“And finally, what is your fondest memory of growing up in Jamaica Plain? Pause… My friends on Danforth and Lamartine Streets and the things we did together.”

From a March 11, 2015 interview with former resident, Robert Duerden, of Green Valley, Arizona. A career Marine and long-time Boston Gas employee, Bob Duerden’s Jamaica Plain is unique but he shares the same experience of many growing up in a very special place.

By Peter O’Brien, March, 2015

Bob’s Beginnings

Robert F. Duerden was born on February 6, 1936, at Boston City Hospital, as it was known then. It’s now called Boston Medical Center. His father, Ralph E. Duerden, came from Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, and had worked as a steward on the old Boston to Yarmouth Ferry when it was an overnight cruise. His mother, Mary (Long), grew up on Lawn Street in Roxbury; called by many who lived there, “the sunny side” of Mission Hill.

Bob’s sister, Carole (Duerden) Lee, of Millis, was also born at Boston City Hospital and was named after the beautiful movie star, Carole Lombard, whom their mother loved.

The Duerdens lived at 39 Danforth Street in a four-room, cold-water flat in a two-decker. There was neither hot water, nor central heat. An old black cast-iron kerosene stove served for heating and cooking in the kitchen, while the parlor was warmed by a small kerosene heater. Bob remembers bed-time buried under several blankets and laying perfectly still until his body warmed the sheets. In the morning, a coat of “fern” frost covered the inside of the bedroom windows. Years later, Bob’s remarkably good health was thought to be related to his hardy tolerance of the cold winter nights in Jamaica Plain.

Duerden home at 39 Danforth Street Their next-door neighbor, at 43 Danforth, was Al Wittenauer’s garage. Al was the Duerden’s landlord and a no-nonsense German whose cigar smoke still lingers in Bob’s memory.

Duerden home at 39 Danforth Street Their next-door neighbor, at 43 Danforth, was Al Wittenauer’s garage. Al was the Duerden’s landlord and a no-nonsense German whose cigar smoke still lingers in Bob’s memory.

Next to Al’s garage, at 45 Danforth, was the well-known Boylston Schul-Verein German Club. The club has since moved to Walpole, Massachusetts but the Danforth Street building is still there housing Spontaneous Celebrations, a community arts center. During WWII, the FBI closed the club a couple of times as spies were being seen everywhere and both German and Japanese Americans felt the government’s scrutiny and harassment.

Boylston Schul-Verein German Club at 45 Danforth Street Working Parents

Boylston Schul-Verein German Club at 45 Danforth Street Working Parents

Bob’s dad, Ralph Duerden, worked 39 years in the shipping department at Salada Tea in Boston. This Boston location was once the company’s U.S. headquarters. Salada’s 12-foot high bronze doors, installed in 1927 at 330 Stuart Street, are among Boston’s many attractions. Depicted on the doors is the harvesting of tea in Ceylon and shipment of it to the west.

Salada Building bronze doors: Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones collection

Salada Building bronze doors: Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones collection Salada Building bronze doors: Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones collection One of Bob’s proudest memories of his dad was when he was home on Marine Corps leave about 1955. His dad asked Bob if he would wear his uniform and accompany him to the streetcar stop opposite the A&P Store on Centre Street where for years he commuted to work. He told Bob how proud he was of him and wanted to introduce his new Marine to his fellow riders on the streetcar. Bob of course said yes and spit-shined his shoes, polished his brass insignia and pressed his new “tropicals” uniform to razor sharp creases. While still only a PFC and with only a Marksmanship badge, the Marine uniform made any young man look like a recruiting poster!

Salada Building bronze doors: Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones collection One of Bob’s proudest memories of his dad was when he was home on Marine Corps leave about 1955. His dad asked Bob if he would wear his uniform and accompany him to the streetcar stop opposite the A&P Store on Centre Street where for years he commuted to work. He told Bob how proud he was of him and wanted to introduce his new Marine to his fellow riders on the streetcar. Bob of course said yes and spit-shined his shoes, polished his brass insignia and pressed his new “tropicals” uniform to razor sharp creases. While still only a PFC and with only a Marksmanship badge, the Marine uniform made any young man look like a recruiting poster!

