea Company.

Bob’s mother, Mary, had a really fun job. She worked the hot-dog stand behind home plate at Fenway Park! She loved baseball, and for years scored the games in a home-made, spiral-bound, notebook lined out for the game’s roster to record each batter’s performance in true score-keeping notation. She became an expert on the Sox and could recite many milestones, including their 1918 World Series games. She was said to know more about baseball than everyone on their street combined. Sadly, when she passed at age 93, the years’ of homemade Red Sox box-scores could not be found.

Bob remembers his mother sitting on the stoop as several Red Sox players walked by the house on the way to the German Club which was then a very popular nightspot. Joe Cronin, former Red Sox player and later Manager, stopped one day and said “hey, I know you” remembering her from Fenway’s hot-dog stand. Thereafter, he would always stop and chat with her about baseball and the Red Sox.

Joe Cronin, Boston Red Sox Education

Joe Cronin, Boston Red Sox Education

Bob attended the Chestnut Avenue School for K-2, and the Wyman School for 3rd and 4th grade, followed by the Lowell School for 7th and 8th grade, and then on to the Mary E. Curley School for 9th grade.

He then attended Boston Technical High School, formerly known as Mechanics Arts, located at Belvidere and Dalton Streets in Boston, where the present Hilton and Sheraton hotels are located. After two days under teacher/coach, William “Dutchie” Holland, Bob decided Boston Trade School would be a better fit. He went to Trade seeking a transfer and found a sympathetic assistant principal, Mr. Murphy from Mission Hill, who said he could only find room for him in the Electrical course.

Boston Trade School was one of the several Boston high schools that taught useful trades including printing, woodworking, forging (blacksmithing), pattern making, electrical work, machine shop, and automotive repair on an alternating weekly basis; i.e. a week in the shop followed by a week in the classroom.

Many a young man went on to a productive life’s work with the skills learned at Boston Trade School. In Bob’s case, the electrical training helped him immensely in his Marine aircraft maintenance job. He says his time at Boston Trade was a life-changing experience.

Bob graduated in 1953 and remembers his “one-button-roll” suit bought for the event at the fine Callahan’s men’s clothing store at 362c Centre Street, at the corner of Forbes Street.

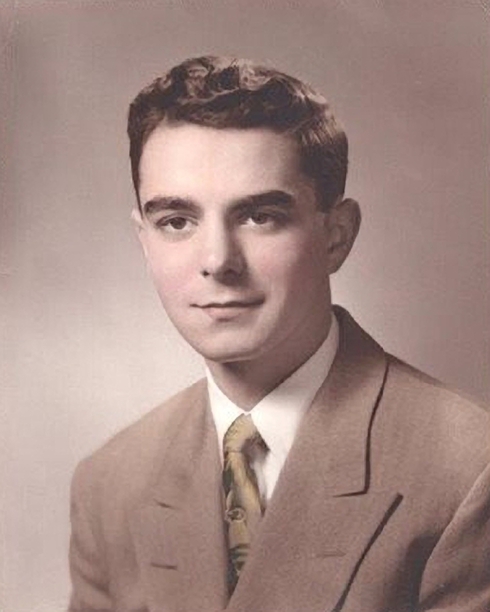

1953 Portrait of Bob Duerden at Boston Trade School

1953 Portrait of Bob Duerden at Boston Trade School

The old Boston Trade School building is now part of the Wentworth Institute of Technology.

Bob Meets Marie

Marie Gearin was born on May 28, 1936, at Boston City Hospital. The Gearins lived on Fenwood Road then and later moved to a 26-room Victorian house in Abington that Marie’s father, Joseph Gearin, bought in 1937 for $2500. Marie’s mother, Irene (Maki) Gearin, came from Abington’s Finnish community and Marie is fluent in Finnish to this day. Her father, Joseph Gearin, came from Fenwood Road. Bob and Marie were married in 1973 and they bought their first house in Abington where they lived for 25 years.

Bob Meets Ted

Perhaps no Boston sports figure was more revered than Ted Williams. Growing up in Boston’s 1940s and 1950s was a baseball dreamland. Red Sox names like DiMaggio, Doerr, Pesky and Williams dominated American League sports talk everywhere, while Holmes, Jethro, Sain and Spahn had their own National League following over at Braves Field on Commonwealth Avenue. Very few families had television, so everyone knew Jim Britt and Curt Gowdy, Boston’s popular radio sportscasters.

