Prohibition Killed a Coffee Tree on McBride Street

–But It Made a Surprising Recovery

By Peter O’Brien, February, 2010

A Grand Opening

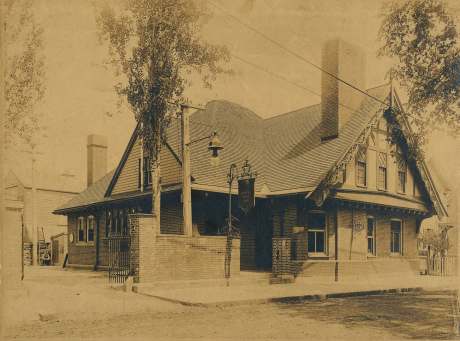

On June 29, 1898, three well-known Boston beer and ale brewers opened a handsome new Inn at 16 Keyes Street, Jamaica Plain. The owners, Bradley & Farmer, Rueter & Co., and A.J. Houghton & Co. called it the Coffee Tree Inn, naming it for a coffee tree that once grew on the site.

Keyes Street Re-named McBride Street

Keyes Street was laid out in 1850 and named for John Keyes who was a local tanner, making leather from animal hides.

David Greenough developed the land he had bought from the Loring estate that included Keyes Street. Greenough proposed 50-foot lots on Keyes Street for sale to the Irish immigrants flooding into the area to work as laborers and domestics in the burgeoning Jamaica Plain economy. Thus, the area became known as “Little Ireland.” Later, growth of the Boston Gas Company, further down Keyes Street, brought even more Irish labor and tavern customers to the area.

In 1921, several Jamaica Plain streets, squares and playgrounds were renamed to honor World War I heroes who had been killed in that war. Keyes Street was renamed for Corporal John J. McBride who was born on Keyes Street and had been killed in France.

The Coffee Tree

A coffee tree growing on McBride Street would strike anyone who ever tried to grow tomatoes there as an astonishing horticultural achievement. However, there is a coffee tree, unrelated to the tropical coffee plant that produces our morning coffee, native to the eastern and central United States. A member of the bean or legume family, the Kentucky Coffeetree (Gymnocladus dioicus) produces a bean which early settlers in Kentucky used to make a bitter, low-grade coffee substitute. It is a fairly common, large deciduous tree with about twenty specimens presently growing in the Arnold Arboretum, one of which dates to 1873, planted just a year after the Arboretum opened. Another labeled specimen is presently growing along the sidewalk near the tennis courts just east of the Shattuck Hospital. A Kentucky Coffeetree could grow in Massachusetts but how did one find its way to McBride Street?

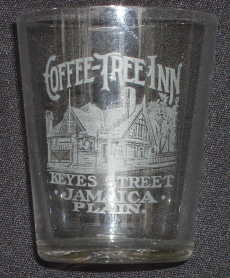

Whether the owners knew or cared how it got there, the tree became the logo for the Inn and it can be seen on the Inn’s sign. Although not documented, the tree logo was also used in an approximately five-foot diameter tile mosaic in the floor of the main room of the Inn. A long-time Jamaica Plain resident, Mrs. Constance (Cuddy) Buckley, clearly remembers this mosaic before it was covered with machinery in the building’s later life. In that later life the new owners also remembered the tile mosaic in the floor.

The Inn

The Inn was designed by Boston architect J. William Beal. Mr. Henry A. Rueter suggested its conceptual design based on his survey of popular English and German taverns. Rueter, who owned the Highland Spring Brewery in Roxbury, was President of the United States Brewers’ Association. His estate was on the Jamaicaway where Jamaica Towers is presently located. Rueter and the other owners apparently felt that while the final design of the building might not blend with the neighborhood’s modest architecture, the Inn’s European Tudor design elements would resonate with the large and growing immigrant population in Jamaica Plain, especially those living and traveling on McBride Street.

The Inn’s design called for dark red burned brick for the first floor with typical Tudor style half-timbered and stuccoed walls above. A beautifully decorated gable was painted in deep green. The overhanging eaves were trimmed with relief-carved bargeboards in a sinuous stylized grapevine pattern. A carved finial at the peak faced the street.