At 6:00 am the next morning they walked to the streetcar stop and his dad proudly introduced him to his fellow commuters. The streetcar came and Bob decided to board it with his dad who introduced him to the conductor who refused to let Bob pay the fare. (The conductor was his mother’s uncle!) At the Salada building he met many more employees including the President of the company, a Mr. Thacker. Bob was never more proud of his dad and vice versa. Bob’s father passed in 1963 and Bob has never forgotten the compassion shown to his dad by the Salada Tea Company.

Bob’s mother, Mary, had a really fun job. She worked the hot-dog stand behind home plate at Fenway Park! She loved baseball, and for years scored the games in a home-made, spiral-bound, notebook lined out for the game’s roster to record each batter’s performance in true score-keeping notation. She became an expert on the Sox and could recite many milestones, including their 1918 World Series games. She was said to know more about baseball than everyone on their street combined. Sadly, when she passed at age 93, the years’ of homemade Red Sox box-scores could not be found.

Bob remembers his mother sitting on the stoop as several Red Sox players walked by the house on the way to the German Club which was then a very popular nightspot. Joe Cronin, former Red Sox player and later Manager, stopped one day and said “hey, I know you” remembering her from Fenway’s hot-dog stand. Thereafter, he would always stop and chat with her about baseball and the Red Sox.

Joe Cronin, Boston Red Sox Education

Joe Cronin, Boston Red Sox Education

Bob attended the Chestnut Avenue School for K-2, and the Wyman School for 3rd and 4th grade, followed by the Lowell School for 7th and 8th grade, and then on to the Mary E. Curley School for 9th grade.

He then attended Boston Technical High School, formerly known as Mechanics Arts, located at Belvidere and Dalton Streets in Boston, where the present Hilton and Sheraton hotels are located. After two days under teacher/coach, William “Dutchie” Holland, Bob decided Boston Trade School would be a better fit. He went to Trade seeking a transfer and found a sympathetic assistant principal, Mr. Murphy from Mission Hill, who said he could only find room for him in the Electrical course.

Boston Trade School was one of the several Boston high schools that taught useful trades including printing, woodworking, forging (blacksmithing), pattern making, electrical work, machine shop, and automotive repair on an alternating weekly basis; i.e. a week in the shop followed by a week in the classroom.

Many a young man went on to a productive life’s work with the skills learned at Boston Trade School. In Bob’s case, the electrical training helped him immensely in his Marine aircraft maintenance job. He says his time at Boston Trade was a life-changing experience.

Bob graduated in 1953 and remembers his “one-button-roll” suit bought for the event at the fine Callahan’s men’s clothing store at 362c Centre Street, at the corner of Forbes Street.

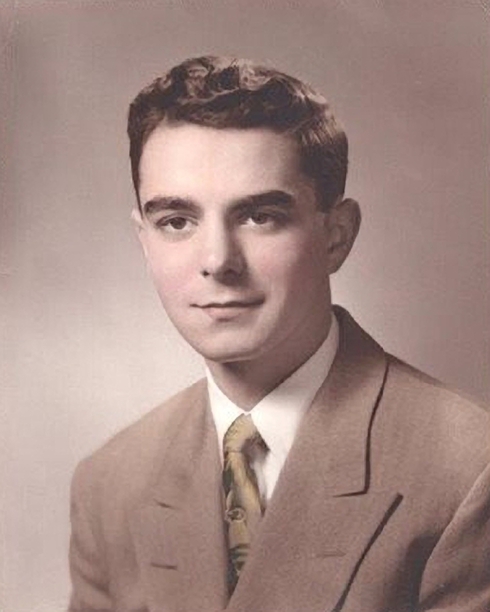

1953 Portrait of Bob Duerden at Boston Trade School

1953 Portrait of Bob Duerden at Boston Trade School

The old Boston Trade School building is now part of the Wentworth Institute of Technology.

Bob Meets Marie

Marie Gearin was born on May 28, 1936, at Boston City Hospital. The Gearins lived on Fenwood Road then and later moved to a 26-room Victorian house in Abington that Marie’s father, Joseph Gearin, bought in 1937 for $2500. Marie’s mother, Irene (Maki) Gearin, came from Abington’s Finnish community and Marie is fluent in Finnish to this day. Her father, Joseph Gearin, came from Fenwood Road. Bob and Marie were married in 1973 and they bought their first house in Abington where they lived for 25 years.