The New England Sportsman’s Show was an annual event at the Mechanic’s Building at 111 Huntington Avenue, exactly where today’s Prudential Center sits. Exhibition and merchandise booths filled the building’s space where crowds of men roamed about browsing and buying fishing, hunting and camping equipment.

Mechanics Building, Boston, Courtesy Wikipedia The show’s main event was the “tank show”. A huge shallow pool was set up and exhibitions included competitive log rolling by Canadian lumberjacks, canoe tilting, swimming demonstrations, and most famously, fly-fishing demonstrations by Ted Williams. Ted would pierce balloons at the far end of the 70 foot tank with a flick of the wrist sending the graceful swirl of fly-fishing line over the heads of nearby spectators, landing the hook accurately on each target, to pop the row of balloons, one at a time.

Mechanics Building, Boston, Courtesy Wikipedia The show’s main event was the “tank show”. A huge shallow pool was set up and exhibitions included competitive log rolling by Canadian lumberjacks, canoe tilting, swimming demonstrations, and most famously, fly-fishing demonstrations by Ted Williams. Ted would pierce balloons at the far end of the 70 foot tank with a flick of the wrist sending the graceful swirl of fly-fishing line over the heads of nearby spectators, landing the hook accurately on each target, to pop the row of balloons, one at a time.

One of Bob’s friends, Donald Nee, had caught a record striped-bass off Cuttyhunk and it was displayed at the show. Nee invited Bob to come in and meet Ted Williams who stored his fishing gear in Nee’s booth.

Bob came to the hall and found Nee. Soon, Ted Williams, bigger than life, came by and Nee said, “Ted, Bob Duerden here is a Marine.” Ted replied, “Hi. How are ya? What do you do in the Corps?” “I’m an airplane mechanic”, Bob replied. Ted, warming up, says “what kind of planes?” and Bob reported that he worked on F4U-4 Corsair planes, the model Ted flew in WWII. Williams, now fully engaged says “why the hell didn’t you say so,” and thrust out his huge hand for a firm shake. Testing Bob further, he said “What kind of engine is in that plane?” and Bob responded “the Pratt & Whitney R-2800-18W” to which Ted said “Yep, you know your planes.” They then engaged in friendly talk about the Marine Corps and their mutual interest in planes. As their conversation ended, Ted asked Bob if he’d like an autographed photo, and Bob, to his everlasting regret, said no. Bob’s mother never let him forget that terrible lapse in judgement.

Ted Williams, USMC and Boston Red Sox

Ted Williams, USMC and Boston Red Sox

F4U-4 Corsair

F4U-4 Corsair

Bob Goes to Work

Bob can’t remember a time when he didn’t work or wasn’t hustling for a dollar. Back in the day, it wasn’t “work ethic” or greed that drove young people; it was necessity. Any way you could help sustain yourself meant less drain on the family finances which, in most cases, were never robust. With one or more of his pals: Ralph and Larry Chislett, Richie Ogilvie, Bill and Paul Clancy, Ray “Buster” Bradley, Kenny Pineau, and others, Bob built up quite a resume!

Bob shined shoes, delivered food orders at the A&P, and learned the art of “soda jerk”. He set up pins at the alleys in Hyde Square, learned “short order cooking” at a local diner, and was the paper boy to the Haffenreffer brewery office on Germania Street. He was for a very short time an undertaker’s assistant, as well as an unpaid “volunteer” at the Ladder 10 firehouse now occupied by the JP Licks ice cream store. He sold Christmas trees, sold students’ five-cent streetcar tickets, shoveled snow for the City, filled jelly donuts at the local donut shop and on Sunday mornings he delivered much needed medicinal alcohol to needy, hung-over customers of the local drugstore. He was also an independent fireworks distributor as mentioned later on.

Later, Bob became a part-time police officer in Abington, where he got to know the members of the small force there and some of the difficulties even small-town lawmen encounter.

Two of his early jobs are memorable. The worst job he ever had was refilling customers’ mattresses at the Roxbury Mattress Company at 121 Lamartine Street. The other was more interesting as he and two friends were hired to fill injection molding machines at the Flagg Doll Company at 91 Boylston Street. They all got fired for horseplay and moved on. The Flagg dolls, however, are now collectibles from another relatively unknown company, joining automobile, airplane, baseball, radio and other long-forgotten Jamaica Plain industries.