An elegant cast iron sign, illuminated by an early electric arc light, hung near the walled-in entrance to the Inn. Another cast iron sign advertising Sterling Ale was mounted to the front of the building near the square entrance porch.  Cast iron gates secured the driveway that was flanked by birch trees and led from the un-paved McBride Street to the rear delivery area. One can imagine the delivery wagon with its stacked cases or kegs of beer navigating between the brick columns supporting the gates. Rounded granite bumper blocks protected the bases of the columns. These blocks were important architectural features in the horse drawn wagon era with its iron-rimmed wheels. They became less important later when motor trucks with rubber tires could more accurately navigate the opening.

Cast iron gates secured the driveway that was flanked by birch trees and led from the un-paved McBride Street to the rear delivery area. One can imagine the delivery wagon with its stacked cases or kegs of beer navigating between the brick columns supporting the gates. Rounded granite bumper blocks protected the bases of the columns. These blocks were important architectural features in the horse drawn wagon era with its iron-rimmed wheels. They became less important later when motor trucks with rubber tires could more accurately navigate the opening.

The diamond pane leaded windows reinforced the Tudor design concept. Beautiful stained glass windows with English and Germanic heraldic emblems graced the side of the building facing the driveway. The stained glass windows remained long after the Inn was closed and the later owners of the building remember them well.

The footprint of the main room in the Inn was about 40 feet square, with carved oak paneling all around and an oak bar on three sides. A tall oak screen separating the bar from the dining area with its oak tables afforded privacy for diners. Customers could enjoy a slice of prime Westphalian ham with roasted potatoes and a mug of beer or ale in comparative privacy.

High above the bar a skylight admitted soft diffused light. The presence of the two light poles in the picture indicates that the Inn was electrified at some point. At night the glow of early electric lighting fixtures would then have illuminated the room.

A great fireplace of red sandstone stood just beside the entrance door. It can be located more precisely from the location of the massive (front) chimney in the steeply pitched roof. It must have been very pleasant with a crackling fire burning on a snowy winter’s night with a mix of brogues and other dialects engaged in lively conversation.

Signs were carved in the oak panels at the base of the skylight dome. One stated: “Enough Is Good Use - Too Much Is Abuse.”

Bartenders

One profession that kept many men working in the early 20th century was bartending. It was a respected profession and bartender’s reputations and skills were widely known and discussed. The ability to keep a bar well stocked, clean, and properly serviced were the attributes of a good bartender. Keeping the beer pipes from the kegs below to the bar above cleaned out regularly and the floor covered with fresh sawdust were other measures of a barkeep’s performance. He also had to keep peace in the establishment and be sure over-drinking patrons were sent home before becoming inebriated, a state the Irish would quite naturally minimize as; “heyadafewinim,” (he had a few in him.) And, above all, the attentive bartender had to manage the “cuff,” his record of charged drinks recorded on his starched shirt cuff.

Thanks to the famous Doyle’s Café, founded 1882 and still going strong, we have a copy of an old Doyle’s menu that carried an undated song by M.C. Hanney. It named the many local Jamaica Plain barrooms and their bartenders and their attributes noted in each location. One verse mentions the Coffee Tree Inn:

“Then take a walk up Keyes Street, and you cannot fail to see

An ancient looking bar room, ‘tis called The Coffee Tree

They say that Bradley runs the place, when Mike Brady is not there

Mike’s Irish wit and pleasant ways, are always rich and rare … .” And thanks to another long-time Jamaica Plain resident, Michael Galvin, we have a picture of a genuine shot glass from The Coffee Tree Inn. Michael also allowed us to copy his beautiful Reuter’s Highland Spring Brewery sign. Michael’s eclectic collection of JP memorabilia includes one of the green cast iron water bubblers used around the corner from the Inn on South Street and two working gas street lights from nearby Boynton Street that were serviced morning and night by our local lamplighter, Mr. Shields, “who made the night a little brighter wherever he would go.”

And thanks to another long-time Jamaica Plain resident, Michael Galvin, we have a picture of a genuine shot glass from The Coffee Tree Inn. Michael also allowed us to copy his beautiful Reuter’s Highland Spring Brewery sign. Michael’s eclectic collection of JP memorabilia includes one of the green cast iron water bubblers used around the corner from the Inn on South Street and two working gas street lights from nearby Boynton Street that were serviced morning and night by our local lamplighter, Mr. Shields, “who made the night a little brighter wherever he would go.”