Bob Meets Ted

Perhaps no Boston sports figure was more revered than Ted Williams. Growing up in Boston’s 1940s and 1950s was a baseball dreamland. Red Sox names like DiMaggio, Doerr, Pesky and Williams dominated American League sports talk everywhere, while Holmes, Jethro, Sain and Spahn had their own National League following over at Braves Field on Commonwealth Avenue. Very few families had television, so everyone knew Jim Britt and Curt Gowdy, Boston’s popular radio sportscasters.

The New England Sportsman’s Show was an annual event at the Mechanic’s Building at 111 Huntington Avenue, exactly where today’s Prudential Center sits. Exhibition and merchandise booths filled the building’s space where crowds of men roamed about browsing and buying fishing, hunting and camping equipment.

Mechanics Building, Boston, Courtesy Wikipedia The show’s main event was the “tank show”. A huge shallow pool was set up and exhibitions included competitive log rolling by Canadian lumberjacks, canoe tilting, swimming demonstrations, and most famously, fly-fishing demonstrations by Ted Williams. Ted would pierce balloons at the far end of the 70 foot tank with a flick of the wrist sending the graceful swirl of fly-fishing line over the heads of nearby spectators, landing the hook accurately on each target, to pop the row of balloons, one at a time.

Mechanics Building, Boston, Courtesy Wikipedia The show’s main event was the “tank show”. A huge shallow pool was set up and exhibitions included competitive log rolling by Canadian lumberjacks, canoe tilting, swimming demonstrations, and most famously, fly-fishing demonstrations by Ted Williams. Ted would pierce balloons at the far end of the 70 foot tank with a flick of the wrist sending the graceful swirl of fly-fishing line over the heads of nearby spectators, landing the hook accurately on each target, to pop the row of balloons, one at a time.

One of Bob’s friends, Donald Nee, had caught a record striped-bass off Cuttyhunk and it was displayed at the show. Nee invited Bob to come in and meet Ted Williams who stored his fishing gear in Nee’s booth.

Bob came to the hall and found Nee. Soon, Ted Williams, bigger than life, came by and Nee said, “Ted, Bob Duerden here is a Marine.” Ted replied, “Hi. How are ya? What do you do in the Corps?” “I’m an airplane mechanic”, Bob replied. Ted, warming up, says “what kind of planes?” and Bob reported that he worked on F4U-4 Corsair planes, the model Ted flew in WWII. Williams, now fully engaged says “why the hell didn’t you say so,” and thrust out his huge hand for a firm shake. Testing Bob further, he said “What kind of engine is in that plane?” and Bob responded “the Pratt & Whitney R-2800-18W” to which Ted said “Yep, you know your planes.” They then engaged in friendly talk about the Marine Corps and their mutual interest in planes. As their conversation ended, Ted asked Bob if he’d like an autographed photo, and Bob, to his everlasting regret, said no. Bob’s mother never let him forget that terrible lapse in judgement.

Ted Williams, USMC and Boston Red Sox

Ted Williams, USMC and Boston Red Sox

F4U-4 Corsair

F4U-4 Corsair

Bob Goes to Work

Bob can’t remember a time when he didn’t work or wasn’t hustling for a dollar. Back in the day, it wasn’t “work ethic” or greed that drove young people; it was necessity. Any way you could help sustain yourself meant less drain on the family finances which, in most cases, were never robust. With one or more of his pals: Ralph and Larry Chislett, Richie Ogilvie, Bill and Paul Clancy, Ray “Buster” Bradley, Kenny Pineau, and others, Bob built up quite a resume!

Bob shined shoes, delivered food orders at the A&P, and learned the art of “soda jerk”. He set up pins at the alleys in Hyde Square, learned “short order cooking” at a local diner, and was the paper boy to the Haffenreffer brewery office on Germania Street. He was for a very short time an undertaker’s assistant, as well as an unpaid “volunteer” at the Ladder 10 firehouse now occupied by the JP Licks ice cream store. He sold Christmas trees, sold students’ five-cent streetcar tickets, shoveled snow for the City, filled jelly donuts at the local donut shop and on Sunday mornings he delivered much needed medicinal alcohol to needy, hung-over customers of the local drugstore. He was also an independent fireworks distributor as mentioned later on.

Later, Bob became a part-time police officer in Abington, where he got to know the members of the small force there and some of the difficulties even small-town lawmen encounter.