Product packaging of the Flagg Doll Company located at 91 Boylston Street One of the people he met in his early work life as a paper boy became an important part of his later life. The Hickock Newspaper Agency at 95 Boylston Street was sold to a fun-loving Boston policeman, Bill Clancy, of 21a Spring Park Avenue. Bob and Bill became lifelong friends and Officer Clancy served as Bob and Marie’s Best Man. Bob loves to show his friends in Arizona the famous Germania Street address he knew so well on the Sam Adams beers they enjoy so much in Arizona. Bob’s lifetime work was at the Boston Gas Company where he worked for 41 years. That career overlapped his Marine Corps Reserves service of 33 years.

Product packaging of the Flagg Doll Company located at 91 Boylston Street One of the people he met in his early work life as a paper boy became an important part of his later life. The Hickock Newspaper Agency at 95 Boylston Street was sold to a fun-loving Boston policeman, Bill Clancy, of 21a Spring Park Avenue. Bob and Bill became lifelong friends and Officer Clancy served as Bob and Marie’s Best Man. Bob loves to show his friends in Arizona the famous Germania Street address he knew so well on the Sam Adams beers they enjoy so much in Arizona. Bob’s lifetime work was at the Boston Gas Company where he worked for 41 years. That career overlapped his Marine Corps Reserves service of 33 years.

The Boston Gas Company

Now part of National Grid, the British gas and electric utility conglomerate, Boston Gas Company’s operations center was formerly on McBride Street. It was said, probably with some tongue-in-cheek truth, that the immigrant ships from Ireland didn’t head for Ellis Island, but for Boston where a Boston Gas Company truck met them and delivered new laborers to McBride Street.

Bob started at the company in 1957 where he worked in the Service Department. In 1986 he became the Chief Dispatcher – Emergency Services and worked nights at the Rivermoor Street facility in West Roxbury. As such, he dealt with many of the outside street crews and thus developed a finely tuned ear for the various brogues of the company’s diggers.

In a true and fortuitous “small world” incident, Bob reports that when on active duty as an aviation mechanic in 1959 at the Cecil Field Naval Air Station in Florida, a young naval officer came to him and asked to borrow a nose-wheel jack for an A-4 Skyhawk attack jet. Each party recognized a Boston accent and the loan was done with a pleasant exchange of Boston small talk. The young officer, John Bacon, came from Hull.

Years later, Bob met the officer again at the Boston Gas Company where Bacon was a “cadet” in the company’s management training program. Bob kidded the trainee about the loaned wheel jack never being returned (in fact it had been.) They became fast friends and Bacon, who would rise to Presidency of the Boston Gas Company, promised Bob help anytime he needed something. In fact, when Bob was called back to Marine Corps active duty, President Bacon granted Bob a one year leave of absence. Bob fondly recalls how Mr. Bacon always made a point of often sitting with the workers in the cafeteria and not always with the managers.

Bob remembers Gas Company employees getting coffee at Woody’s Variety store at 110 McBride Street. Woodrow “Woody” Barbour lived above the store, and he loved to chat with the Gas Company folks. It was said that long before Woody’s time, the house had been a McBride Street prohibition-era speakeasy.

Bob retired from the Gas Company on April 1, 1998 after a fulfilling career of 41 years.

Robert Duerden, USMC

In November, 1953, Bob took his Marine Corps oath in the Marine Corps administration building at Squantum Naval Air Station in Quincy. Being under-aged at 17, attorney Jim Hennigan on Centre Street had notarized his parents’ approval.

Joining the Marines fulfilled a lifelong ambition that started when he and his father were heading to the Waldorf Restaurant on Summer Street, after a couple of hours at a Boston movie and they encountered two impressive young uniformed men who took notice of the six-year old boy. “Who are they?” he asked his Dad. “Marines,” replied his father, and from then on Bob was determined to become a Marine.

After boot camp, Bob took aircraft mechanic’s training at Cherry Point, North Carolina, and then was assigned to Fighter Squadron VMF-217 at Squantum, in Quincy, Massachusetts. That assignment is memorialized on his present Arizona license plate, VMF-217.