Neighbors and Customers

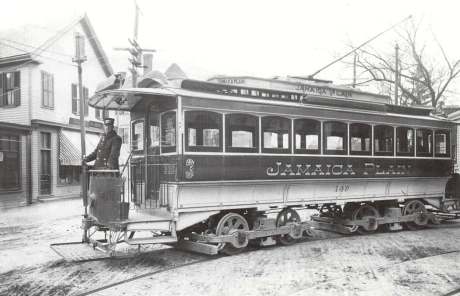

The Inn was located a few hundred yards from the Jamaica Plain streetcar car barns on South Street. The car barns site became the Jamaica Plain Loop after the barns were torn down in the 1930s; and 25 years later a public housing project was built there.

Among its clientele, the Inn probably served members of the Hampstead Club that was located on the second floor at 114a South Street at the corner of McBride and South Streets. In later years, Wilson’s meat market occupied the first floor at that address, and later still, the Ristuccia family (Bob’s Spa) bought the building. That building, on the corner of McBride Street, can be seen with the large striped awning behind the motorman in the photo of an 1898 streetcar leaving the South Street car barns.

A short way up South Street, one of the green cast iron water bubblers, a copy of which resides in Michael Galvin’s garden, quenched summer thirsts.

A short way up South Street, one of the green cast iron water bubblers, a copy of which resides in Michael Galvin’s garden, quenched summer thirsts.

Another neighbor of the Coffee Tree Inn would have been the blacksmith shop, next door at 10 McBride Street. Ignatius J. Craffey founded the shop about 1910 and operated it until about 1925. John P. Mahoney, who formerly owned stables and a smithy at 716 Centre Street, took over and ran it until James ‘Jimmy’ Lovett bought it. Jimmy had arrived from Ballyferriter, County Kerry, Ireland in 1928, just a year after he witnessed Lindbergh’s historic flight over Ireland heading for Paris. Jimmy bought the shop from Mahoney’s widow in the mid 1930s and ran it until about 1961. Earlier the former stable at the front of the structure was removed, leaving only the small smithy shop at the rear of the lot.

Jimmy’s son, John Lovett, learned the trade and worked there as a youngster, helping his dad shoeing a diminishing horse population. Thus, John Lovett is probably the last resident farrier (blacksmith) in Jamaica Plain.  John LovettThe rhythmic pealing of Jimmy Lovett’s hammer on his anvil with streamers of hot sparks flying was our own version of the Blacksmith Blues long before that song hit No. 3 on the charts in 1952! It’s sad and so often true that we didn’t appreciate what colorful additions things like Lovett’s blacksmith shop and our lamplighter, Mr. Shields, made to our lives and neighborhood until much, much later. It’s especially true to those of us who took Forging (blacksmithing, not writing bad checks) at Mechanic Arts High School in Boston back then.

John LovettThe rhythmic pealing of Jimmy Lovett’s hammer on his anvil with streamers of hot sparks flying was our own version of the Blacksmith Blues long before that song hit No. 3 on the charts in 1952! It’s sad and so often true that we didn’t appreciate what colorful additions things like Lovett’s blacksmith shop and our lamplighter, Mr. Shields, made to our lives and neighborhood until much, much later. It’s especially true to those of us who took Forging (blacksmithing, not writing bad checks) at Mechanic Arts High School in Boston back then.

Prohibition Arrives

The Inn prospered until the Volstead Act, commonly called Prohibition, ended the country’s legal supply of alcoholic beverages in 1920. The Inn was then vacant for six years except that in 1924 a Daniel J. Hogan briefly appears as proprietor of the Coffee Tree Inn. Was Hogan attempting a comeback as a dry restaurant, or did he suspect early repeal of Prohibition? In any case, Prohibition, a well intentioned but failed experiment to control excessive drinking, was finally repealed in 1933

A New Life for the Building

In 1926, Joseph Yerkes (aka Joe Bags) of Brunswick Street, Roxbury, started the Washington Wet Wash, a commercial and residential wet wash laundry in the unoccupied Inn building. “Wet wash,” meant that your laundry was washed, but not dried. Later, Harry and Israel Yerkes joined their brother Joe as partners in the laundry enterprise. When Joe died, his wife, Betty, remarried a man named Kaplan and they lived in Brookline. The laundry was then in Betty’s name for a while. About 1951, Joe’s daughter, Helen Reinstein, and her husband Mel, took over operation of the laundry.