Two of his early jobs are memorable. The worst job he ever had was refilling customers’ mattresses at the Roxbury Mattress Company at 121 Lamartine Street. The other was more interesting as he and two friends were hired to fill injection molding machines at the Flagg Doll Company at 91 Boylston Street. They all got fired for horseplay and moved on. The Flagg dolls, however, are now collectibles from another relatively unknown company, joining automobile, airplane, baseball, radio and other long-forgotten Jamaica Plain industries.

Product packaging of the Flagg Doll Company located at 91 Boylston Street One of the people he met in his early work life as a paper boy became an important part of his later life. The Hickock Newspaper Agency at 95 Boylston Street was sold to a fun-loving Boston policeman, Bill Clancy, of 21a Spring Park Avenue. Bob and Bill became lifelong friends and Officer Clancy served as Bob and Marie’s Best Man. Bob loves to show his friends in Arizona the famous Germania Street address he knew so well on the Sam Adams beers they enjoy so much in Arizona. Bob’s lifetime work was at the Boston Gas Company where he worked for 41 years. That career overlapped his Marine Corps Reserves service of 33 years.

Product packaging of the Flagg Doll Company located at 91 Boylston Street One of the people he met in his early work life as a paper boy became an important part of his later life. The Hickock Newspaper Agency at 95 Boylston Street was sold to a fun-loving Boston policeman, Bill Clancy, of 21a Spring Park Avenue. Bob and Bill became lifelong friends and Officer Clancy served as Bob and Marie’s Best Man. Bob loves to show his friends in Arizona the famous Germania Street address he knew so well on the Sam Adams beers they enjoy so much in Arizona. Bob’s lifetime work was at the Boston Gas Company where he worked for 41 years. That career overlapped his Marine Corps Reserves service of 33 years.

The Boston Gas Company

Now part of National Grid, the British gas and electric utility conglomerate, Boston Gas Company’s operations center was formerly on McBride Street. It was said, probably with some tongue-in-cheek truth, that the immigrant ships from Ireland didn’t head for Ellis Island, but for Boston where a Boston Gas Company truck met them and delivered new laborers to McBride Street.

Bob started at the company in 1957 where he worked in the Service Department. In 1986 he became the Chief Dispatcher – Emergency Services and worked nights at the Rivermoor Street facility in West Roxbury. As such, he dealt with many of the outside street crews and thus developed a finely tuned ear for the various brogues of the company’s diggers.

In a true and fortuitous “small world” incident, Bob reports that when on active duty as an aviation mechanic in 1959 at the Cecil Field Naval Air Station in Florida, a young naval officer came to him and asked to borrow a nose-wheel jack for an A-4 Skyhawk attack jet. Each party recognized a Boston accent and the loan was done with a pleasant exchange of Boston small talk. The young officer, John Bacon, came from Hull.

Years later, Bob met the officer again at the Boston Gas Company where Bacon was a “cadet” in the company’s management training program. Bob kidded the trainee about the loaned wheel jack never being returned (in fact it had been.) They became fast friends and Bacon, who would rise to Presidency of the Boston Gas Company, promised Bob help anytime he needed something. In fact, when Bob was called back to Marine Corps active duty, President Bacon granted Bob a one year leave of absence. Bob fondly recalls how Mr. Bacon always made a point of often sitting with the workers in the cafeteria and not always with the managers.

Bob remembers Gas Company employees getting coffee at Woody’s Variety store at 110 McBride Street. Woodrow “Woody” Barbour lived above the store, and he loved to chat with the Gas Company folks. It was said that long before Woody’s time, the house had been a McBride Street prohibition-era speakeasy.

Bob retired from the Gas Company on April 1, 1998 after a fulfilling career of 41 years.

Robert Duerden, USMC

In November, 1953, Bob took his Marine Corps oath in the Marine Corps administration building at Squantum Naval Air Station in Quincy. Being under-aged at 17, attorney Jim Hennigan on Centre Street had notarized his parents’ approval.

Joining the Marines fulfilled a lifelong ambition that started when he and his father were heading to the Waldorf Restaurant on Summer Street, after a couple of hours at a Boston movie and they encountered two impressive young uniformed men who took notice of the six-year old boy. “Who are they?” he asked his Dad. “Marines,” replied his father, and from then on Bob was determined to become a Marine.