Squantum Naval Air Station has an interesting history. It had originally been the site of a small private air field owned by the Harvard Aeronautical Society who leased the land in 1910 from the New York, New Haven Hartford Railroad. Among other things, the first intercollegiate Glider Meet was held there in 1911. Tragedy struck in 1912 when noted aviatrix, Harriet Quimby and co-pilot William Willard fell to their deaths out of their open plane with thousands of spectators looking on.

Squantum Naval Air Station,Courtesy of Paul Freeman

Squantum Naval Air Station,Courtesy of Paul Freeman

“Abandoned & Little Known Airfields”

http://www.airfields-freeman.com/ During WWI the Navy housed seaplanes there and began training pilots and aircraft mechanics. The air station was closed in 1917 and leased to the Bethlehem Steel Company’s Victory Shipyard which built 35 destroyers there from 1918-1920.

In 1941 an expanded and improved facility was upgraded to a full-fledged Naval Air Station providing combat-ready training and operational security protecting the Boston Harbor waters from German submarines.

In 1942 the small Dennison Airport nearby was annexed to Squantum. Dennison had been founded in 1927 by a group including Amelia Earhart, who flew there. It housed private blimps, hangers, two landing areas and administrative and shop buildings on 27 acres.

Amelia Earhart, Courtesy Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection

Amelia Earhart, Courtesy Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection Dennison Airport , courtesy of Paul Freeman

Dennison Airport , courtesy of Paul Freeman

“Abandoned & Little Known Airfields”

http://www.airfields-freeman.com/ By 1945 Squantum had expanded to 593 acres but in 1953 the base had to be closed due to airspace conflicts with Boston’s Logan Airport. The site was sold and has had much significant development including a prime-location marina and luxury condos.

Years later Bob and his wife returned to Squantum only to find that Marine Administration building where he had taken his Marine oath, had just burned down. They found solace, however, in a nice plate of fried clams on Wollaston Boulevard.

When Squantum was demobilized, Bob was reassigned to South Weymouth Naval Air Station. South Weymouth was originally laid out in 1938 as a proposed municipal airport. In 1942 it became a 1,256 acre Navy blimp base with two huge hangers, roughly 1,000 x 300 feet each, for blimps and aircraft. After WWII, it became a Naval Aircraft Parking Station and was used to store surplus planes. It was deactivated in 1949 and then reactivated again in 1953 to absorb the Navy and Marine air functions from Squantum. In 1997, after years of military readiness, exciting air-shows, and serving as a duty station for many Navy and Marine airmen, the station was closed. It is now owned by the town of Weymouth.

Bob retired from the Marine Corps in 1985 with 33 years of service and the rank of Master Gunnery Sergeant.

Robert Duerden, USMC and Boston Gas Company Jamaica Plain Icons Remembered

Robert Duerden, USMC and Boston Gas Company Jamaica Plain Icons Remembered

A boy’s first car is certainly memorable. One of Bob’s Danforth Street neighbors was a Boston firefighter who owned a 1935 Buick with jump seats. Jump seats, found in limousines and large older cars, were rearward facing, fold-up seats. The firefighter provided car service to undertakers for funerals. He sold the car in 1951 to Bob for $50. Bob was soon traveling to Connecticut and loading-up fireworks for resale back in Boston. He made enough to pay for the car and insurance!

Curtis Hall and the “tank,” or swimming pool, were regular attractions. For two cents, Leo, the attendant in the little ticket booth at the entrance sold you a bar of soap and a dishtowel size “towel”. Swimmers had to first shower in the endless hot shower and then have their feet checked before entering the pool. Boys’ and girls’ days at the tank alternated. On boys’ day, no bathing suits were worn, while on girls’ day a wool suit was issued to the girls. Following their swim, the Danforth Street boys would head for another icon, Brigham’s Ice Cream shop, just a few hundred yards away. Bob still remembers the strong chlorine odor of the tank and the delicious ice cream at Brigham’s.

Bob remembers the “Jakie,” or Jamaica Theatre, at 413 Centre Street, near Hyde Square, as being much more elegant than the Madison Theatre at 292 Centre Street, across from Plant’s Shoe Factory. The Madison was known as the “spit box,” or “madhouse.” The “Jakie” cost 15-cents and a box of popcorn was five-cents so a respectable date would only cost a quarter.