Many of our moms and neighbors worked at the laundry at one time or another. It was very heavy and hot work so turnover was high. One of the things that probably hastened the laundry’s demise was the overnight laundry service that was offered to stimulate business. Laundry picked up the night before would be delivered, in a repainted deep green hearse, early next morning! That door-to-door service went the way of all other home delivered things like bakery goods, diapers, twice-a-day mail delivery, milk, ice, fruit, vegetables and peddler’s wares as the age of the automobile arrived.

The Reinsteins, now of Delray Beach, Florida, remember the hearse, the tile mosaic, the stained glass windows and the fireplace in the building but little else of its fifty-year old well worn architectural features because they were busy trying to earn a living; not cataloguing the building’s formerly handsome details. They do, however, remember many of the local “characters” and tradesmen that worked there including the local bookie. The bookie already had a dedicated ‘private’ phone booth in Bob’s Spa around the corner at 128 South Street. Nevertheless this enterprising bookmaker wanted to put an “office” upstairs in the laundry, but Joe Yerkes, sensing potential problems in that arrangement wisely declined.

As the economy was improving, unskilled help was becoming hard to find and retain at the McBride Street location so in 1966 the laundry was moved to 830 Blue Hill Avenue as the Jamaica Plain Laundry and Dry Cleaners. It continued there until Oct 4, 1972 when it was finally closed.

The Inn is Demolished

It isn’t clear when the Inn/Wet Wash building was demolished or who owned it at the time.

The land is now owned by James’s Gate Pub and together with Lovett’s blacksmith shop’s land; the two abutting parcels form the present paved parking lot for the pub.

James’s Gate is located on the former site of Hester’s Tavern, irreverently known for years as “the chapel”, at 5 McBride Street, located across the street from the former Inn. In later lives, as times improved, Hester’s was elevated to “the cathedral” with little increase in either reverence or maintenance.

Bernard T. “Bonnie” Hester, a former bricklayer from Dalrymple Street, opened his tavern at 5 McBride Street in the mid-1930s and ran it until 1959 when it became McBride Lunch. Around 1967 it was called Joe Cunniff’s Bar. Cunniff was a long-time patron and former bartender. Thereafter it was Danny Harold’s, Dory Lounge, MacDonald’s and 5 McBride Lunch again until James’s Gate purchased and renovated the property in 1997.

James’s Gate’s extensive renovations with antique building materials replicated an Irish pub alongside a contemporary dining room in a building inspired by the St. James’s Gate Brewery in Dublin, home of Guinness Stout since 1759.

The Tradition Continues

So, 112 years after the Grand Opening of the Coffee Tree Inn, with the caveat that “Enough is Good Use - Too Much is Abuse,” the tradition of good food and drink for travelers and the residents of Little Ireland lives on in a nifty Irish pub on McBride Street.

And while the Inn, the blacksmith and the lamplighter are long gone, the memories of them, and of a great growing up in Jamaica Plain, are refreshed whenever we play their songs in our heads.

Sources and References

Boston Globe, June 30, 1898 and April 18, 1921

Doyle’s Café Menu (undated)

Remember Jamaica Plain? by Mark Bulger

JP Memorabilia by Michael “Mikey” Galvin

Song: The Blacksmith Blues by Jack Holmes, 1952

Song: The Old Lamplighter by Nat Simon and Charles Tobias, 1946

Frank Norton archives

James’s Gate Restaurant and Pub website

Special Thanks to John Lovett, Mrs. Constance (Cuddy) Buckley, Frank Ratta, James McNally, Paul Byrne, Anne (Hester) Devaney, Ira Yerkes, Mel and Helen Reinstein, Maggie Redfern, Arnold Arboretum, Visitor Education Assistant, and Diane Parks and Liane Lalor at the Boston Public Library, Central Library.