After boot camp, Bob took aircraft mechanic’s training at Cherry Point, North Carolina, and then was assigned to Fighter Squadron VMF-217 at Squantum, in Quincy, Massachusetts. That assignment is memorialized on his present Arizona license plate, VMF-217.

Squantum Naval Air Station has an interesting history. It had originally been the site of a small private air field owned by the Harvard Aeronautical Society who leased the land in 1910 from the New York, New Haven Hartford Railroad. Among other things, the first intercollegiate Glider Meet was held there in 1911. Tragedy struck in 1912 when noted aviatrix, Harriet Quimby and co-pilot William Willard fell to their deaths out of their open plane with thousands of spectators looking on.

Squantum Naval Air Station,Courtesy of Paul Freeman

Squantum Naval Air Station,Courtesy of Paul Freeman

“Abandoned & Little Known Airfields”

http://www.airfields-freeman.com/ During WWI the Navy housed seaplanes there and began training pilots and aircraft mechanics. The air station was closed in 1917 and leased to the Bethlehem Steel Company’s Victory Shipyard which built 35 destroyers there from 1918-1920.

In 1941 an expanded and improved facility was upgraded to a full-fledged Naval Air Station providing combat-ready training and operational security protecting the Boston Harbor waters from German submarines.

In 1942 the small Dennison Airport nearby was annexed to Squantum. Dennison had been founded in 1927 by a group including Amelia Earhart, who flew there. It housed private blimps, hangers, two landing areas and administrative and shop buildings on 27 acres.

Amelia Earhart, Courtesy Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection

Amelia Earhart, Courtesy Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection Dennison Airport , courtesy of Paul Freeman

Dennison Airport , courtesy of Paul Freeman

“Abandoned & Little Known Airfields”

http://www.airfields-freeman.com/ By 1945 Squantum had expanded to 593 acres but in 1953 the base had to be closed due to airspace conflicts with Boston’s Logan Airport. The site was sold and has had much significant development including a prime-location marina and luxury condos.

Years later Bob and his wife returned to Squantum only to find that Marine Administration building where he had taken his Marine oath, had just burned down. They found solace, however, in a nice plate of fried clams on Wollaston Boulevard.

When Squantum was demobilized, Bob was reassigned to South Weymouth Naval Air Station. South Weymouth was originally laid out in 1938 as a proposed municipal airport. In 1942 it became a 1,256 acre Navy blimp base with two huge hangers, roughly 1,000 x 300 feet each, for blimps and aircraft. After WWII, it became a Naval Aircraft Parking Station and was used to store surplus planes. It was deactivated in 1949 and then reactivated again in 1953 to absorb the Navy and Marine air functions from Squantum. In 1997, after years of military readiness, exciting air-shows, and serving as a duty station for many Navy and Marine airmen, the station was closed. It is now owned by the town of Weymouth.

Bob retired from the Marine Corps in 1985 with 33 years of service and the rank of Master Gunnery Sergeant.

Robert Duerden, USMC and Boston Gas Company Jamaica Plain Icons Remembered

Robert Duerden, USMC and Boston Gas Company Jamaica Plain Icons Remembered

A boy’s first car is certainly memorable. One of Bob’s Danforth Street neighbors was a Boston firefighter who owned a 1935 Buick with jump seats. Jump seats, found in limousines and large older cars, were rearward facing, fold-up seats. The firefighter provided car service to undertakers for funerals. He sold the car in 1951 to Bob for $50. Bob was soon traveling to Connecticut and loading-up fireworks for resale back in Boston. He made enough to pay for the car and insurance!

Curtis Hall and the “tank,” or swimming pool, were regular attractions. For two cents, Leo, the attendant in the little ticket booth at the entrance sold you a bar of soap and a dishtowel size “towel”. Swimmers had to first shower in the endless hot shower and then have their feet checked before entering the pool. Boys’ and girls’ days at the tank alternated. On boys’ day, no bathing suits were worn, while on girls’ day a wool suit was issued to the girls. Following their swim, the Danforth Street boys would head for another icon, Brigham’s Ice Cream shop, just a few hundred yards away. Bob still remembers the strong chlorine odor of the tank and the delicious ice cream at Brigham’s.