At the Hyde Square streetcar loop, Bob remembers the old green “bubbler,” or drinking fountain, on the sidewalk outside the wall around the House of the Angel Guardian Industrial School, now the site of the Angell Animal Medical Center. The “HAG” as it was known, was run by the Brothers of Charity and it was the threatened life-sentence for any Jamaica Plain boy who didn’t shape up. During the summer, a city crew would come by each day and place blocks of ice to cool the pipes feeding the bubbler.

City drinking fountain, photograph courtesy of Michael Galvin Doyle’s Café, at 3484 Washington Street, often took some of Bob’s early Gas Company earnings. He remembers the long-serving Boston City Councilor, Albert Leo “Dapper” O’Neil, occasionally buying a round at Doyle’s always-busy tavern.

City drinking fountain, photograph courtesy of Michael Galvin Doyle’s Café, at 3484 Washington Street, often took some of Bob’s early Gas Company earnings. He remembers the long-serving Boston City Councilor, Albert Leo “Dapper” O’Neil, occasionally buying a round at Doyle’s always-busy tavern.

Hanlon’s shoe store, above the C. B. Rogers’ drugstore at 701 Centre Street, was widely known and under Ed Hanlon’s son-in-law, underwent a major expansion into the suburbs. While working for the Boston Gas Company Bob remembers a service call in Abington where he found the customer to be Mr. Ed Hanlon and they had a nice chat. The photograph of Mr. Hanlon fitting new shoes to the famous vaudevillian, Jimmy Durante, is an icon itself.

Ed Hanlon fits Jimmy Durante for a new pair of shoes Bob remembers renting horses, with a friend, at the William Wright Riding School at 104 Williams Street, and then trying to get the horses to follow the bridle path up to Franklin Park. The horses, however, had different ideas and were completely uncontrollable under the reins of the two wannabe cowboys. The police from Station 13 were alerted to the two prancing horses on Forest Hills Street and upon arrival, the cops ordered the boys to dismount and walk the animals back to the stable.

Ed Hanlon fits Jimmy Durante for a new pair of shoes Bob remembers renting horses, with a friend, at the William Wright Riding School at 104 Williams Street, and then trying to get the horses to follow the bridle path up to Franklin Park. The horses, however, had different ideas and were completely uncontrollable under the reins of the two wannabe cowboys. The police from Station 13 were alerted to the two prancing horses on Forest Hills Street and upon arrival, the cops ordered the boys to dismount and walk the animals back to the stable.

Life in Arizona

Bob and Marie love Arizona. Their retirement in Green Valley, AZ, has been wonderful in a new house they built when their first house, inherited from Marie’s mother, proved to be too small. They had planned to retire in Abington, but after several visits and one military deployment to Arizona they came to unanimous agreement one evening to move to Arizona.

They enjoy their community’s amenities along with the wonderful weather. Bob is neither a hunter nor a golfer so he volunteers to patrol the University of Arizona’s experimental soil and air quality range of 80 square miles within Green Valley. Once or twice a week he and a friend drive out there looking for trash, stray cattle, or seldom-seen border crossers.

The Duerdens enjoy good health and Bob believes his is partly related to sleeping in an unheated bedroom at 39 Danforth Street many years ago. With that good health they have been able to satisfy long postponed travel plans by visiting Thailand, China, Russia, Italy, Ireland, a Rhine River cruise, a Tahiti cruise to the Society and Cook Islands and a 27 day cruise from South Africa to Ft. Lauderdale.

Bob and Marie at a pub in Dingle, County Kerry, Ireland When asked to look back for his fondest memory of Jamaica Plain, Bob replied, “My friends on Danforth and Lamartine Streets and the things we did together.” A beautifully simple statement about living a great childhood in a very special place.

Bob and Marie at a pub in Dingle, County Kerry, Ireland When asked to look back for his fondest memory of Jamaica Plain, Bob replied, “My friends on Danforth and Lamartine Streets and the things we did together.” A beautifully simple statement about living a great childhood in a very special place.

Bromley Park, the Origin of the Name by Richard Heath

Bromley Park was a 680-foot long residential square set perpendicular to Bickford Street and dead ended at the old Boston and Providence Railroad right of way. The street was lined with brick bow fronted row houses and divided by three rectangular strips planted with trees, grass and shrubs exactly like those town house blocks built in the South End such as Rutland Square, Worcester Square and Braddock Park. Bromley Street and Albert Street came off Bromley Park at right angles and connected it to Heath Street. The Bromley Park playground, 50 - 60 Bickford Street and 950 to 954 Parker Street occupy what was Bromley Park for 75 years.

Bromley Park has a more significant history which is forgotten today and obscure a half century ago: it was the country house of the venerable Lowell family. All of Bromley Park Houses was the 18th and 19th century estate of Judge John Lowell, his son and grandson. Another son, Francis Cabot Lowell, brought the industrial revolution to America when he built the first integrated cotton mill on the banks of the Charles River in Waltham in 1813. This enterprise was expanded into the great mill town on the banks of the Merrimack River in 1823 named Lowell in his honor. On March 10, 1785, Judge John Lowell bought a 10 1/2 half-acre farm and farm house which fronted on Center Street for 750 pounds. (Suffolk deeds. Book 147. Page 269). Center Street - known then as The Great Road to Dedham and Providence - was one of the principle thoroughfares through Roxbury. The house stood about where 267 Center Street is today. In the 17th century the land was originally owned by and John Weld, one of the founding families - and one of the richest landowners - of Roxbury. (Note: until 1851 Jamaica Plain was a part of Roxbury; called Jamaica end of the town of Roxbury as early as 1667). The Weld planting fields adjoined the farm of William Heath - another founding family - which stretched up against Parker Hill.

The Lowells were not one of the founding families of Boston or Roxbury but settled on the North Shore at Cape Ann after they arrived in Boston on June 23, 1639. The patriarch, Percival Lowell, described as a "solid citizen of Bristol", determined at the age of 68 that the future was in the New World. A man of wealth, he left England in April, 1639 with a party of 16 people: his two sons John and Richard and their wives, servants, furniture and livestock.

Governor John Winthrop needed solid dependable people to settle the North Shore area as a buffer against the French from Canada and he urged that the Lowells remove to Newburyport. It was there that Judge John Lowell was born in 1743. His father was the pastor of the Third Parish Church of Newburyport. After graduating from Harvard like his father, Judge Lowell clerked at a Boston law firm for three years before opening his own office in Newburyport with two of the richest merchants in that town as his chief clients. His wealth was such that at the age of thirty he built twin houses on High Street in Newburyport which were among the finest in the port. His contemporary and colleague, the future president John Adams, wrote jealously to his wife that Lowell has "a palace like a noble man and lives a life of great splendor."

It was out of the chaos of the revolutionary war that the Lowell family emerged as a family of enormous wealth and influence in Massachusetts and established them among the highest of the Brahmin class. Judge Lowell was by inheritance, temperament and the society in which he lived and worked a Loyalist type. But he was a shrewd man and like his forebear Percival was alert to the fact that the New World had greater things in store than the monarchy of England. So although he knew the last two Royal governors personally, he threw his fortunes in with that of the nascent nation and joined the political arm of the nationalists, the Committee of Safety as an elected Selectman from Newburyport. On March 7, 1776 British General Lord William Howe abandoned Boston and removed to Halifax, Nova Scotia taking with him many of the most distinguished families in Boston who left behind large empty houses on corner lots filled with gardens and orchards. Judge John Lowell moved into one of those houses, the former home of John Amory at the end of 1776. The Amory House was at the corner of Tremont and Beacon Street opposite King's Chapel. A peach orchard grew in the spacious grounds which stimulated Lowell's interest in agriculture.

Lowell seized the opportunity left by the fleeing Loyalists by filling the void they left behind. The capital was almost empty of attorneys and Lowell prospered as legal advisor to the State Commissioners responsible for Tory property seized by authorization of the 1779 Confiscation Act. This closely followed the Banishment Act of 1778 which ordered all those who sided with the King to leave the Commonwealth. Lowell drew up deeds of sale and arranged leases and auctions of the properties. The sale of Loyalist properties and leases of others - such as the Amory House which Lowell rented from the Commonwealth - helped pay for the costs of the Revolutionary War. But he made most of his fortune during the war years in managing the legal work on captured ships and commerce seized by privateers from the British. In 1782, Congress appointed him Judge of Appeal for admiralty cases. After the war, he worked as the executor and estate administrator for numerous Tory emigres such as the former Royal Governor Hutchinson whom he knew personally.