Bob remembers the “Jakie,” or Jamaica Theatre, at 413 Centre Street, near Hyde Square, as being much more elegant than the Madison Theatre at 292 Centre Street, across from Plant’s Shoe Factory. The Madison was known as the “spit box,” or “madhouse.” The “Jakie” cost 15-cents and a box of popcorn was five-cents so a respectable date would only cost a quarter.

At the Hyde Square streetcar loop, Bob remembers the old green “bubbler,” or drinking fountain, on the sidewalk outside the wall around the House of the Angel Guardian Industrial School, now the site of the Angell Animal Medical Center. The “HAG” as it was known, was run by the Brothers of Charity and it was the threatened life-sentence for any Jamaica Plain boy who didn’t shape up. During the summer, a city crew would come by each day and place blocks of ice to cool the pipes feeding the bubbler.

City drinking fountain, photograph courtesy of Michael Galvin Doyle’s Café, at 3484 Washington Street, often took some of Bob’s early Gas Company earnings. He remembers the long-serving Boston City Councilor, Albert Leo “Dapper” O’Neil, occasionally buying a round at Doyle’s always-busy tavern.

City drinking fountain, photograph courtesy of Michael Galvin Doyle’s Café, at 3484 Washington Street, often took some of Bob’s early Gas Company earnings. He remembers the long-serving Boston City Councilor, Albert Leo “Dapper” O’Neil, occasionally buying a round at Doyle’s always-busy tavern.

Hanlon’s shoe store, above the C. B. Rogers’ drugstore at 701 Centre Street, was widely known and under Ed Hanlon’s son-in-law, underwent a major expansion into the suburbs. While working for the Boston Gas Company Bob remembers a service call in Abington where he found the customer to be Mr. Ed Hanlon and they had a nice chat. The photograph of Mr. Hanlon fitting new shoes to the famous vaudevillian, Jimmy Durante, is an icon itself.

Ed Hanlon fits Jimmy Durante for a new pair of shoes Bob remembers renting horses, with a friend, at the William Wright Riding School at 104 Williams Street, and then trying to get the horses to follow the bridle path up to Franklin Park. The horses, however, had different ideas and were completely uncontrollable under the reins of the two wannabe cowboys. The police from Station 13 were alerted to the two prancing horses on Forest Hills Street and upon arrival, the cops ordered the boys to dismount and walk the animals back to the stable.

Ed Hanlon fits Jimmy Durante for a new pair of shoes Bob remembers renting horses, with a friend, at the William Wright Riding School at 104 Williams Street, and then trying to get the horses to follow the bridle path up to Franklin Park. The horses, however, had different ideas and were completely uncontrollable under the reins of the two wannabe cowboys. The police from Station 13 were alerted to the two prancing horses on Forest Hills Street and upon arrival, the cops ordered the boys to dismount and walk the animals back to the stable.

Life in Arizona

Bob and Marie love Arizona. Their retirement in Green Valley, AZ, has been wonderful in a new house they built when their first house, inherited from Marie’s mother, proved to be too small. They had planned to retire in Abington, but after several visits and one military deployment to Arizona they came to unanimous agreement one evening to move to Arizona.

They enjoy their community’s amenities along with the wonderful weather. Bob is neither a hunter nor a golfer so he volunteers to patrol the University of Arizona’s experimental soil and air quality range of 80 square miles within Green Valley. Once or twice a week he and a friend drive out there looking for trash, stray cattle, or seldom-seen border crossers.

The Duerdens enjoy good health and Bob believes his is partly related to sleeping in an unheated bedroom at 39 Danforth Street many years ago. With that good health they have been able to satisfy long postponed travel plans by visiting Thailand, China, Russia, Italy, Ireland, a Rhine River cruise, a Tahiti cruise to the Society and Cook Islands and a 27 day cruise from South Africa to Ft. Lauderdale.

Bob and Marie at a pub in Dingle, County Kerry, Ireland When asked to look back for his fondest memory of Jamaica Plain, Bob replied, “My friends on Danforth and Lamartine Streets and the things we did together.” A beautifully simple statement about living a great childhood in a very special place.

Bob and Marie at a pub in Dingle, County Kerry, Ireland When asked to look back for his fondest memory of Jamaica Plain, Bob replied, “My friends on Danforth and Lamartine Streets and the things we did together.” A beautifully simple statement about living a great childhood in a very special place.