Lowell also represented Commodore Joshua Loring whose Jamaica Plain mansion stills stands on Center Street, as well as the Vassal, Lechmere and Coffin families and others living in London and Bristol. (Loyalists from Salem moved to Bristol). Lowell handled all their affairs in America and for comfortable fees regularly sent substantial sums from the sale of property and income from estates across the Atlantic.

Judge Lowell took great interest in the growth of Boston. If his contemporary John Adams worked on the national level, John Lowell worked to strengthen Boston and Massachusetts in the years after the Revolutionary War. In 1783, Lowell was one of the founding directors of the First National Bank of Boston (His son John would be one of the first vice presidents of the Provident Institute for Savings in 1817). He invested in shares in bridges, canals and toll roads.

Judge Lowell also worked to improve the state of agriculture left in shambles after a decade of warfare. He was an avid gentleman farmer and one of the members of what Tamara Thornton describes in her book Cultivating Gentlemen ( New Haven, 1989), as the Boston Federalist agricultural society who preferred to live in country seats in the manner of British gentry.

After he moved to Roxbury he commuted across the Boston Neck to his law office but mostly he conducted his business on the farm. And for good reason. Writing in his 1946 biography of the Lowell family (The Lowells and Their Seven Worlds from which much of this history is taken), Ferris Greenslet described the Lowell estate just above Hoggs Bridge where Center Street crossed Stony Brook: "In the old Judge's time and that of his son, it must have been retired and lovely. To the north across the short pitched valley of Stony Brook, the steep acclivity of Parker Hill hid the spires and soft- coal smoke of Boston. Towards the sunset stretched the shaded hills and bowery hollows of Brookline. The old Judge taking his hundred steps on a sunny morning could see the bright waters of Boston and Dorchester Bays." Another reason why Judge Lowell enjoyed the estate - and probably why he bought it - was that it was owned 90 years earlier by Joseph Gardener whose family also had deep roots in Salem.

Joseph Gardner was a member of the small but very wealthy Brookline wing of the Gardner family. Like the Lowells they were originally from Salem. The family began with Thomas Gardener (1592 - 1674) who was probably born in Scotland but moved to Dorsetshire, England. In 1624, Thomas Gardner landed at what is today Gloucester Harbor to manage a fishery plantation established by a group of investors from Dorchester, England. About five years before the Pilgrims landed, merchants from the south of England had sent fishing vessels to the shores of New England. This was a long trip and the catch often spoiled so it was decided to build a fishing plantation at Cape Ann where the fish could be caught in season and preserved before returning to English markets. But the rocky coast proved unsuitable and the venture failed. Gardner stayed on and with Roger Conant built a permanent settlement at Naumkeag or what is today called Salem about 1626. Gardner was made a freeman of the Church on May 17,1637 two years before Percival Lowell arrived. Thomas Gardner's two sons - both of whom were born in England - were Thomas and Peter. They each married Roxbury women and as each received land as part of the marriage, the brothers removed there to begin a second branch of the family (Until 1705 Brookline was a part of Roxbury called Muddy River).

Peter Gardner was born in England in 1617 and joined his father at Salem in 1635. On May 9, 1646 he married Rebecca Crooke (or Cooke) and their son Joseph was born on Jan 11, 1759. Peter Gardner lived in Roxbury at the junction of Warren and Dudley Streets where he had a garden and nursery. For many years in the 17th and into the first decade of the 18th century what is today known as Dudley Square was called Gardner's Green.

His brother Thomas settled in Brookline and by 1674 owned 175 acres of farmland over what is today Leverett Pond, Pill Hill, Cypress Street and Route 9. He became the richest landowner in the Muddy River section of Roxbury. On March 22, 1682 Joseph married Mary Weld daughter of John Weld, one of the most famous of the great Roxbury families. They settled on land owned by her father on the Great Road to Dedham. The house in which Judge Lowell lived was probably built by Joseph Gardner about the time of his marriage. John Weld had a house in the town center and a another on South Street in what is today the Arnold Arboretum. Weld used the Dedham Road land as income by renting it to a tenant farmer. All property owners whose land was located on a main thoroughfare of Roxbury incurred certain public responsibilities: by order of the town selectmen, all property along the road had to be fenced and those fences kept in good condition; any large rocks in the public way along a property owner's land had to be removed and no private owner could remove or damage a tree on the public wayside.